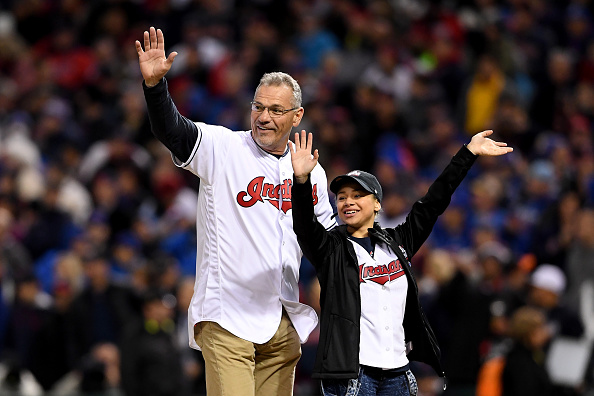

In 1980, rookie Indians left fielder Joe Charboneau took Northeast Ohio by storm, opening beer bottles with his eye sockets or forearm, hitting 23 homers, inspiring a hit song, and winning the AL Rookie of the Year Award with 73 percent of the vote. By 1983, the player fans called “Super Joe” was out of the league, undone by injuries, better known as a cautionary tale than as a ballplayer. Injuries did him in: after multiple back surgeries, he just couldn’t hit any more:

| Joe Charboneau: 1980- ’82 | ||||||||

| Year | G | PA | HR | RBI | AVG | OBP | SLG | WAR |

| 1980 | 131 | 512 | 23 | 87 | .289 | .358 | .488 | 2.4 |

| 1981 | 48 | 147 | 4 | 18 | .210 | .247 | .362 | -0.3 |

| 1982 | 22 | 63 | 2 | 9 | .214 | .286 | .393 | -0.3 |

He may be the most famous flameout in baseball history; he played a total of 70 games after winning his award but he is far from the only player to suffer the “flame out” fate.

For the purposes of this article, I’m looking at players who had a terrific rookie year and then really never did much of anything else after.

A decade ago, Steve Treder took a much broader look at players who “were driving Pepsi trucks,” who played at a very high value and then saw their production fall off all at once. In particular, I looked at players who enjoyed notable rookie seasons. Either they hit at least 25 home runs, or they collected at least 2.5 bWAR. I used bWAR as a criterion because I was searching the baseball-reference Play Index. The WAR totals reported in the tables below are Fangraphs WAR. Then I looked at all players who finished with career bWAR between 2 and 8, and I did a VLOOKUP on the two groups. This yielded a set of players who started strong but didn’t do much for the rest of their careers.

Some of these players had two good seasons before their production tumbled. This was the case for two Chicago pitchers, Randy Wells and Jason Bere; it was also true for All-Star Yankee second baseman Jerry Coleman, who later made the Hall of Fame as a broadcaster. Other players had even harder-to-describe career paths, like Ron Kittle and Eric Hinske, both of whom won the Rookie of the Year award, experienced major sophomore slumps and eventually lost their starting jobs, but hung around long enough to become effective part-time players.

Unfortunately, this methodology makes it hard to come up with an exact number of Joe Charboneaus in baseball history. I tried my best and here are the results:

- Harry Byrd, right-handed pitcher: He was Rookie of the Year in 1952 and led the league in losses in 1953. Those were his only 200-inning seasons.

- F.P. Santangelo and Chris Singleton, outfielders: These two contemporaries finished fourth and sixth in the Rookie of the Year voting in the late 1990s, collecting more than 2,000 plate appearances as glove-first outfielders.

- Gene Bearden, left-handed pitcher: Another Indian, led his league in ERA, finished eighth in the rookie vote in 1948, and famously started and won that season’s one-game playoff against the Red Sox on one day’s rest. For the rest of his career, he totaled 558.1 innings with a 4.55 ERA.

Perhaps the best exemplar of this one-and-done career path, even more than Super Joe himself, is Billy Grabarkewitz. After a cup of coffee in 1969, Grabarkewitz proved himself an invaluable Dodgers utility player in 1970, playing 156 games at second, third and shortstop, displaying solid defense and a terrific stick, especially considering that he played his home games in Chavez Ravine: 17 home runs, 84 RBI, and a .289/.399/.454 triple slash in 640 plate appearances. He was an All-Star that year.

For the rest of his seven-year career, he logged 680 plate appearances and 11 homers. He was out of the major leagues before he turned 30:

| BILLY GRABARKEWITZ, 1969-1975 |

|---|

| Year | G | PA | HR | RBI | AVG | OBP | SLG | WAR |

| 1969 | 34 | 70 | 0 | 5 | .092 | .145 | .138 | -0.8 |

| 1970 | 156 | 640 | 17 | 84 | .289 | .399 | .454 | 6.1 |

| 1971 | 44 | 90 | 0 | 6 | .225 | .389 | .296 | 0.8 |

| 1972 | 53 | 166 | 4 | 16 | .167 | .265 | .278 | -0.7 |

| 1973 | 86 | 238 | 5 | 16 | .205 | .343 | .333 | 0.3 |

| 1974 | 87 | 184 | 2 | 14 | .226 | .339 | .310 | 0.2 |

| 1975 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | .000 | .000 | .000 | -0.2 |

Just as it had been with Super Joe, injuries completely sapped his ability. “Baseball was easy for me when I was healthy,” he told Fred Claire, the former general manager of the Dodgers. “But when I broke my ankle in the minor leagues and then tore up my shoulder in spring training, I was never the same player.”

Mitchell Page’s problems were more personal. He was sensational as a rookie left fielder in 1977, and though he finished second in the Rookie of the Year voting to 21-year-old DH Eddie Murray, Page had the far better year at the plate and in the field. He hit .307/.405/.521 in the spacious Oakland Coliseum, with 21 homers and 42 stolen bases.

That season yielded a 28.0 power-speed number. Created by Bill James, PSN is a good way of measuring players who are both fast and powerful: it’s the harmonic mean of home runs and stolen bases, or 2 x (HR x SB)/(HR + SB). That year, Page had the second-highest power-speed number in all of baseball, behind only Bobby Bonds. (Page’s 1977 season is tied for 152nd place on the all-time power-speed list. Of the 151 seasons above him, 19 were posted by a Bonds.)

Though future Hall of Famers Andre Dawson and Eddie Murray won the Rookie of the Year awards in 1977, Page was almost certainly the best rookie in baseball that year ; his 6.2 WAR nearly lapped the field. The next season, he was a shadow of his former self. His defense was markedly worse, and while his bat was still effective it was not nearly as explosive as it had been. In all, he only produced 1.9 WAR that year. And that was the last year he would be even adequate. In the final six seasons of his career, he played 381 games, collected 1,227 plate appearances, and was worth -0.9 WAR.

| MITCHELL PAGE, 1977-1984 |

|---|

| Year | G | PA | HR | RBI | AVG | OBP | SLG | WAR |

| 1977 | 145 | 592 | 21 | 75 | .307 | .405 | .521 | 6.2 |

| 1978 | 147 | 579 | 17 | 70 | .285 | .355 | .459 | 1.9 |

| 1979 | 133 | 539 | 9 | 42 | .247 | .323 | .335 | -1.1 |

| 1980 | 110 | 393 | 17 | 51 | .244 | .311 | .443 | 0.6 |

| 1981 | 34 | 101 | 4 | 13 | .141 | .200 | .283 | -0.7 |

| 1982 | 31 | 87 | 4 | 7 | .256 | .333 | .474 | 0.2 |

| 1983 | 57 | 92 | 0 | 1 | .241 | .341 | .278 | -0.1 |

| 1984 | 16 | 15 | 0 | 0 | .333 | .467 | .417 | 0.2 |

It is not entirely clear exactly what caused his fall, but there may have been a number of contributing factors. He did have injuries, and he was one of many, many players who had run-ins with A’s owner Charlie Finley, getting suspended during spring training in 1979 after asking for a raise. Some of his success in 1977 may have been naturally unsustainable: that can often be the case when a 25-year old posts a career-high .343 BABIP during his rookie year. And his fielding wasn’t great to begin with. His teammates nicknamed him “Radar,” former Athletics equipment manager Steve Vucinich told the Oakland Tribune, because “he needed radar to catch a fly ball.” That may have been due to his eyes. “His eyesight would trouble him for the rest of his career,” Steven Goldman writes at Baseball Prospectus, “causing him difficulty in picking up the ball in the outfield, and perhaps at the plate as well.”

After his playing career was over, he spent a number of years in the St. Louis Cardinals organization, and later served as a hitting coach with the Washington Nationals. As Bruce Markusen wrote at Hardball Times, he lost his job with the Cardinals due to drinking problems. Commenters on the piece noted that he had entered Alcoholics Anonymous and was a faithful attendee. He died four years ago at the age of 59.

Rick Ankiel’s story is more recent and probably better known than the others but it’s worth repeating. USA Today named him the High School Player of the Year in 1997. That year, the St. Louis Cardinals drafted him and gave him the highest bonus any high school pitcher had ever received. He blew through the minor leagues, receiving his first cup of coffee in 1999 — when he was still just 19 years old — and was a big leaguer for good in 2000. He pitched brilliantly in the regular season, going 11-7 with a 3.50 ERA and finishing second in the Rookie of the Year voting, leading his team in ERA as the 95-win Cardinals cruised to take the Central Division pennant by 10 games. Then, in October, things got weird.

Pat Jordan described what happened next in The New York Times Magazine:

In two starts and one relief appearance, first against the Braves and then against the Mets, he walked 11 batters in four innings and threw nine wild pitches, most of which sailed 10 feet over the batters’ heads. He broke a record for wild pitches in an inning that had stood since 1890. His once-classic delivery was riddled with the flaws of a Little Leaguer. He looked like a pitcher who, in a single moment, forgot how to pitch.

Of course, Ankiel’s story didn’t end there. A fine hitter as a rookie — he hit .250/.292/.382 with two homers, much better than most 20-year old position players — he struggled through two more unsuccessful years as a pitcher and then remade himself as a full-time outfielder, ultimately starting 345 games in center field, one of the most athletically demanding positions on the diamond. He had only a four-year career as a pitcher, but he had an 11-year career as a major league player, in one of the most incredible career reinventions since that of Babe Ruth.

| RICK ANKIEL AS A PITCHER, 1999-2001, 2004 |

|---|

| Year | G | IP | W-L | ERA | FIP | K/9 | K/BB | WAR |

| 1999 | 9 | 33 | 0-1 | 3.27 | 2.92 | 10.6 | 2.8 | 1.1 |

| 2000 | 31 | 175 | 11-7 | 3.50 | 4.12 | 10.0 | 2.2 | 3.4 |

| 2001 | 6 | 24 | 1-2 | 7.13 | 8.09 | 10.1 | 1.1 | -0.6 |

| 2004 | 5 | 10 | 1-0 | 5.40 | 4.75 | 8.1 | 9.0 | 0 |

| RICK ANKIEL AS AN OUTFIELDER, 2007-2013 |

|---|

| Year | G | PA | HR | RBI | AVG | OBP | SLG | WAR |

| 2007 | 47 | 190 | 11 | 39 | .285 | .328 | .535 | 1.5 |

| 2008 | 120 | 463 | 25 | 71 | .264 | .337 | .506 | 1.7 |

| 2009 | 122 | 404 | 11 | 38 | .231 | .285 | .387 | 0.2 |

| 2010 | 74 | 240 | 6 | 24 | .232 | .321 | .389 | 0.6 |

| 2011 | 122 | 415 | 9 | 37 | .239 | .296 | .363 | 1.2 |

| 2012 | 68 | 171 | 5 | 15 | .228 | .282 | .411 | -0.1 |

| 2013 | 45 | 136 | 7 | 18 | .188 | .235 | .422 | -0.4 |

But what had happened? In the Times piece, Jordan sheds light on Ankiel’s home life. His father, Rick Ankiel Sr., was a Florida drug smuggler who was given a six-year sentence in March 2000, when his son was in spring training before his rookie year. Before that, he was controlling to the point of emotional abusiveness, punishing Ankiel for the slightest mental lapses in games and forcing him to stick with the sport. And Ankiel’s Cardinals coaches were under strict orders not to do anything that could interfere with his natural talent. “When I asked my pitching coaches what I was doing wrong, they wouldn’t say a word to me,” Ankiel told Jordan. “They’d just say, ‘I’m not allowed to mess with you.’”

He pitched fewer than 300 innings in the minors before his rookie season, only 137.2 above A-ball. The 2000 playoffs marked the first time that he had ever failed to succeed. Jordan argues that Ankiel’s psychological struggles were rooted in the fact that neither the overprotective Cardinals nor his overcritical father had done anything to prepare him. His ultimate success as an outfielder came on his terms. As Michael Baumann wrote at the now defunked Grantland, “The sine wave of Ankiel’s career (because “arc” really isn’t the right word in his case) strains the bounds of one’s imagination.”

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!