Each spring, after the last game of the Stanley Cup Final, the Conn Smythe Trophy is awarded to the player who is voted most valuable player for his team in the entire playoffs. The Penguins who have earned the award, a four-tiered square wooden base topped with a silver maple leaf and silver replica of Maple Leaf Gardens, are Mario Lemieux (twice), Evgeni Malkin and Sidney Crosby.

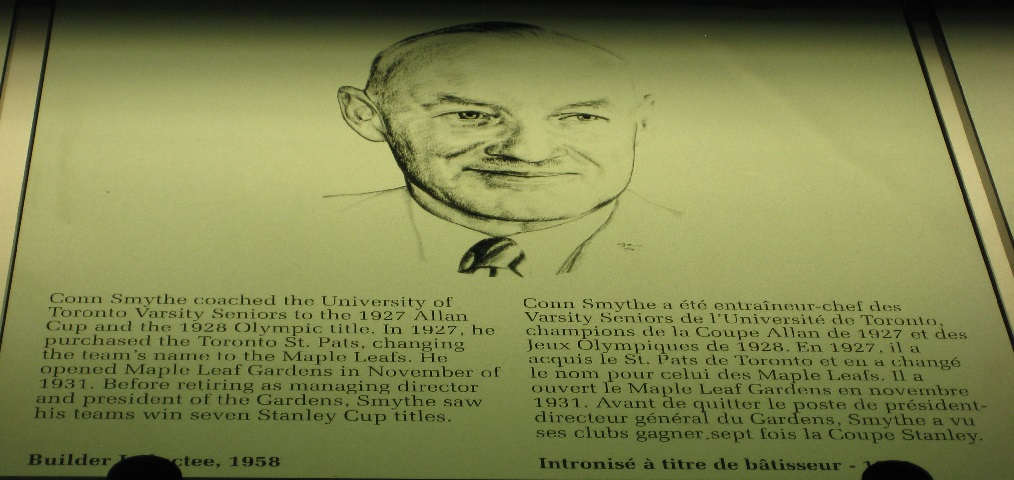

Conn Smythe was chiefly responsible for building the Toronto Maple Leafs in their early years but he also served in both World War I and World War II.

Today, on Veterans Day in the United States and Remembrance Day in Canada, as we pause to honor those who have fought and sacrificed for us, it is a good time to look back at the life of a man who made his mark in hockey and in military service.

Constantine Falkland Cary “Conn” Smythe was born in Toronto in 1895 to a book-obsessed Irish father and an absent, oft-drunk English mother. Mostly due to his father’s inability to hold a steady job or manage money competently, Smythe grew up in poverty and loneliness, constantly moving from house to house as his mother disappeared and reappeared without warning, while his father’s focus was on books, writing and “theosophy”, a quasi-religious movement.

His peers recognized his leadership qualities and Smythe was named captain of the College junior hockey team. He went on to enroll in engineering at University of Toronto where he earned a spot on the hockey team as a freshman. In his sophomore season, he was named junior team captain, scoring 33 goals in 15 games and led his squad to an appearance at the Ontario provincial final. Back in the final round the following year, Smythe scored twice late in the championship-winning game.

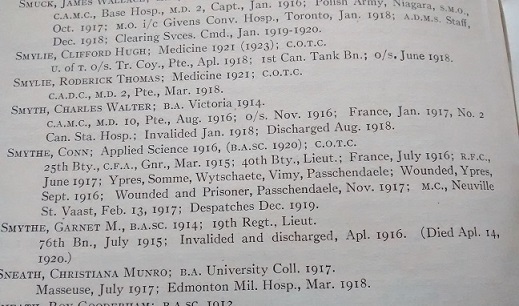

It was the spring of 1915 and World War I was escalating in Europe. Without hesitation, Smythe joined the 40th Battery of the Canadian Field Artillery. After roughly a year of training and waiting, he was sent to England where his battery was deployed to France, then Belgium. At Ypres and the Somme, two of the deadliest battle sites in World War I, Smythe began to see the realities of war up close when his battery traded gunfire with the German army, resulting in the death of his unit’s Major.

Smythe, who was spared the same fate when a comrade sheltered him in a corpse-filled trench, became his battery’s interim commanding officer. As in hockey, Smythe led by example as a soldier, moving heavy horse-drawn guns while constantly facing a barrage of enemy gunfire and shelling. At the battle of Vimy Ridge, a hilltop stronghold controlled by Germany that would later be considered a watershed Canadian military victory, Smythe tirelessly worked to move guns and resupply ammunition. In one instance, he charged up the hillside with only a revolver. He ended up in a trench and shot three German soldiers, earning a Military Cross.

Later, he received air force training and on a mission over Passchendaele, Smythe’s plane was downed by German artillery. He also had been shot in the leg and was captured as a prisoner of war, remaining in German custody until the Armistice to end World War I was signed, November 11, 1918.

Smythe had earned enough money to lift himself out of the poverty he hated so much growing up and became an investor in the Toronto St. Patricks NHL team. More importantly, he became team manager, wisely changing the club’s name to “Maple Leafs” to appeal to all of English Canada, used radio broadcasts of games as a revenue generator and convinced local banks, industry and trade unions to finance the erection of Maple Leaf Gardens in 1931 despite the Great Depression. The arena and club became national institutions as fans flocked to the Gardens, watching the Leafs appear in seven of the next nine Stanley Cup Finals.

By the end of the 1930s, with war looming again, Major Conn Smythe, now in his mid-forties, surprised everyone by re-enlisting in the army – not for ceremonial duties, but to go back to the front lines. He held strong opinions In hockey and in life about loyalty, leadership, bravery and sacrifice so the decision to sign up for military duty again came down to a simple question he asked himself: “Was I a fraud or did I live up to my own principles?”

After Smythe exhorted his players to undergo basic training, the club manager led the 30th Battery of the Royal Canadian Artillery to England in 1942. Two years later, a month after the Allied D-Day invasion, Smythe and his unit approached northern France from a similar route, entrusted with protecting a town near Normandy. The German Luftwaffe constantly attacked and one night, a tarp covering an ammunition truck in Smythe’s area caught on fire. Immediately, Smythe led his men to try to remove the tarp to avert a catastrophic explosion. Unfortunately, the truck exploded and Smythe ended up with shrapnel in his back and one of his legs, rendering him temporarily paralyzed from the waist down.

Returning home once again, Smythe was unafraid to rip the government for what he perceived as a lack of training for soldiers sent overseas. He then transitioned back into his responsibilities with the Maple Leafs, overseeing four Stanley Cup wins in five seasons to close out the 1940s. In 1958, he was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame and in 1965, the award that bears his name was presented for the first time.

Perhaps it is appropriate that the highest individual award given each season honors a man who gave his highest effort at building the sport of hockey and the highest effort in serving during wartime.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!