This postseason feels like it has been dominated by young Aces. With the historically great New York Mets quartet of Matt Harvey, Jacob deGrom, Noah Syndergaard, and Steven Matz, leading the headlines. Those four were followed closely by Marcus Stroman in terms of importance to their teams’ postseason chances. And the Chicago Cubs are handed the ball to a 25 year old Kyle Hendricks down 2-0 in the best of seven NLCS. All of these young guys have made fewer than 60 career regular season starts. Most are effectively in their second year in the Bigs, and all are quite good. This influx of good young pitching (and hitting) has been a topic of conversation for the better part of the last two years, but this number of second year stars playing this late into October got me thinking.

A common theme among those close to the game suggests that young pitchers and hitters develop at the big league level in three distinct stages.

- Excel when they’re first called up

- Struggle as the league develops “a book” or approach to counter what the new guy is doing

- Adjust to what opponents are doing and settle toward true statistical ability.

The summary is to talent evaluators what “regression to the norm” means for stat heads. Baseball certainly does require these constant adjustments, as hitters and pitchers must continue to try to surprise and outperform one another. But I’m wondering just how real that three-staged performance ladder is today. The game is constantly shifting at varying rates. For example, the strike zone shifted has shifted since 2009, but TBS’s broadcast has yet to pick up on the way the strike zone is called in 2015. Luckily, we have a mountain of data available through FanGraphs, baseball-reference.com, and other sites through which to either back up or refute baseball dictums.

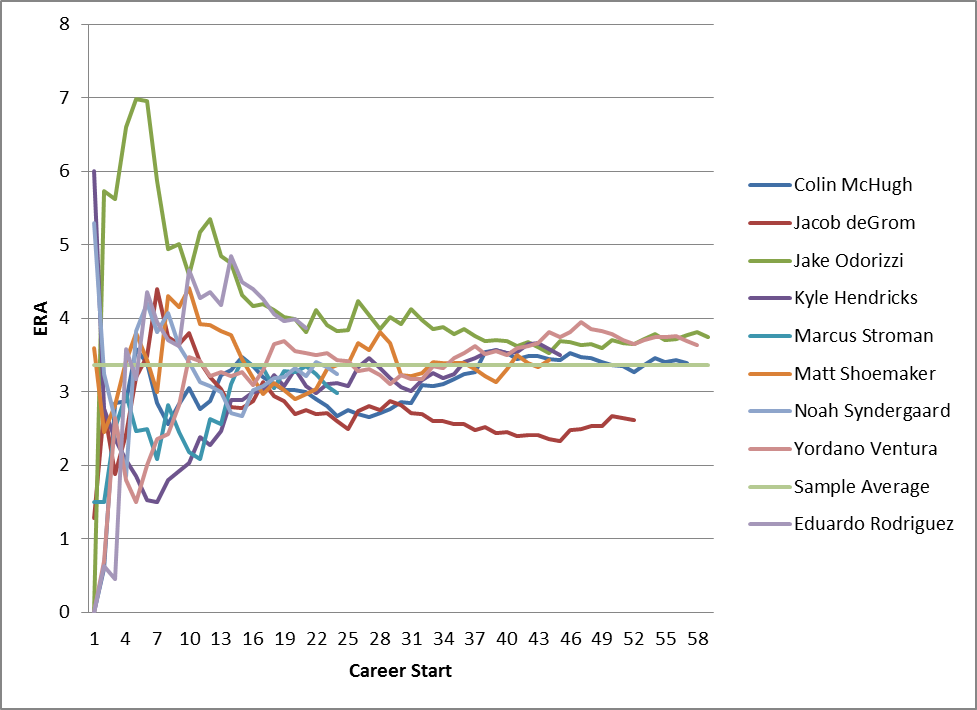

I must first admit that I was interested in this topic a few weeks back, when I noticed that Eduardo Rodriguez had his ERA back down under 4.00 with a string of 7 straight high quality starts. Eduardo started off hot (1 ER allowed in his first 20 innings), cooled off (his ERA was as high as 4.84 after a mid-August start against Miami), and then he adjusted and finished with a 3.85 ERA. It seemed to make perfect sense, but as I looked at more and more pitchers, my graph ultimately looked like this:

That’s not pretty. I took a look at 9 young pitchers who were rookies in either 2014 or 2015. I placed an emphasis on those that are fun to watch and/or fun in general. In the interest of pure statistical analysis, I likely should have looked at all pitchers who were rookies in 2014 and made at least 15 starts in each of the last two years. But that’s no fun. Baseball is fun and my blogging is, too. Sampling from my “fun” criteria and among pitchers who were rookies within the last two years and have made at least 20 starts yielded the following list: Colin McHugh, Jacob deGrom, Jake Odorizzi, Kyle Hendricks, Marcus Stroman, Matt Shoemaker, Noah Syndergaard, Yordano Ventura, and Eduardo Rodriguez.

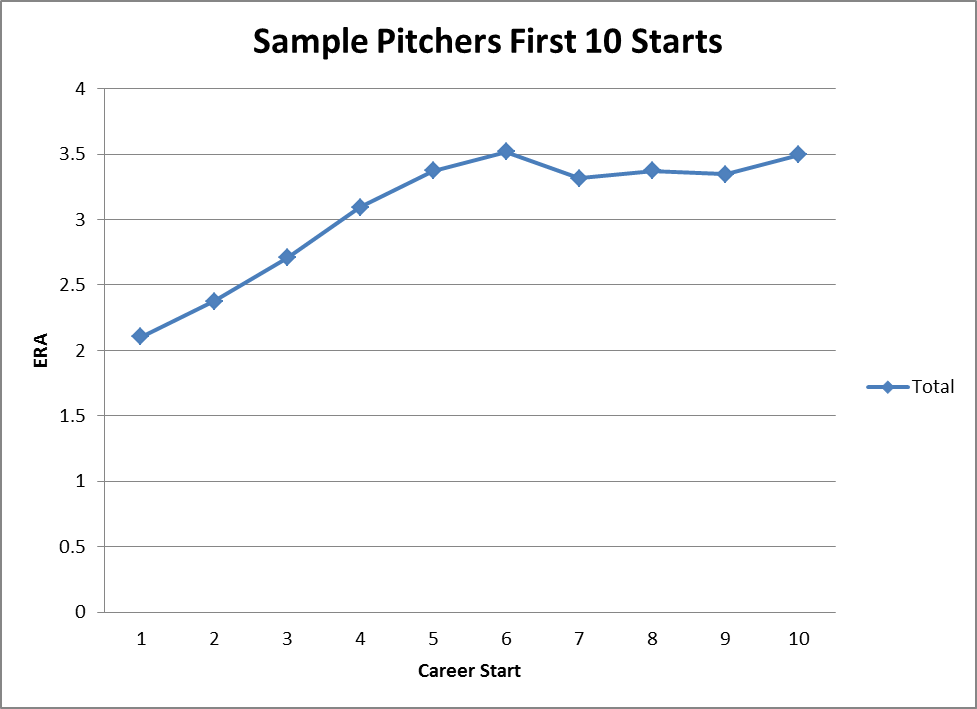

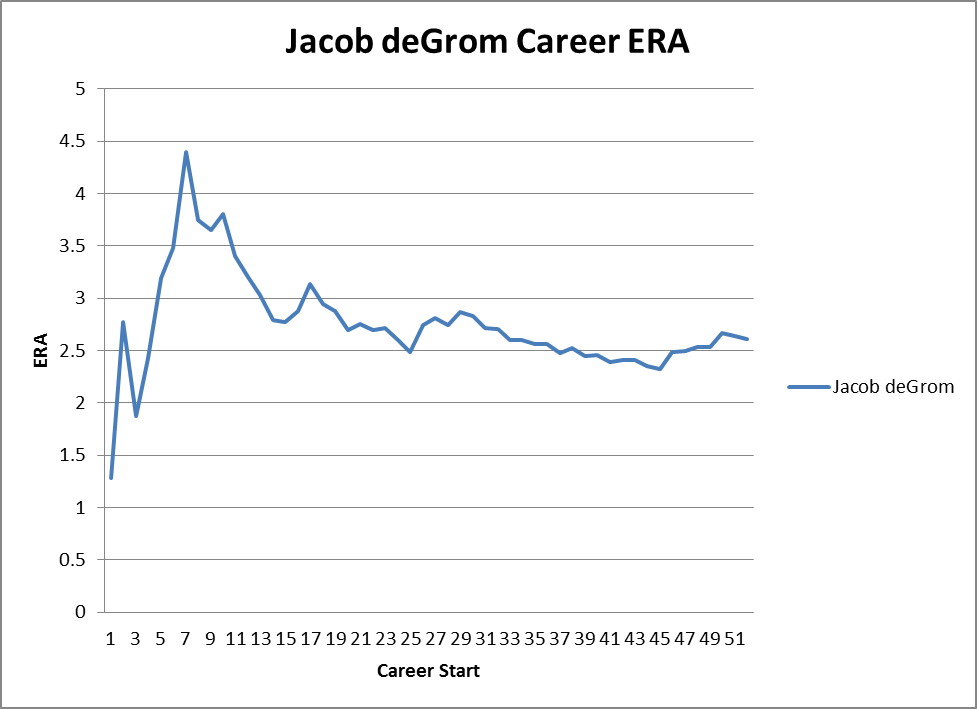

That mess up there does tell us something. First, Jacob deGrom is really good. That’s his little red line down there. Second, there’s a whole lot of noise in those first 10 starts. That is to be expected as basic statistics tells us about small sampling, but if you look at the group on the whole over those first ten starts, the trend appears to be there. You’ll notice that the ERA in those guys’ first starts is 2.10. It then rises to 3.51. The overall sample ERA was 3.36, so the trend down from that initial struggle seems to be real.

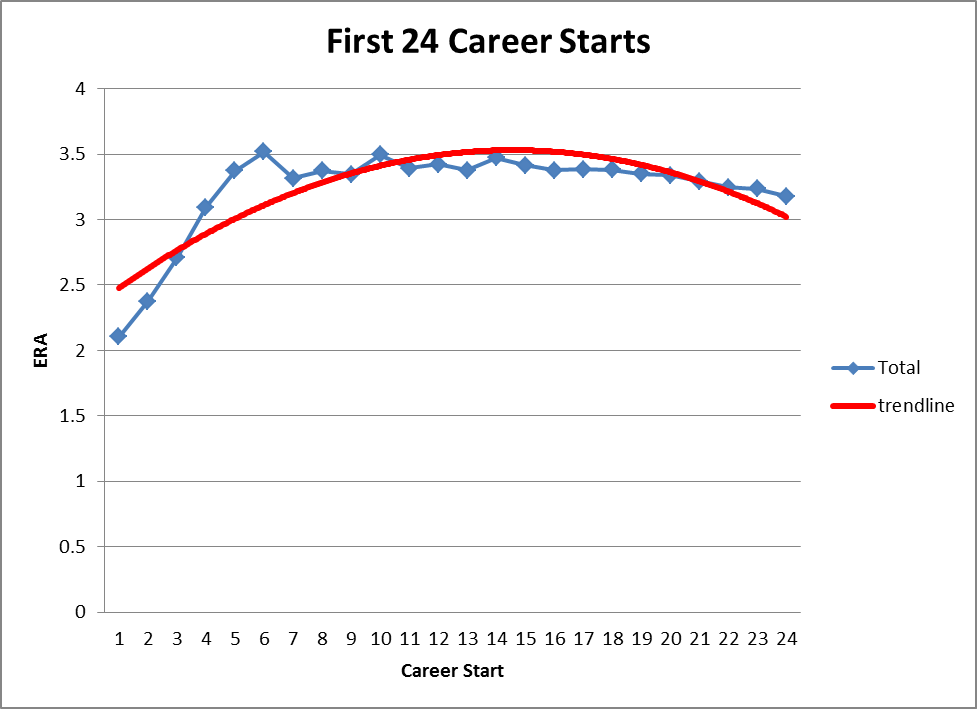

But even 10 starts is small beans in the world of the 162-game regular season. Each of my sampled pitchers has made at least 24 starts so, lets look at those 24 starts in aggregate.

Maybe that downward trend isn’t entirely fair over those last four starts. They include Marcus Stroman’s four starts at the end of this year, when he posted a 1.07 ERA to help push the Blue Jays into the postseason. Much has been made of the adjustments that Marcus Stroman has made this year in his return from an ACL injury. Stroman’s injury makes his case quite different from Colin McHugh’s, who saw his first 24 starts all take place within the 2014 season (I didn’t include his 2012/13 cameos).

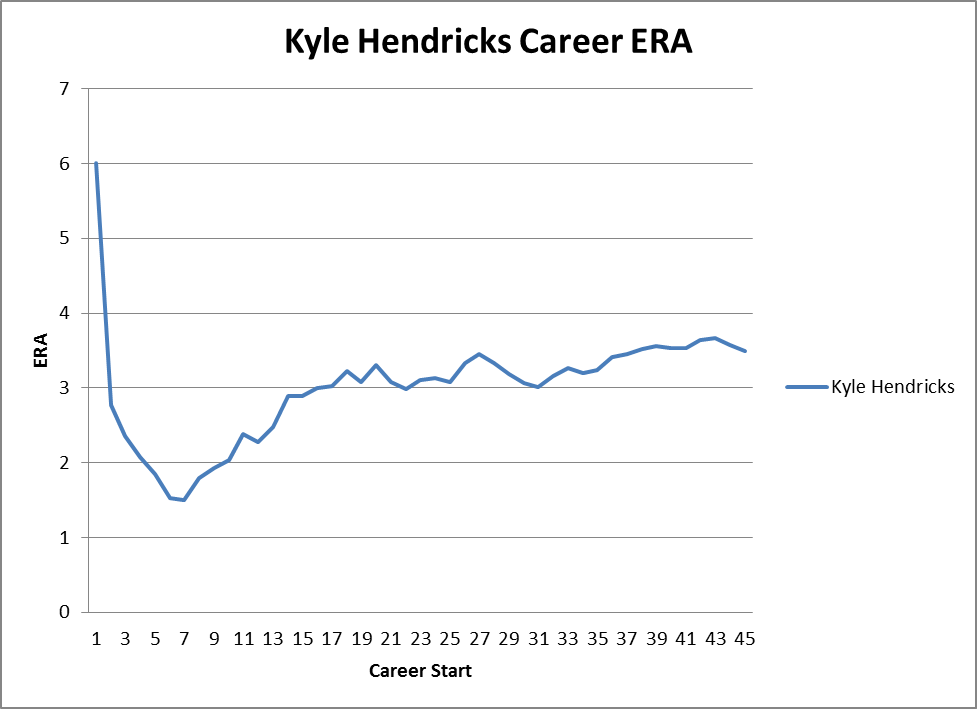

I’m not sure that much can be gleaned from my sample of pitchers other than to say that the trendline appears to back up the old baseball saying. Further, I want to withhold any bold stances that may be contradicted by a blogger with a larger sample size. But the graphs of two individuals cannot be refuted.

Notice that both had initial success. Hendricks’ success lasted his first 10 starts or so, while deGrom’s excellence lasted just 4. The struggles happen, but deGrom has been able to adjust and overcome that peak in ERA at the beginning of his career. Kyle Hendricks has yet to make that incline in ERA look like a peak, instead of a plateau. His plateau is still quite good (career 3.49 ERA), but if he is able to make an adjustment to the hitters’ adjustment, he will make that next leap. Jacob deGrom has gotten better by gaining an extra 1.5 mph on his fastball. That’s one way to adjust to hitters at the big league level. Kyle Hendricks simply needs to make his next adjustment if he wants to take another step toward the upper echelons of the pitching heirarchy.

-Sean Morash

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!