By Rob Goldman, AngelsWin.com Historical Writer –

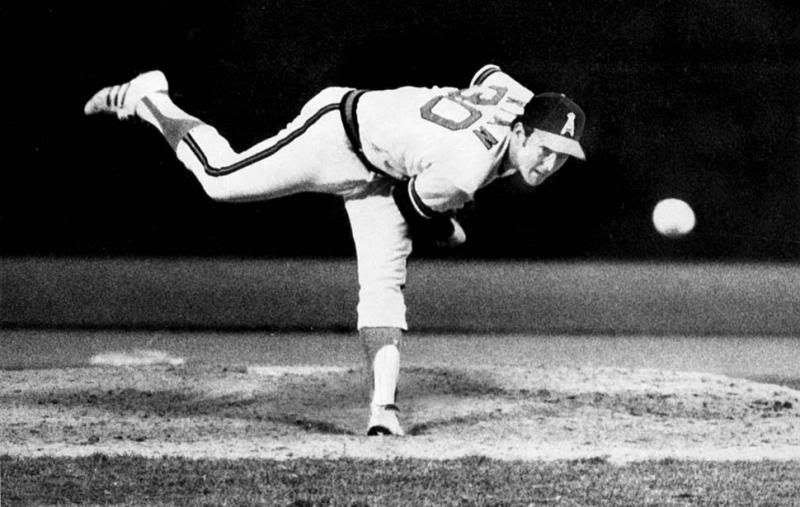

In 1974 the milestones for Ryan continued to pile up. On August 30, he became the first pitcher in modern baseball history to have three consecutive 300-strikeoutseasons. On September 7, he broke the record for which he is perhaps most famous.

Rockwell-American International provided parts for the NASA space program and the U.S. Army. George Lederer, the director of communications for the Angels, had an idea about using the company’s finely calibrated technology to measure the speed of Ryan’s pitches. Rockwell-American was willing, and using a device more accurate even than today’s hand-held radar gun, Ryan’s fastball was unofficially clocked at 100.9 miles per hour in a game against Detroit. After further refinements were made to the equipment, the Rockwell-American instrument was brought to the Big A to take an official reading.

In the ninth inning, on a 3-1 count against Lee “Bee Bee” Richard, Ryan’s fastball was measured at 100.8, easily surpassing Bob Feller’s 1948 mark of 98.0. Ever since, that pitch has been deemed by Guinness World Records as the fastest ever recorded.

But according to Angels catcher Tom Egan, it wasn’t the fastest pitch Ryan ever threw.

“If that particular pitch was 100.8, then I would have to say he probably threw a few on other days that reached 105,” he said. “I don’t know whether they were strikes or not, but he could get it up there.”

The Guinness pitch was belt high, says Egan, and balls Ryan threw from the belt up to the letters were always faster.

“I’ve thrown harder,” Ryan himself said after that game. “The big build-up before the game got to me. I was a little tense and couldn’t concentrate. I was worried I’d try to throw so hard, I’d blow the ballgame.”

After the pitch to Richard, Ryanitis picked up a notch. Opposing hitters already had enough on their mind facing Ryan, and now they had to contend with the fact that every time they went to bat against him, they

were facing the “Fastest Man Alive.”

Heading into the last home stand the Angels were dead last in the AL West, 25 games behind Oakland.

Ryan’s last scheduled start was on the September 28, against Minnesota. With 352 strikeouts he was fast approaching his own record of 383. Williams gave him the option of another start against Oakland later in the week, but Ryan indicated little enthusiasm for that.

On the morning of the game, he was scheduled to attend autograph signings in Huntington Beach and Newport before heading to LAX to pick up of his pal from Alvin, George Pugh. The plan was for Pugh to take in a couple games, then caravan back to Texas with Ryan and teammate Dave Chalk. Ruth and Reid had already left for Alvin.

Ryan was tired and not looking forward to pitching that night. He’d already won 20 games, and there wasn’t anything riding on the contest. But as he tossed in the bullpen before the game, he recalls, “I could feel the extra hop in my fastball. So I told Tom [Egan], ‘I think I’ll let it all hang out. What have I got to lose?’”

“When we started the game, I signaled down for a fastball that looked like it was going to be in the dirt, but when I went down to block it, it rose about two feet,” recollects Egan. “The umpire called it a strike and told me I’d better sit still or he wouldn’t be able to see the pitches. From then on I knew [Ryan] had a good day going.”

As the game progressed and the Twins remained hitless, there was probably more pressure on Egan than Ryan. Nolan had already been through this numerous times; but this was Egan’s first shot at a no-hitter, and he didn’t want to call a bad pitch or make an errant throw that would give another Minnesota batter a chance to wreck it.

George Pugh remembers that it was lonely that night in the Big A. “The Angels were [24] games out of first place and nobody was at the stadium,” he said. “I was sitting behind home plate, and there are so few people in the stands that Nolan later told me he could see me sitting there.”

Back in Alvin, Ruth—who’d missed her husband’s first two no-hitters—kept track of the game by repeatedly calling the stadium switchboard operator for updates.

“I would ask the operator the score and how Nolan was doing, and she would just say ‘He’s doing okay,’ because she was afraid she might jinx him. The third time I called, I said, ‘Lizzy, how many hits has he given

up?’ She said, ‘Uh…none.’

“Well, that’s when I was really aggravated I wasn’t there. I was excited but I also felt left out, because Nolan’s sister and all of his friends were there, and I was sitting at home in Texas.”

In the ninth, Pugh had a nerve-wracking moment.

“The Twins had some really good players, including Harmon Killebrew. Since it was the last weekend of the season, they were resting him, but now with two outs in the ninth they called on him to pinch-hit.

I’m on the edge of my seat thinking, Aw, god, Harmon Killebrew! Nolan only needs two outs. They could have gotten the other guy out easily and now they pinch-hit Harmon Killebrew! Jeez.”

But Killebrew walked, which brought Eric Soderholm to the plate. Ryan got two quick strikes past the big infielder. Once again, the pressure was on Egan,

“I called for a curveball,” Egan recalls, “and said to myself, ‘Tom, if you catch anything clean the rest of your career, you catch this one!’ Well, Soderholm swung and missed, and the rest was history.”

Soderholm’s whiff sealed Ryan’s third no-hitter. It was his 15th strikeout of the night, giving him 367 for the season. Just 16 more would break his own record, and again Dick Williams offered to let Nolan pitch the

final game of the season.

“I’ll settle for this,” Ryan said. “I’m worn out. It was a struggle. Anytime you are as wild as I was, it’s a struggle.”

At the post game birthday party at Ryan’s house, Pugh told him, “Man, was I nervous when Harmon Killebrew came up.”

“Why?” asked Ryan in genuine puzzlement.

“Nolan,” said Pugh, “it’s Harmon Killebrew!”

“He looked at me like I was crazy,” recalls Pugh, “and said, ‘So what?’ It turned out I had put more pressure on myself than Nolan did on himself.”

Overall, Ryan was 21–16 with a 2.89 ERA, had completed 26 games, and pitched a personal-high 332 innings. His 367 strikeouts were the most in either league, and his combined 750 Ks over the last two seasons was also a record.

But Ryan also became the first pitcher since Bob Feller to walk more than 200 batters. On April 5, against Chicago, he walked 10 batters but won 8–2.

Perhaps most striking was that he had won 22 games for a team that finished dead last and scored the fewest runs in the American League.

In a column titled “The Curse of Nolan Ryan: It’s Pitching for the Angels,” Jim Murray pointed out that Ryan was hardly alone when it came to pitching for underachieving clubs, citing Dizzy Dean, Grover Cleveland Alexander, and Walter Johnson as examples of other pitchers who’d been in the same boat.

“Nolan Ryan is in the great tradition when he pitched impeccable ballgames for highly peaceable ball clubs,” wrote Murray. “But before Nolan Ryan breaks up any furniture or jumps the club, he should know that Walter Johnson was involved in 64 one-run games. But shucks! He won 38 of them.”

According to Murray, Ryan just plain threw too many pitches. To become a complete pitcher, said the columnist, Ryan needed to narrow his strike zone.

“Of his 172 pitches in his record-breaking game against the Red Sox,” Murray wrote, “114 were strikes and 58 were balls—which is an inefficient use of a million-dollar instrument.”

In 1975, after three years of relatively good health, Ryan’s million dollar instrument would get the most severe test of his career. It would push his faith and fortitude to their limits.

© Nolan Ryan, The Making of a Pitcher, by Rob Goldman – 2014

Book Signing- Saturday, June 7th, B&N in Orange, 791 South Main St. – 1:00-4:00

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!