Every year at the end of the season I update Burning River Baseball’s top ten positional lists to reflect the most recent season’s statistics. While there isn’t a whole lot of movement year to year (given that there have been 116 seasons played before this one), the biggest jumper in 2016 may have been a controversial one as Cody Allen moved from #4 to #1 closer in Indians history. His first two games this season show why that move was completely justified.

While Allen has only been the Indians closer since 2014, he has already moved into 5th in Indians history in total saves with 94. Of course, this overvalued statistic is not how we should judge any pitcher, even one who’s specific role is completing saves. In fact, we shouldn’t take any simple counting stat too seriously without reference as they can be greatly effected by longevity more than anything else. Doug Jones was the Indians first real, long term closer and he accrued 129 saves for some pretty bad teams, but he also had more save opportunities than any other pitcher in Indians history. Bob Wickman holds the team record with 139 and had an excellent conversion rate, but wasn’t always dependable and had two absolutely terrible seasons surrounding his injury lost 2003 out of six total seasons.

For Allen, the most important counting stat is total strike outs. He ranks fourth in Indians history among relievers already with 398, despite coming in 14th in total relief innings. In his first two games this season, he struck out batters for all six of his outs and hasn’t walked a batter. In the 2016 postseason, he struck out 24 in 13.2 innings and his 25 total postseason strike outs now rank 8th in Indians history among all pitchers. For comparison, Bob Feller and Bob Lemon who pitched a combined 44 post season innings struck out a total of 24 batters. Back to the regular season, Allen is only a couple games away from passing Rafael Betancourt for third most K’s by an Indians reliever and he should easily move into first before he hits free agency after the 2018 season.

As I said, however, the total of counting stats doesn’t mean a whole lot. Why Allen’s strike outs are important is what happened during his save in game two against Texas. The fact is, every pitcher is going to give up hits. Mariano Rivera ended his career with 998 hits allowed and a WHIP of exactly 1.000 meaning he had one runner reach base for every inning he ever pitched. The problem isn’t allowing base runners, it’s what you do with them.

After giving up doubles to Nomar Mazara and Mike Napoli to start the 9th and bring the game to within one run, the strike outs were integral to finishing the game without extra innings. A contact pitcher like Jones or Wickman may have retired the next three batters, but still allowed the run to score. A fly out or ground ball to left would have easily allowed the pinch runner Delino Deshields to move to third where he could have scored on a sacrifice fly, ground out or wild pitch. With Jurickson Profar coming up after Rougned Odor struck out for the first out, the Rangers could even have tried a safety squeeze to push the tying run home. It is dramatically easier to keep a runner from scoring from second than from third and the only guaranteed way to keep that runner from moving is by striking every one out.

While no pitcher can strike every batter out (even though Allen has done so to this point in 2017), Allen is the greatest pitcher in Indians history at trying. As you’d expect given his K total and relatively low innings total, Allen has the best K/9 in Indians history among all pitchers with at least 40 IP and he has over 300 innings under his belt. Impressively, three of the top 4 qualified K/9 pitchers in Indians history are on the active roster with Corey Kluber and Danny Salazar joining Allen.

While the overall effect could be due to an increase in strike outs throughout the league (ever since MLB pitchers broke the K/9 record in 2008, they have broken it again every single season since and are currently outpacing 2016 although it is extremely early), Allen has been particularly adept, coming in 19th in MLB history in K/9, 15th since he made his debut in 2012. Among all relievers since 2012, only Dellin Betances, Craig Kimbrel, Andrew Miller, Kenley Jansen and Ken Giles have a better K/9, BB/9 and HR/9 than Allen. While this may make Allen the second best reliever on his own team, it also places him in the top six relievers in all of baseball in the most important aspects of the relief game.

How does he do it? While it hasn’t been very effective so far in 2017, in his career, Allen has never allowed an average for a full season above .160 against his knuckle-curve. Like Miller’s slider, it is this pitch that differentiate’s Allen from other single pitch relievers. Essentially, Allen has always been a two pitch pitcher, throwing his curve between 25 and 40% of the time, but when he does throw it, he averages a swing and miss rate of higher than 20%. When players do put his curve in play, the results are overwhelmingly ground balls and he has one of the best infield defenses in baseball behind him.

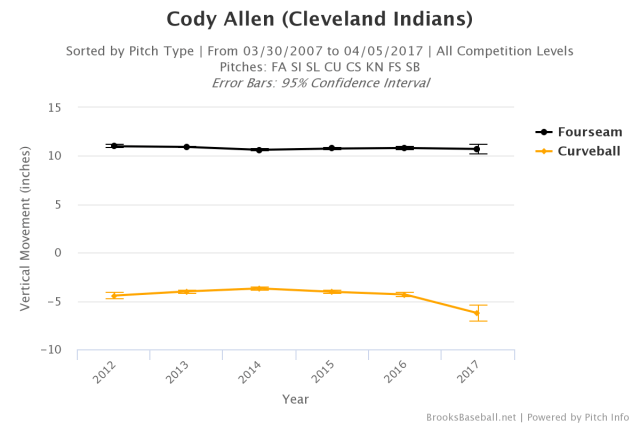

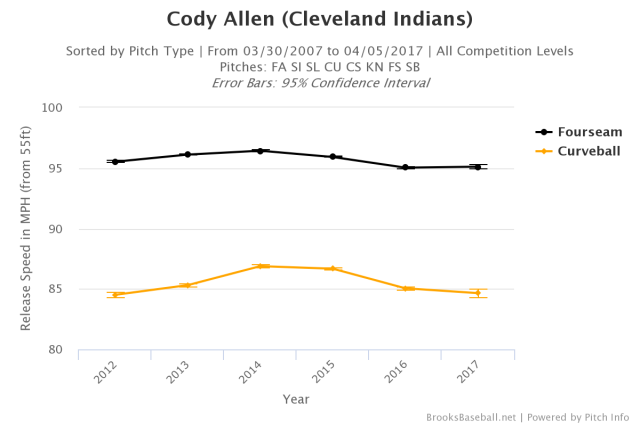

The movement alone on his curve is enough to make hitter miss, but it’s the fact that he uses it as a change-up that makes it so devastating. For a batter to be looking fastball (and with his regularly above 95 MPH, the batter has to look fastball), then see not only a change in speed, but in direction, it is almost impossible to square up the ball. The two charts below show the difference in the two pitches in velocity and movement.

Hitters not only have a drop in speed to adjust to of about 10 MPH, but a physical drop in the strike zone by more than 15 inches. From time to time, fooling hitter as badly as he does has hurt him. If contact is made, often times the hitter will hit it weakly where the defense isn’t, leading to hits that may have not happened if he just threw it down the middle without movement like Zach McAllister. While simply putting the ball over the plate can be successful in the short term, Allen’s multiple pitch options have allowed him to retain success over the long term and should keep him there for good.

Now going into his fourth season as the closer, Allen has proven that it isn’t a gimmick that can be easily researched and overcome by opposing hitters. By striking out batters at a rate never before seen in Indians history, Allen has quickly become the Indians greatest closer and there is little reason to think he won’t continue this level of play through his final year under team control in Cleveland (2018). Whether the Indians are able to extend him prior to free agency or not (he will command an elite relievers salary and Jansen just signed for five years, $80M), Allen will hold a special place in Cleveland baseball history for a long time.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!