If you have regularly listened to Chip Caray over the last couple of seasons, you’ve heard something like this:

“Freddie Freeman beats the shift again!”

Or, to be more blunt…

“Shift this!”

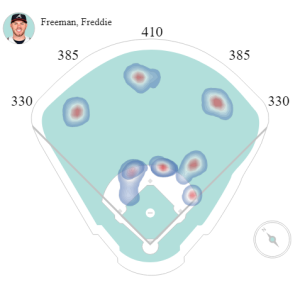

This happens because few players are shifted on more frequently than Freddie Freeman. Only 23 players were shifted on last year as a higher percentage of their their plate appearances than Freeman. That’s out of 696 players. 66.9% of the time, Freeman was shifted on. There are some who call that nice. In fact, Statcast has a nice little graph that shows defensive position as teams game-plan to face Freeman. This graph is from 2018.

Notice that the second baseman is often in short right field, the shortstop moves over to the second base side, and the third baseman plays close to second base on the shortstop side. We’ve even seen some managers like Joe Maddon put all four infielders on the right side of the infield. This is despite what we hear about Freeman beating the shift. At least, that’s the narrative that we hear with many members of the Braves media questioning why teams even bother shifting against Freeman. Would you believe it’s because it works? I mean, you should. Teams aren’t that dumb. They don’t shift because it’s a fad or all the cool kids are doing it. They do it because it works.

I want you to look at that image from Statcast again. What stands out the most to me is not that the second baseman is playing in short right field but how the outfield plays Freeman. They don’t shift like the infield does. In fact, if anything, they shade him slightly to go the other way. And this is where the whole “Shift This!” narrative fails to take into consideration the context of shifting.

Teams are not playing the player, they are playing the tendencies of the player. And those tendencies are easy to see, graph, and prepare for. To be clear, Freeman’s going to do Freddie Freeman things because he’s an elite hitter. But last year, teams limited Freeman to a .365 wOBA when they shifted on him. It’s comical to say “limited” when the wOBA is still so high, but when they didn’t shift on him at all, the wOBA was .404. So, that’s not nothing.

But many people get lost in the wrong numbers. Overall, Freeman shows a slight pull tendency. He pulls the ball about 40% of the time, goes the other way roughly 26% of the time, and goes up the middle the remaining 33% of the time. That’s what he’s done over his career. So, if you only look at that, you’re going to think that extreme shifts on Freeman are dumb. In fact, as 680 The Fan’s Kevin McAlpin pointed out yesterday, “135 of Freeman’s 191 hits were either up the middle or the opposite way to left.”

But again, remember, they are shifting him to pull on the infield. And that’s where this narrative seems to get destroyed of Freeman beating the shift. If you play him to pull on the ground and he consistently beats the shift, then we should see in the numbers that he goes the other way frequently on the ground. After all, that’s where practically nobody is playing. I bet you know that’s not what we see, right? Here are some career stats on grounders.

Opposite: 10.4%

Central: 32.0%

Pull: 57.7%

Also, these numbers have only trended more-and-more toward an extreme pull profile on the ground. The last two years, nearly 64% of all grounders were pulled and only about 9% went the other way. Compare this with flyballs. During his career, he has a pull-rate on just 19% of flyballs. He does show more pull tendencies on liners (42.5%), but also goes the other way with more frequency (23.8%). Of course, on liners, the success rate is so high that it really doesn’t matter how the defense plays him. What do I mean? Well, he has a .686 wOBA on liners. You can put the entire Phillies’ roster out there and Freeman’s still going to get hits when he hits liners.

Since liners are nearly indefensible unless hit right at a player, you prepare for what you can defend. Flyballs also carry a high wOBA because that’s where most of your home runs will come from. Can’t defend a homer, but you can try to defend the non-homers.

All of this should make sense, right? Again, look at the picture I shared from Statcast. Freeman goes the other way about 10% of the time on grounders. As a result, defenses play him where he’s going 90% of the time. On the other batted balls, especially flyballs, Freeman is more likely to go the other way – though not to such extremes as he pulls the ball on the ground. Defenses shade him slightly to go the other way in the outfield.

Just to clarify, none of this is to say that Freeman needs to change how he hits or anything. The man has a career .375 wOBA – a mark he has eclipsed each of the last two seasons. Some might suggest that going the other way might make him even better and I’m game if Freeman wants to give that a try. On the other hand, it might lead to other issues for him to focus on just serving the ball the other way on the ground because it’s an “easy single.” I’m cool with the big man continuing to do things that come more natural to him.

Freddie Freeman will still beat the shift from time-to-time. Again, he’s one of the best hitters in baseball. But he’ll lose a number of hits because of the shift as well. And because that number will always be higher than the number of times Freeman goes the other way on the infield, teams will continue to do it. Further, most of the times that Freeman does “beat the shift,” he’s actually hitting it the other way to the outfield. Where the outfield is playing him to hit it. He’s still going to get his hits. But let’s not ignore that shifting against Freeman is the right play for every team in baseball.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!