I have decided to reboot the “History Lesson” series that begain in October of last year with this post, not because I want to bore you all to death, but because the off season is the perfect time to get reflective and slightly off topic.

I have decided to reboot the “History Lesson” series that begain in October of last year with this post, not because I want to bore you all to death, but because the off season is the perfect time to get reflective and slightly off topic.

Two seconds… the backwards pass… Fright Night, the Marinovich drive, all painful moments that are seared into our collective memory as Cougs. But did they really unfold as we remember they did? This past weekend we recognized Memorial Day and all of this remembering had me thinking a lot about, well… memory, a subject far more complex and interesting than we often acknowledge.

My own exploration of how and what we remember begins and ends with the writings of one particular old soldier who happened to have passed away just days before Memorial Day. The lessons he taught me about memory are clearly demonstrated in my own recollections and those of my friends in over three decades of following our Cougs. In those lessons lie the roots of all the legend, myth and lore that surround the game and the team we love.

Still with me? If so, there’s more after the jump…

Paul Fussell, 1924 – 2012

Paul Fussell, 1924 – 2012

Thankfully, Second Lt. Paul Fussell didn’t die in combat, despite being on the receiving end of a German artillery shell in France. (Watch this short segement of a Tom Brokaw interview with Paul Fussell) He survived his wounds and lived to a ripe old age, long enough to write some of the best books I have ever read about society, culture, the English language and, yes, war. To this day The Great War and Modern Memory is the best book I have ever read. But our subject today is not war, it is memory, and in his books Fussel explores in great detail the narrative devices that shape what we remember, and how.

Case in point; Fussell demonstrates how irony became a dominant narrative device in memoirs of the Great War (and all wars, really). As anyone with even a passing interest in history knows, all wars were going to be “over by Christmas”, all attacks were going to be “walk-overs” and so on. Irony, or perceived irony, makes a memory stand out, and often when there is no irony present, our minds will invent it as a means of retaining that memory. Hence, the same ironic narrative shows up over and over in reminiscences about war, like the infamous condolence telegram arriving just as someone was writing an overdue letter to the deceased, or the last minute change of plans that proved fateful (“Hey Mac, wanna trade foxholes?”). Whether these stories are literal truth, or not, what they tell us is that in a world where everyone was getting “the telegram” or having buddies vaporized in their fox holes, irony provided a way to preserve the cataclysmic power of that moment in a world where “cataclysm” was the new normal and such events were no longer particularly eventful (i.e., memorable) on their own. This is one way to explain why such a large percentage of rememberances of war are full of irony. That, or every war is one long and bloody Monty Python sketch. (Joseph Heller and Robert Graves would argue the latter)

Of course the Cougs don’t fight wars, they play sports. So how does this relate to our experience as fans? The discussion of the pervasive irony in memories of war highlights a crucial characteristic of all memories… that is unless you are Rain Man, all memories are selective. We can’t possibly recount every detail of every play of every game, so our memories of our Cougs consist entirely of what we choose to remember. Further, those memories themselves are then wrapped in whatever narrative device needed to ensure they are the ones that persevere through time, be it irony, betrayal, tragedy, etc. Selective memory is why there are few things as unreliable as an eye witness. One of those few things, is a sports fan. I’ve come to realize over the years that my Cougar memories are often wrong, or at least heavily fictionalized. Here is an example:

A few years ago I was roommates with a buddy I had grown up with in Pullman. We were lifers, Cougs since we could crawl and we had tons of shared memories of all the legend and lore of the 80’s and 90’s Coug teams. We both would have accepted that our childhood memories of RPM and the Aloha Bowl and Palouse Possee were probably shrouded in a bit of the fog of imagination, but one lazy afternoon we discovered, to our astonishment, that even the most recent memories contained more than just a figment of our imgination. It was Apple Cup week, and FSN was replaying all the old classic games. The Snow Bowl was in heavy rotation, of course, but there were some classic Husky triumphs as well and for the most part we skipped those. But something made us sit down and watch the 2002 Apple Cup. I know, right? What Coug fan could possibly bear to do that? Basically we both looked at each other and admitted, that despite being in the stands that day and despite it being one of the most profound heartbreaks of our lives, all we could remember was a single play… the infamous “backwards pass” call against Matt Kegel in overtime that sealed the Dawgs victory. If there was one thing we were sure of in life, as sure as the sun would rise in the east the next morning, it was that the Huskies had stolen one from us in that Apple Cup.

Coug fans, you may want to sit down for this… we were wrong. Dead wrong. In fact, it was our Cougs that had come OH SO CLOSE to stealing a game the Huskies should have won. And I’m not even going to contest that the pass should have been ruled incomplete. It appears to travel at least a yard and a half downfield to my eyes. But that isn’t the point. Not only were there literally dozens of other plays in that game that had as much to do with the outcome as that backwards pass (remember Reggie Williams playing DB against Mike Bush on a goal line stand?), but one particular play was an egregiously bad call against the Huskies that ensured the overtime where the Cougs had a chance to win. Late in the game Cody Pickett fired a TD pass to the back of the end zone where his receiver made the catch with his foot probably a half yard or more in bounds. This play was ruled incomplete, and it was a terrible call. In fact, it was much worse than the call in overtime that ended the game. The Dawgs settled for a field goal and the resulting 4 point swing ensured that the game would go to overtime instead of ending in regulation with a Husky victory. Look Coug fans, I know this hurts, but we’re not alone. The world of sports is full of moments that are generally not remembered correctly. Take these for instance:

- Buckner’s error was not in the deciding game of the 1986 World Series.

- The 1980 US Olympic Hockey team did not win the gold against the Soviets.

- The infamous Bartman interference would have only been the 2nd out of the 8th inning.

- In the 1970 NBA finals Willis Reed scored the first two baskets for the Knicks, then didn’t score again for the rest of the game.

To some of you, none of those facts will come as a surprise, but I bet a couple of them sent more than a few of you scrambling over to Wikipedia saying “WTF, really?” When it comes to sports, exageration, ommission, false assumptions and outright fabrication are more the rule, than the exception. Even in an age where almost everything is televised and available for quick reference on Youtube, we still live immersed in a world of lore and myth. How is that possible? One reason is that to sports fans, impirical truth is not important. The myth and legend of the games we love are what make them appealing to us. Sports is entertainment and it is much more entertaining to remember things how we want to remember them, than how they really happened. This, combined with the fallable nature of our memory as it is, means that despite an age of readily availble facts (with video evidence!), our myths and legends perservere. It’s enough to make me wonder if we really do want a playoff system, or do we actually relish the controversy that comes with the BCS and the bowls? Don’t you think Tulane is perfectly happy having a claim to the 1998 national championship?

I know there is a tendency to recoil at any suggestion that a long held belief is nothing more than a construct of your imagination, and part of that is the perceived accusation of lying. That is not what I am talking about here. I used to argue with Husky fans ‘til I was out of breath that they got a gift from the refs in overtime of the 2002 Apple Cup and it was the only reason for their upset that day. I was wrong, of course, but I wasn’t lying. I believed every word I was saying. I didn’t make a concious decision to ommit the Cody Pickett touchdown pass from my memory. Hell, I didn’t even know I had done that. But I did.

Just recently I was watching the terrific documentary Harvard Beats Yale 29-29, and it includes commentary from players in the legendary game interspersed with real footage from the actual game broadcast. In the film, one of the Yale players falls victim to the tricks of his own memory and describes a play where a key Harvard player was injured and how he had deliberately dealt the hit that did it. As he describes this incident the play is shown and, of course, the Yale player is actually quite a few yards away from the Harvard player when the injury occurs. His version of the play is completely made up, but he is not lying; not on purpose, anyway. He clearly believes he dealt the hit that injured the Harvard player. I am not the psychologist in the family, that’s Amieable. But I suspect she may agree that whats really happening there is the mind is just doing its job, arranging details of an event in a way that best supports the emotional health and happiness of the individual who is dealing with a painful memory. As an organ, the brain would rather be happy, than right.

http://youtube.com/watch?v=iaYshRf5-tU

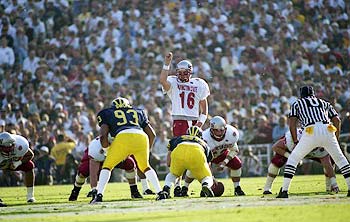

If you are as interested in this as I am, I suggest you go back and watch some of the old games that you think you remember so well. One thing that I have noticed is that a lot of the triumphant moments live in my memory as near perfect replays of what really happened… for example “the catch and the block” against USC in 1997. But a lot of the more painful moments have become muddied and obscured, perhaps as my mind tries to frame them in a narrative I can live with. Hence, we were cheated in 2002, instead of, the Huskies came into our house and beat us, just like the Boston fans focus on Buckner’s fluke error, rather crediting the Mets for beating them in game 7. If you’re not sure where to begin, why not with one of the greatest moments in all of Cougar lore and legend… the 2 seconds at the end of the 1998 Rose Bowl. Ask yourself this; Did Nian Taylor commit an egregious offensive pass interference on the catch that got us within strking range of the end zone just before Leaf spiked the ball?

So I ask, how many of you remember that?

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!