In the first inning last season, Julio Teheran surrendered only a .220 batting average. That was part of an overall theme of not getting dinked and dunked against, leading to one of the lowest opponent’s batting averages in baseball. But that didn’t mean the first inning was a success for Teheran. He gave up eight homers and 25 walks over 31 innings. So, while hitters only hit .220 against him, they made those hits count. More to the point, half of the 26 hits he allowed in the first frame went for extra bases. And when hitters didn’t pepper the alleys and make souvenirs, they were getting on base as a .361 clip. It was the only inning in the first six frames that hitters posted an OPS above .735 against Teheran.

This hinted at a bit of a new development for Teheran. Whether by intention, mechanics, sheer bad luck, or a combination of the above, Teheran went from a strike-thrower to a guy who nibbled around the zone. That put him in a lot of unenviable counts, especially early as he tried to feel out what pitches were working or not and how the umpire was calling the game. To be fair, if it was by intention, the Braves have changed pitching coaches and that might not be as much of an issue.

As Teheran settled in, as did the results. While he still walked a few too many hitters and gave up his fair share of homers, he was competitive in a way he simply lacked during the first inning.

During his first two outings this spring, the trend remained for Teheran. And while Teheran has always struggled a bit more in the first inning over his career, his atrocious results in the opening frame last year could give the Braves reason to try one of baseball’s newer experiments – the opener.

Made somewhat famous by the Rays, and especially Sergio Romo, last year, the opener has its supporters. It also has its detractors like Madison Bumgarner, who said, “If you’re using an opener in my game, I’m walking right out of the ballpark.” Other starters have spoken distastefully of the idea, but many of those starters are not the type of pitcher a team would use an opener in front of anyway. An opener is meant for guys toward the end of your rotation, not the ones you expect to anchor it.

How does it work? It takes several principles we already know. Starters are pitching less than ever before, hitters are more successful the more times they face a pitcher in a game, and the best hitters are clumped together at the top of the lineup. It takes those principles and utilizes a higher leverage arm capable of matching up better with the top of the order for the first inning. Ideally, the pitcher succeeds. Next, the team goes to the “starter,” whose outing begins against the middle-and-bottom of the order where less talented hitters typically are. He’ll still have to face the best the lineup has to offer, but he’ll face them less than he would have if he started. And let’s remember – the only time we know for sure before a game starts that the first three hitters will hit in the same inning is in the first inning.

So, by getting through the first with a high-leverage arm, you hopefully shield a starter who isn’t exactly one of your top options from having to face Bryce Harper or Anthony Rendon three times in the same game. Seems simple enough?

Our own Michael Francis considered this subject last summer, noticing that, as you might expect, Teheran was very vulnerable to the #1, #3, and #4 hitters in the order. And opener could limit how many times those guys destroy his hopes and dreams. Also, like I mentioned, by staggering the lineup, it’ll be easier to navigate through the top of the order because you might be facing the lead off hitter – who on-based .359 against Teheran last year – with two outs rather than seeing him lead off an inning (especially the first).

Of course, there is a problem here and it’s one that I heard from a few followers after throwing around this idea yesterday on Twitter. Would Brian Snitker entertain the idea? I think that depends on what the front office is pushing. While Snitker balked soon after experimenting with Ender Inciarte in the #9 spot in the lineup – a move I particularly like – he also was open to extreme shifting and other info being passed down by the analytically-inclined front office.

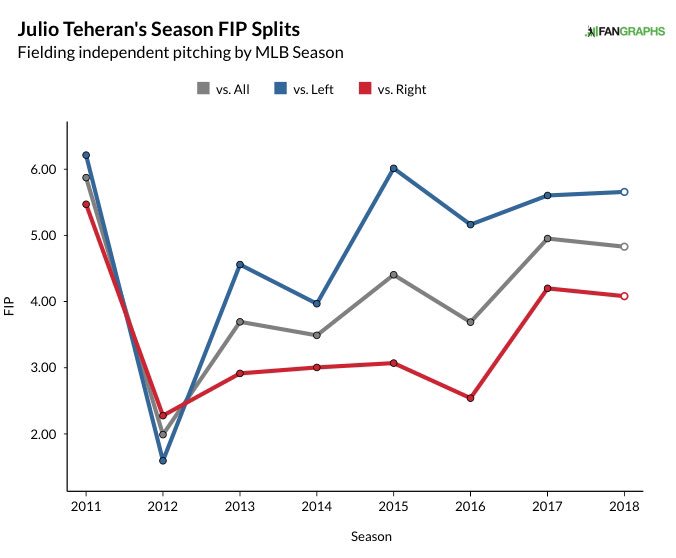

Just to be clear, there are other problems that using an opener wouldn’t solve. The biggest? That Teheran struggles tremendously against lefties. As our buddy Stephen Tolbert pointed out, Teheran does extremely well against right-handed hitters but has been a lost cause versus lefties since 2015. I’m stealing the image he stole from Fangraphs like a friend does.

So, no, just using an opener doesn’t fix the underlying issues with Teheran. His limitations remain. Quite frankly, his splits only reinforce a thought I’ve had for a few years about how Teheran badly needs to refocus on his changeup. But that doesn’t appear likely. But what an opener could do is limit what Teheran’s weaknesses do to the team and help his results. Yes, we can talk all day about how Teheran isn’t the pitcher he was expected to be, but the more important subject here is how best to utilize Teheran to help the Braves repeat as NL East Champs in 2019.

One of the basic principles of being a good manager is to put your players in position to best succeed. Does that make Brian Snitker a bad manager if he doesn’t entertain an opener for Teheran? No. I can’t say whether or not this experiment would yield better results. I can only look at the data and say it’s a possibility. And considering the first inning troubles Teheran had last year, it’s worth a try.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!