-Contributor: Connor Dillon

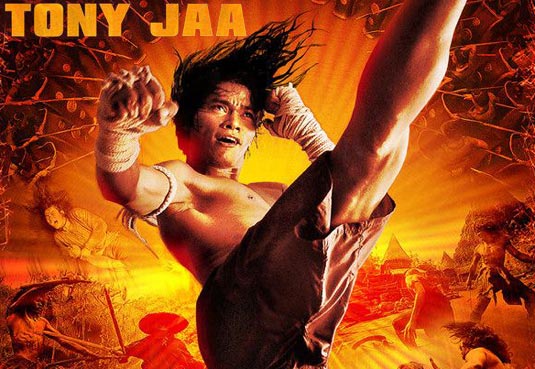

One of the main goals of martial arts films is to show the audience things we’ve never seen before, or think is possible. Because the focus of most martial arts films are a spectacle of physical actions, it allows the genre to go far. Ong-Bak is seemingly designed to do that, and at it’s release in 2003, Ong-Bak was the second biggest film in Thai cinemas. It was promoted as ‘No Stuntmen. No Wire Action. No Computer Graphics’. However, the interesting thing about Ong-Bak is that it comes from a country not known internationally for martial arts films, and as mentioned earlier Ong-Bak was second behind The Matrix Reloaded (then to My Girl), which has a vastly different approach to its fight sequences, and is an epitome of Hollywood’s commandeering of Asian martial arts choreography. This cannot be understated, as prior to recent times, the Thai cinema was not only dominated by Hollywood, but also by the cinema of Hong Kong, which had travelled down a path that involved a growing use of wire and digital work. What Ong-Bak is, is what Hong Kong films use to be. Its few special effects are allocated to a

Despite the lack of wire work in Ong-Bak, it is the potent tangibility that makes up Ong-Bak’s action scenes that elicits memories of a classic, lost Hong Kong cinema. Furthering it’s global reach are short messages to famous film makers from across the world like Steven Spielberg and Luc Besson, the latter of which eventually bought multi-territorial rights to Ong-Bak. After a screening in Toronto, Magnolia Pictures bought Ong-Bak to bring it to the audience in the United States, ignoring the commonly used approach of releasing an international film via DVD in favor of going to a theatrical release. It became so successful overseas that the second film starring Tony Jaa, the lead actor of Ong-Bak, has already been sold to distributors in Japan and the United Kingdoms.

New Thai Cinema

Compared to other established countries like Japan, Korea, and Hong Kong, Thailand is relatively new to international success in cinemas. This can be traced to a critical lack of 35mm during and after World War II, which was only eased during the 1970s. Prior to that, 16mm was the film of choice, which could not have a be synchronized to an audio track, forcing it to be dubbed live during projections. Also, up until roughly 1999, films were distributed nationally, but exhibition occurred internationally via Hong Kong and Australian companies, as well as the United Artists. What really helped the genre of New Thai Cinema kick off, was a growing feeling of nationalism in Thailand. Films like Suriyothai and Bangrajan set up Burma as an ancient enemy, allowing nationalism to grow under the umbrella of anti-colonialism.

In Ong-Bak there are references that follow this nationalistic trend of using Burma as an enemy, and in fact the martial art that takes center stage in Ong-Bak, Muay Thai, has several documents related to Thais using Muay Thai successfully against Burmese soldiers. In 1774, while the 13 Colonies were discussing taxes and petty things like freedom, Thailand had been invaded and several prisoners of war were taken. One, Nai Khanohm Tom, defeated twelve Burmese boxers in fights to the death, gaining his freedom and wives from the Burmese King. In Ong-Bak, there is an underground fight club that Ting (Tony Jaa) goes into to get money back from Hum Lae, a Nong Pradu villager (the same village Ting is from) who relocated to Bangkok. The second time Ting visits there, Hum Lae attempts to use nationalist rhetoric to convince him to fight and defend a Thai male from getting killed against a foreign fighter after a barrage of insults against Thailand. Ting does not get involved until after a Thai female is slapped. Regardless of not being convinced by typical nationalist rhetoric, all the opponents Ting faces are foreigners. If a characteristic of New Thai Cinema is a particular sense of nationalism, there are qualities about it absorbed from transnational sources. This new genre caught the attention of transnational media like Asian Cult Cinema, and its more brutal films slapped with a label called ‘Asian Extreme’.

Duel of fists: The Thailand-Hong Kong connection

As Thai cinema has often been called the lost Hong Kong, so did Hong Kong be described as such as the lost Hollywood. However, such a comparison is a double edged blade, because it is somewhat insulting to be compared to the primitive silent-films era of Hollywood. Hong Kong cinema began to fall down from two distinct factors: the economic crisis felt across Asia, and the U.K. transferring Hong Kong from a Crown colony to a ‘special administrative region’. These allowed Thai cinema to rise, as they finally found the keys to be successful at the box office. Previously, Thailand was part of Hong Kong’s cinema empire, an effect of the marginal imperialism that Hong Kong began. In 1978, Hong Kong controlled 40.1% of Thai cinema, 52% in 1988, and rising to 52.4% in 1989. However, the interesting thing about marginal imperialism is that it goes through regions and blends with them in a takeover, which ends with a synthesis outcome of the various Asian cultures uniting. The obvious examples of blended culture are wuxia films, as well as the regional take on classic Hong Kong kung fu films like Ong-Bak.

Muay Thai, the combat sport that is the basis for modern kickboxing and featured in Ong-Bak, is theorized to have come from certain Chinese martial arts. It’s kicks are unique from other martial arts, as it relies on straight legs rotated from the hip rather than at the knee. Further connection to Chinese culture is found in the opera from northern China. Muay Thai incorporates

‘No stuntmen, no wire action, no computer graphics’: The Return of the Real

As noted by many viewers, Ong-Bak focuses on three things in its stunt work: truthfulness to Muay Thai (archival), lack of special effects (cinematic), and physicality (corporeal). Ong-Bak prefers to show the sequence of actions rather than a long take, revealing the movements or fighting to be as real as possible. For example, one of the more famous stunt sequences was Tony Jaa running on the shoulders of gangsters, a shot sequence that lasted 8 seconds total, and two of the three shots (7 seconds total) were of the action sequence in slow motion. The realness is also found in the fight sequences, which looked to be thrown with full force. Unfortunately, several viewers believed these physical scenes (running over shoulders, fight scenes) were staged and had wires. The proof exists in an extra on the DVD of Ong-Bak, as Tony Jaa arrives at press conferences and performs many of the same stunts without any wires at all.

This is in direct contrast to films like The Matrix Reloaded, which shot a similar scene with the protagonist Neo running across the shoulders and faces of his arch-nemesis, Mr. Smith. The biggest difference is the clear special effects that were used. All the Smiths were from John Gaeta’s stuntmen with Hugo Weaving’s expression digitally added in post-production, while Neo was

Since Bruce Lee’s time, many martial arts films have strived to be recognized as ‘real’, through uses of the long take, hazardous stunts, wire work, and CGI. WhileOng-Bak is using a different definition of ‘real’ compared to The Matrix Reloaded, its relationship to old school Hong Kong films makes it a clear rehashing of stunts to make them even more real. As such, Ong-Bak is a favorite among ‘old school’ fanboys and new fans alike, revealing a possible failing of the First Cinema’s technological supremacy.

-Connor can be reached @connorhavok.

(Source(s): Hunt, Leon. “Ong-Bak: New Thai Cinema, Hong Kong and the cult of the ‘real’.” New Cinemas: Journal of Contemporary Film. 3.2 (2005): 69-82. Print.)

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!