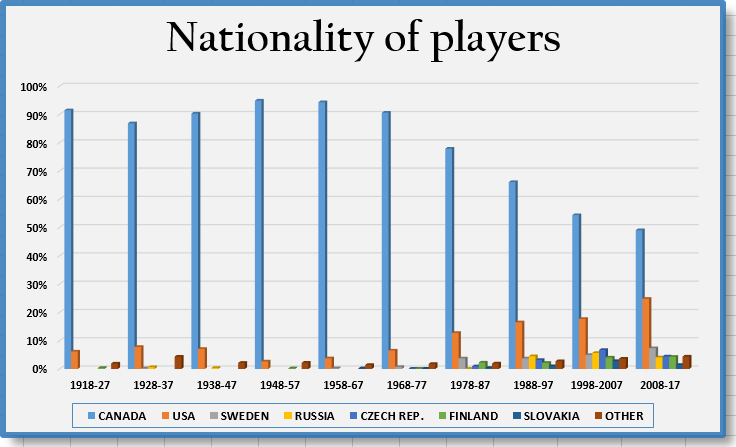

The 2017-18 Penguins opening night roster featured players from six different countries, as diverse as any of the NHL’s 31 clubs, a big step up from the first 60 years of NHL history when 95-98% of the league’s players were North American. That began to change in the late 1970s and into the 1980s when players from Scandinavia migrated west.

By the early 1990s, with the long-awaited fall of European communism, players from the former Soviet Union and its ideological satellite nations, started coming to the NHL in droves.

Indeed the Czech Republic more than doubled its representation in the NHL from 3.2% of all players during the NHL’s eighth decade (1988-97) to 6.7% in its ninth decade (1998-2007), the biggest jump of any nation in that time period. The Penguins were trailblazers for the NHL in the Czech Republic when it was still part of communist Czechoslovakia, drafting Jaromir Jagr fifth overall in 1990. Though he was definitely #1 prospect material, other teams were concerned about the red tape that possibly needed to be untangled to bring Jagr to Pittsburgh. But he came immediately and nine years later, the Penguins were the first NHL team to have seven Czech players on their roster, with four of them ranking in the top-5 of team scoring. The following season, 2000-01, the Pens became the first team to have 11 Czechs on the roster as they stretched their consecutive playoff streak to 11 seasons.

Today, the NHL is more global in scope than ever before. From 2008-2017, for the first time ever, the majority of NHL players (50.9%) originated from outside Canada. Over one-quarter were non-North American while just under one-quarter were U.S.-born. The high quality of the U.S. National Team Development Program and U.S. college hockey – an area the Penguins heavily scrutinize – shows that the training Jake Guentzel, Bryan Rust and Brian Dumoulin received, is as good as anywhere in the world.

* * *

But what about the next 100 years of hockey? Where will new hockey talent come from?

The nation of 23-million people (approximately the population of Florida) is well-known as a warm weather, sports-loving country. Sydney hosted the 2000 Summer Olympics and Australia is a top nation in swimming, cricket and rugby while producing several NBA, NFL and MLB players. But a country whose climate is more conducive to beach volleyball than hockey only has 2,596 registered senior-level players, just 19 indoor rinks and zero outdoor rinks nationwide, a ratio of 1 rink per 137 players. (By comparison, there is 1 rink per 62 players in the U.S.). While the Australian Ice Hockey League recently announced $18-million (U.S.) in funding to help build new rinks or renovate current arenas, Walker stated his first introduction to hockey was on in-line skates.

If his experience sounds familiar to something closer to home, then you would be correct to think of California. More than funding or a domestic professional league, nothing inspires kids to pursue hockey more than either seeing one of your own make it at the top level or seeing a superstar come to town. We’ve all heard the stories about how a generation of Sun Belt kids took up hockey – first on roller skates, then on ice skates – when Wayne Gretzky was dealt to the Los Angeles Kings. Walker is by no means equal to Gretzky, but his proud representation of Australia at the highest level could pave the way for more Australian kids to pick up a stick and puck rather than other traditional sporting equipment.

* * *

History will show that the NHL sat out the Winter Olympics in PyeongChang this season, but technically, the league did go to Asia this season. It wasn’t South Korea, but Beijing and Shanghai last month, for the two-game 2017 NHL China Games exhibition between the Kings and Canucks. Despite the standard, scripted rhetoric about “growing the game”, going to China comes down to common sense. Or common cents, and dollars. It’s been long overdue for the NHL to stage games in the world’s most populous nation and market hockey to one of the world’s largest economies. Like Australians, the Chinese love sports. Beijing astonished the world with its ultra-modern venues and stunning opening ceremonies when it hosted the 2008 Summer Olympics and will host the 2022 Winter Olympics.

#Canucks have signed Chinese goaltender Zehao (Taylor) Sun to an amateur tryout contract for the NHL China games. pic.twitter.com/ztOi19Grpm

— Vancouver Canucks (@Canucks) September 18, 2017

As the NHL moves into its next century, the league will continue to excite fans all over the globe. In nations like China where participation in the sport only has a small footprint, bringing NHL players to the 2022 Winter Olympics will be a minimum marketing tool. In China, where the TV audience for Game 1 of the 2017 Stanley Cup Final was 22-million, seeing a Chinese-born NHL player one day would bring viewership to untold heights and continue to advance hockey’s profile globally.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!