![]()

William Van Winkle Wolf, was better known in his playing days as Jimmy Wolf or “Chicken” Wolf – a nickname given by childhood friend Pete Browning. He was a mainstay of the Louisville Eclipse/Colonels during their time in the American Association.

The American Association lasted ten years as a competing league to the National League. Wolf is the only man who played in the AA for its entire ten-year run.

He came up as a 19-year-old for the Eclipse (later known as the Colonels), along with other local players like Browning and the Reccius brothers, Phil and John. Wolf primarily played right field in his career, but he also played a few games in every other position on the field as well. He was a steady player his entire career, hitting over .290 in five seasons, and he rarely took a day off. Twice he led the AA in games played, and this was an era where the game was extremely rough on its players. Wolf even stepped up to manage the Colonels for 65 games in 1889, when personality conflicts wreaked havoc on the team. He went 14-51 as the second of four managers the team was to have that season.

Wolf’s best season was 1890, when Browning had bolted the team for the new Players League. Wolf led the AA in batting average (.363) and hits (197) and stole a career-high 46 bases. He led the Colonels to the AA championship and then hit .360 in a postseason series against the National League’s Brooklyn Bridegrooms. His worst season followed immediately after, as he hit just .256 in what was to be the last season of the AA.

The outfielder joined up with the St. Louis Browns in 1892 and did well in his first game but struggled after that. After two poor games, he asked Browns owner Chris von der Ahe for his release. Those three games are the only ones he played in the National League. His lifetime stats include 1,439 hits for a .290 batting average, 18 home runs, 592 RBI and 186 stolen bases. He stole more bases than that, but stolen base totals from his first four seasons are incomplete.

Wolf was an above average right fielder, but he deserves credit for having to share the outfield with Pete Browning, considered to be one of the worst fielders of the era. Al Maul recalled a game where he knocked a base hit into the outfield on a rainy day in Louisville, and the ball landed in a puddle. Browning, closest to the ball, refused to get wet and retrieve it. Wolf rushed over and suggested looking for a stick to fish the ball out of the puddle. As they argued over who would fetch it, Maul ran around the bases for an inside-the-park home run. One of the Louisville coaches handed the outfielders a pair of dice after the game. Should that occasion ever happen again, the coach said, the two were to roll the dice, and the man with the high number would have to wade in after the ball.

Wolf spent a couple seasons in minor leagues up and down the East Coast and worked some as an umpire as well, but he eventually returned home to Louisville and became a fireman. A newspaper report from 1898 detailed a baseball game between the Louisville fire department and the John C. Lewis nine. The firemen won on a clutch three-run homer by Jimmy Wolf himself, whose teammates carried him off the field in celebration.

Stop reading now if you want to believe there’s a happy ending.

On March 8, Louisville Engine Co. No. 12 responded to a fire, with Jimmy Wolf as the driver. A cart owned by the Frank A. Menne Candy Co. was crossing the road at 18th and Chestnut at the same time the fire wagon was heading for the intersection. The two vehicles collided, shattering the wagon’s doubletree, which connected the horses to the wagon. The fire horses bolted ahead, dragging Wolf from his seat onto the cobblestone street and leaving him with a serious head injury. Soon after, be became subject to bouts of “melancholia,” which only worsened when his young son died shortly after his accident.

By July 12, Wolf had been declared legally insane and was placed in the care of his family. By August 3, he was judged to be “not easily controlled” and was placed in Lakeland Asylum – the same one Browning was sent to when his own mental health declined, in fact.

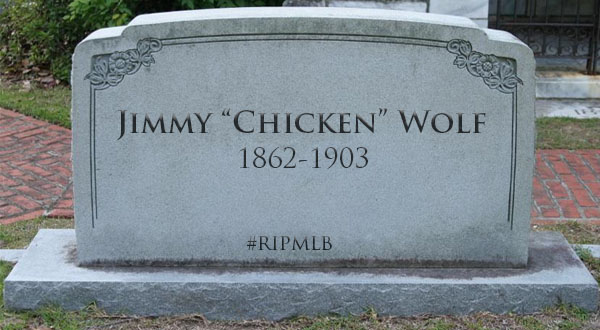

Jimmy Wolf was committed for most of the rest of his life and went to live in his mother’s house upon his release. Not long after, he was hospitalized and died from paresis on May 16, 1903, four days after his 41st birthday. He is buried at Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville, Kentucky.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sam Gazdziak writes about baseball-related gravesites and baseball deaths on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!