![]()

If Harry Stovey is remembered these days, it’s probably for his home run prowess. He was much more than just an early baseball slugger, however.

Read any article written by someone who witnessed Stovey play, and the first thing that’s mentioned is his daring on the basepaths and his ability to steal any base at will. Somehow, this 19th-Century combination of Ruth and Cobb has been overlooked by the Hall of Fame.

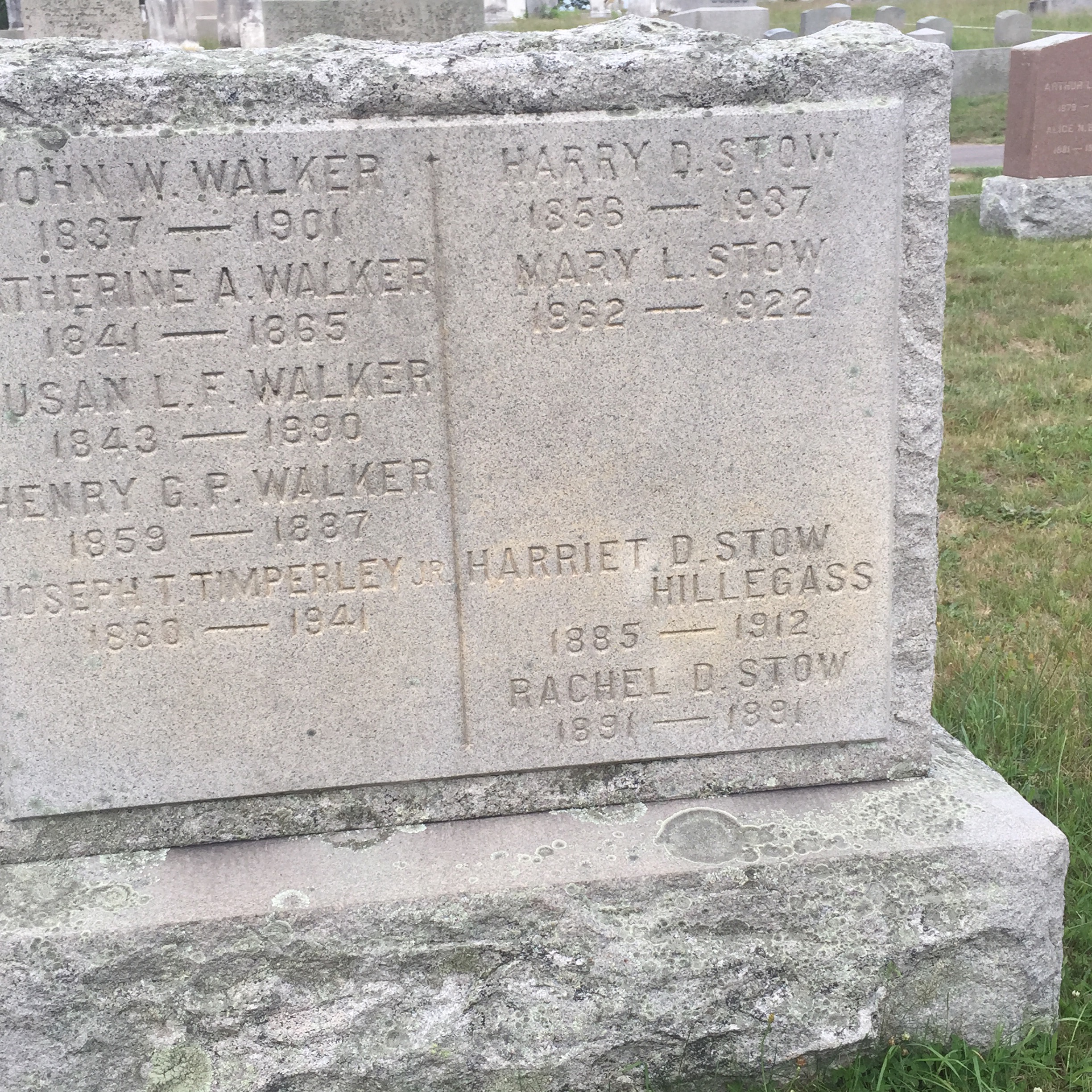

Stovey’s given name is Harry Duffield Stow. He went by “Stovey” during his playing days because baseball players were held in such contempt that he didn’t want to bring shame to his family.

He split his 14-year career in three different leagues, with six seasons in the National League, seven in the American Association and one in the Players League. His .302 career batting average in the AA is almost 40 points higher than his National League average (.265), hurting his Hall of Fame case among those who consider the AA to be an inferior league.

The outfielder/first baseman was a sensation starting from his rookie year, when he broke in with the Worcester Ruby Legs in 1880 and led the senior circuit in triples (14) and home runs (six). His batting average was a low .265, but he never hit lower than .270 over the next eleven seasons and topped .300 four times. Stovey jumped to the American Association in 1883, where he was a mainstay of the Philadelphia Athletics for the next seven seasons. His 29 WAR with the A’s is the most of any player in the team’s nine-year run.

Stovey led the AA in homers three times, with a high of 19 in 1889. He also led in triples three times, doubles once and RBIs once. He was the first man to top the century mark when he clubbed his 100th home run in 1889. He retired after 1893 with a record 122 career homers. That number was eclipsed a couple years later by Roger Connor, who took over the record with 138 round-trippers until a guy named Ruth came along a few decades later.

The Philadelphia native’s most noteworthy accomplishment may have come in 1888, when it was widely reported that he stole 156 bases in 130 games. Officially, he is credited with 87, using modern stolen base rules. For his career, Stovey stole 509 bases, which ranks him 35th all-time. What makes that number even more impressive is that the first six years of his career have no available stolen base stats. It’s not beyond reason that his actual career numbers would place him in the top ten all-time.

Stovey’s base-stealing success was due in part to his sliding technique. He was one of the first players to slide feet first, stiffening his legs as he hit the base so that he popped up straight to his feet on impact. He stole so many bases and tore up his hips from sliding that he invented sliding pads to help cushion the blows.

Even his outs were noteworthy. In one game in 1887 (or 1888), Stovey stepped up to the plate against Ed Beaten with the bases loaded. On an 0-2 count, he swung early at a Beaten slowball, then reared back and swung again at the same pitch, lining a single up the middle. Of course, he’d already struck out at that point, but how many people can lay claim to getting a hit on an 0-3 count?

After hanging up his spikes and sliding pads after 48 games with Brooklyn in 1893, Stovey settled down in New Bedford, Mass. He went back to his original name of Harry Stow and joined the police department in 1895. In 1901, Officer Stow saved the life of a drowning seven-year-old boy at the city’s waterfront by jumping into the water and pulling him to safety. He rose to the rank of captain until failing health forced him into retirement in 1923.

Harry Stovey died on September 20, 1937 at the age of 80. He is buried in Oak Grove Cemetery in New Bedford — just don’t look for a stone marked “Stovey.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Sam Gazdziak writes about baseball-related gravesites and baseball deaths on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!