You know you’re in the first full month of the Penguins offseason when all anyone is talking about is the impact of potentially trading Evgeni Malkin.

Why should anything be different this year?

By now, you’ve probably heard it all.

“Malkin had a bad year.”

“GMJR won’t commit to not trading Malkin.”

“Malkin’s not the player he once was.”

“Malkin is a bad teammate.”

https://twitter.com/G_Off817/status/1120678783424528384

Much of this super-nuanced discussion has come without the acknowledgment that neither Lemieux nor Malkin want to see Malkin traded and that Malkin has a full NMC.

But let’s not get bogged down with those details and instead ask ourselves this: how bad of a year did Malkin really have after finishing with 21 goals, 51 assists and 72 points from 68 games?

Let’s break it down into 3 segments: his individual production, his plus/minus, and his possession metrics.

All data herein provided by NaturalStatTrick.com

Individual Output

First, we have to consider a few things centered around context.

The first thing the Trade Brigade™ will point out is his lack of goal scoring this season, which is a reasonably fair thing to look at.

His 21 goals in all situations was his worst output of his career in seasons where he played 50+ games. He scored 15 in 43 games in 2010-11 (the year he tore his ACL) and just 9 in 31 during the lockout-shortened season as his true career lows.

Those years, he was also victimized by career-low shooting percentages (8.2% and 9.1% respectively).

This year, as you might imagine, saw a similar trend. He shot at 11.2% this season, a full 2.4 percentage points below his career average of 13.6%. If Malkin shoots at his average, he’s looking at about 25 total goals and 76 points on the year in 68 games. Hardly seems bad for a guy one year removed from finishing 7th in Hart voting, right?

Furthermore, on top of his all-situations shooting percentage taking a dip from his career average, so too did his 5v5 shooting percentage as you would expect to be the case. This season, Geno saw a 9.32% return on his shots on goal, down from his 13.89% last year and 12.57% career total. That accounts for a loss of roughly 3-4 5-on-5 goals.

And when we look at just what he did at 5v5 this season, we get a better sense at just how fine he actually was compared to his career to date.

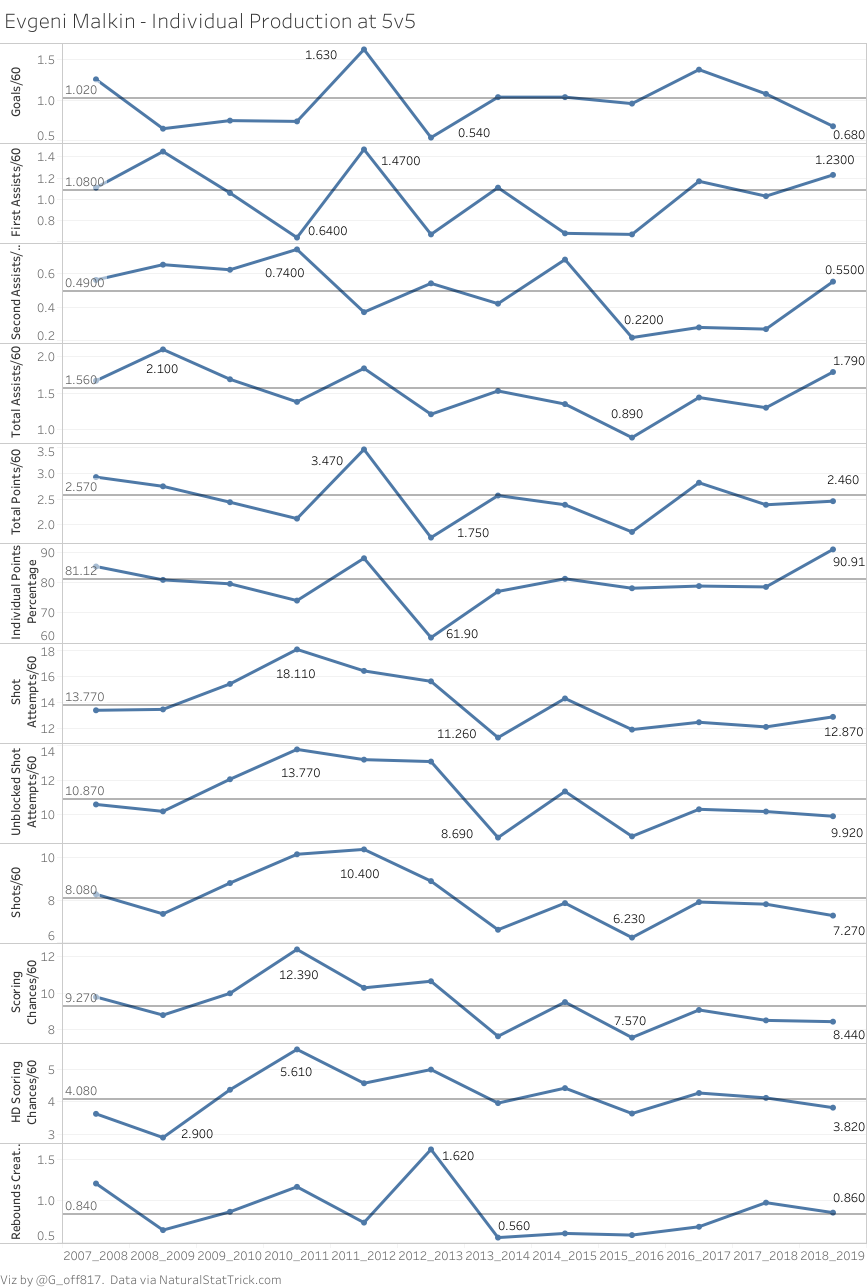

Below, you’ll see a season-by-season representation of Malkin’s individual production in terms of points, individual shot-based metrics, individual scoring chance-based metrics, and Individual Points Percentage (which is simply the percentage of Penguin goals scored while Malkin is on the ice on which he registered a point) per 60 minutes of 5-on-5 ice time with a reference line to illustrate his career average.

What’s worth noting is that Malkin’s 2.46 total 5v5 points per hour of ice time ranked him 32nd in the league this season, just 0.01 behind the likes of Evgeny Kuznetsov (21G-51A-72P in all situations), David Pastrnak (38G-43A-81P in all situations), and Matt Duchene (31G-39A-70P in all situations).

It also ranked him ahead of names like Jonathan Huberdeau (2.45 points per 60), Claude Giroux (2.44 P/60), Jack Eichel (2.43 P/60), Alex Ovechkin (2.39 P/60), Aleksander Barkov (2.3 P/60), Mark Stone (2.29 P/60), Mikko Rantanen (2.17 P/60), and Nathan MacKinnon (2.07 P/60).

Considering only Mark Stone scored fewer than 80 points in all situations out of the 8 players Malkin ranked higher than in 5v5 points per hour of play, it’s hard to imagine why there is so much ax grinding. Contextually, none of the aforementioned players have been said to have had a “bad” or “down” year, yet Malkin is the exception to the rule.

In fact, Malkin’s 40 total 5v5 points this year was his 3rd best return since the 2013 lockout-shortened season, just behind his 41 in 2016-17 and 44 last season, while his 29 total 5v5 assists and 20 primary assists were his 4th best returns of his career and best post-lockout outputs.

So, while Malkin shot the puck slightly less this season as he generated just under 1 fewer of each of shot attempts, unblocked attempts, shots on goal, and scoring chance (plus right around the same HD scoring chance) versus his career average per hour of 5v5 play, the puck also didn’t want to go in for him either.

But he found himself well above his career average across all assist buckets while factoring in on 90.91% of the goals scored while he was on the ice at 5v5.

To put that in perspective, that 90.91% was the fifth most among NHL players that played 300+ minutes this season, while his 40 points was most among the top 10 in the IPP category.

TL;DR: It shouldn’t matter who scores the goals, as long as goals are being scored.

And for Malkin, that came in the form of a 1.79 total assists per hour, 7th best in the league, and an 8th-best 1.23 primary assists per hour of 5v5 play.

That hardly seems a bad season.

Plus/Minus

The other problematic statistic thrown out to illustrate how rough Malkin had it this season is his tumultuous plus/minus, which saw him put up a career worst -25. This is, however, a very skewed data point to point to when you consider the scenarios in which these minuses occurred (while ignoring how bad of a data bucket +/- actually is, which will hopefully be illustrated below).

Consider this: at 5v5 this season, Malkin was on the ice for 44 goals for and 46 against, a differential of -2. In all even-strength situations, that jumps to 51 for and 64 against (-13) while also being on the ice for 12 shorthanded goals against. There’s your -25.

So, it stands to reason that it was non-5v5 even strength (i.e. 4v4, 3v3, and pulled goalie scenarios) as well as the powerplay that were the sources of Malkin’s “defensive issues” (i.e. goals against).

Out of his 1278:40 total time on ice, 220:25 came at 5v4 and 67:24 came at non-5v5 even-strength, including the 28:01 that came with the Penguins’ net empty (where they were outscored 11-1 with Malkin on the ice, -10) and 8:22 against an opponent’s empty net (Penguins outscored opposition 4-3 with Malkin on the ice there, +1).

https://twitter.com/G_Off817/status/1125396139803652097

That means, conservatively, we’re talking about Malkin’s season being defined by under 300 minutes and less than 25% of his total ice time, where -9 of his -25 came while a net was empty and -12 more came on a 5v4 powerplay.

In other words, -21 of his -25 came from situations where one team had more skaters on the ice than the other.

Considering the Penguins have given up 10+ shorthanded goals against with Malkin on the ice just 2 other times in his career and have never seen more than a -6 differential with their net empty while he’s on the ice, it’s hard to imagine a -22 differential ever being replicated simultaneously in a single season ever again for Geno, let alone the Penguins as a team.

It was, for all intents and purposes, the perfect storm of weirdness.

On-Ice Possession Metrics

Finally, let’s take a look a the process that yielded these results while entertaining the question as to why the powerplay and empty net minuses didn’t impact the likes of Crosby and Letang overall in the same way they impacted Malkin; despite Crosby and Letang having also been on the ice for many of those events.

It starts and ends with whom Crosby saw his ice time and what he did with that ice time. Because for Crosby and his 1253:16 of 5v5 ice time, he spent almost exactly half of it with Kris Letang. Together, they were on the ice for 45 goals for and just 18 against out of the 82 for and 43 against for Crosby (+39) and 74 for and 47 against for Letang (+27).

In other words, 5v5 play for Crosby and Letang more than made up for they minuses they incurred at 5v4 (-13 for Crosby, -11 for Letang) and with their net empty (-12 for Crosby, -8 for Letang).

So why was it that Malkin (and Kessel, for that matter) didn’t get this same run support as Crosby?

The answer might come as a surprise, but signs largely point to one issue: quality of teammates.

See, while Crosby was hogging up minutes with Letang, it meant the Penguins second pair of Jack Johnson and whomever he played with got the deployment with Geno and the Penguins second line.

And of Malkin’s 974:13 played, 365:43 came with Jack Johnson, more than any other Penguins defenseman and second-most among Penguins skaters behind the 637:57 Geno played with Phil Kessel. That accounts for just under 38% of Malkin’s ice time being spent with Jack Johnson, who is discernibly not Kris Letang.

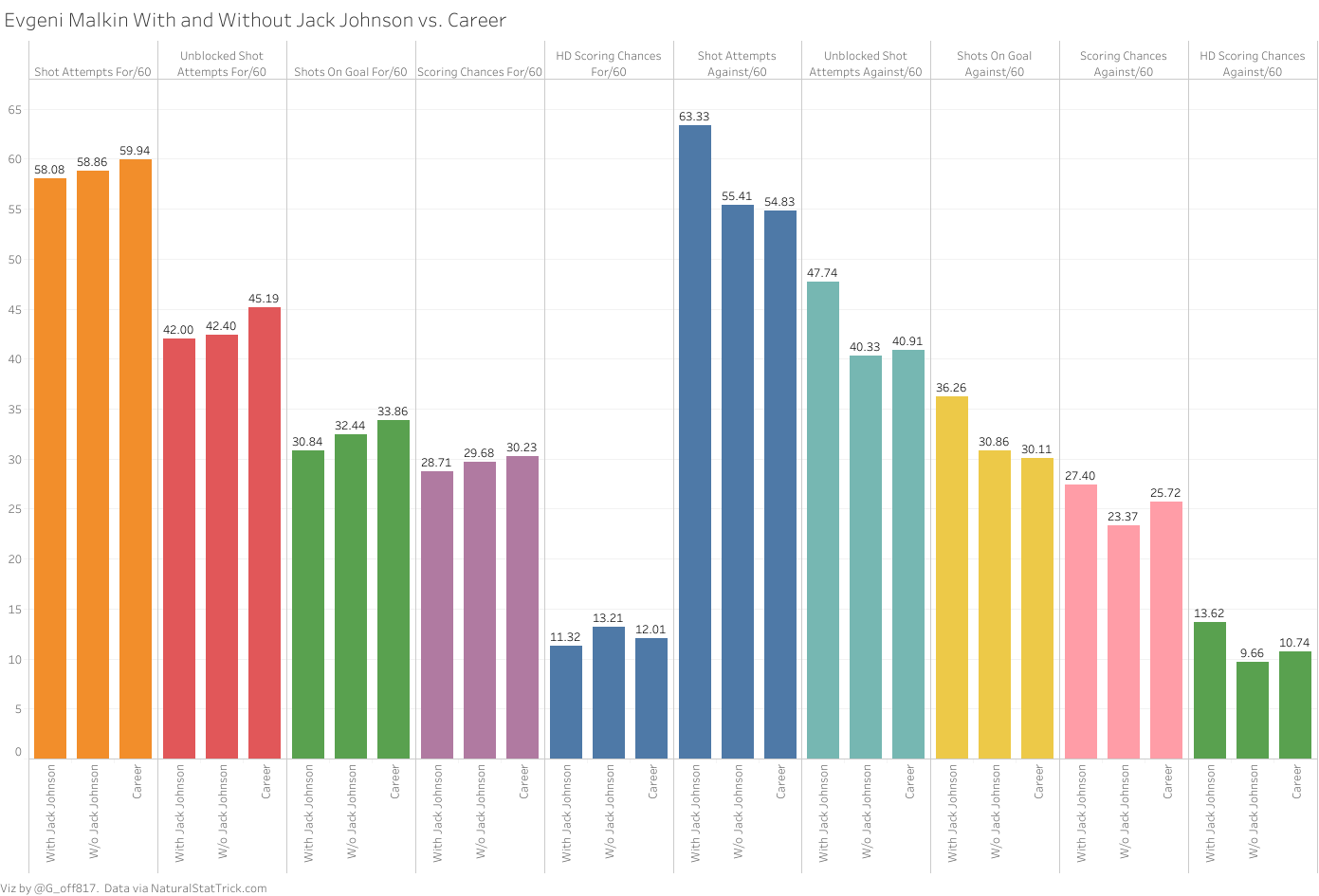

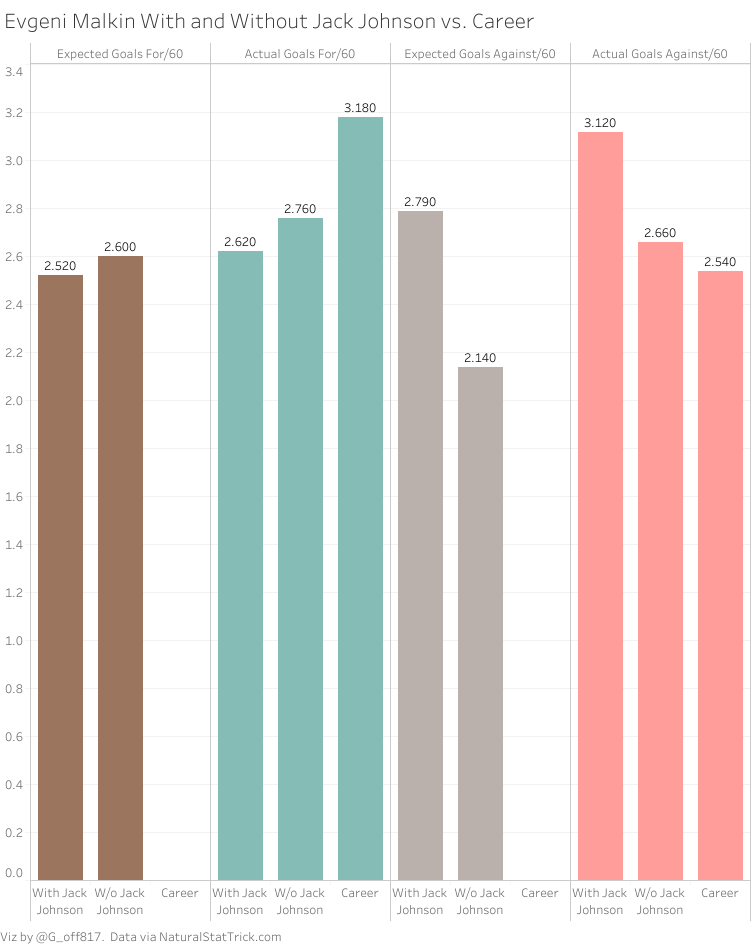

The results were staggering (Note: Natural Stat Trick does not have career Expected Goals values, so bear with me on those):

As it turns out, when Malkin was on the ice without Jack Johnson this season, shot-based and scoring chance-based metrics, for and against as well as his percent shares, were all relatively close to that of his career averages.

The same can be said about his goals against, though he did see a slight uptick in his actual goals away from Johnson despite scoring nearly half a goal fewer per hour of ice time away from 73 compared to his career average. Again, shooting luck was not on Malkin’s side this year, who has a career on-ice shooting percentage of 9.45% vs. the 8.51% this season.

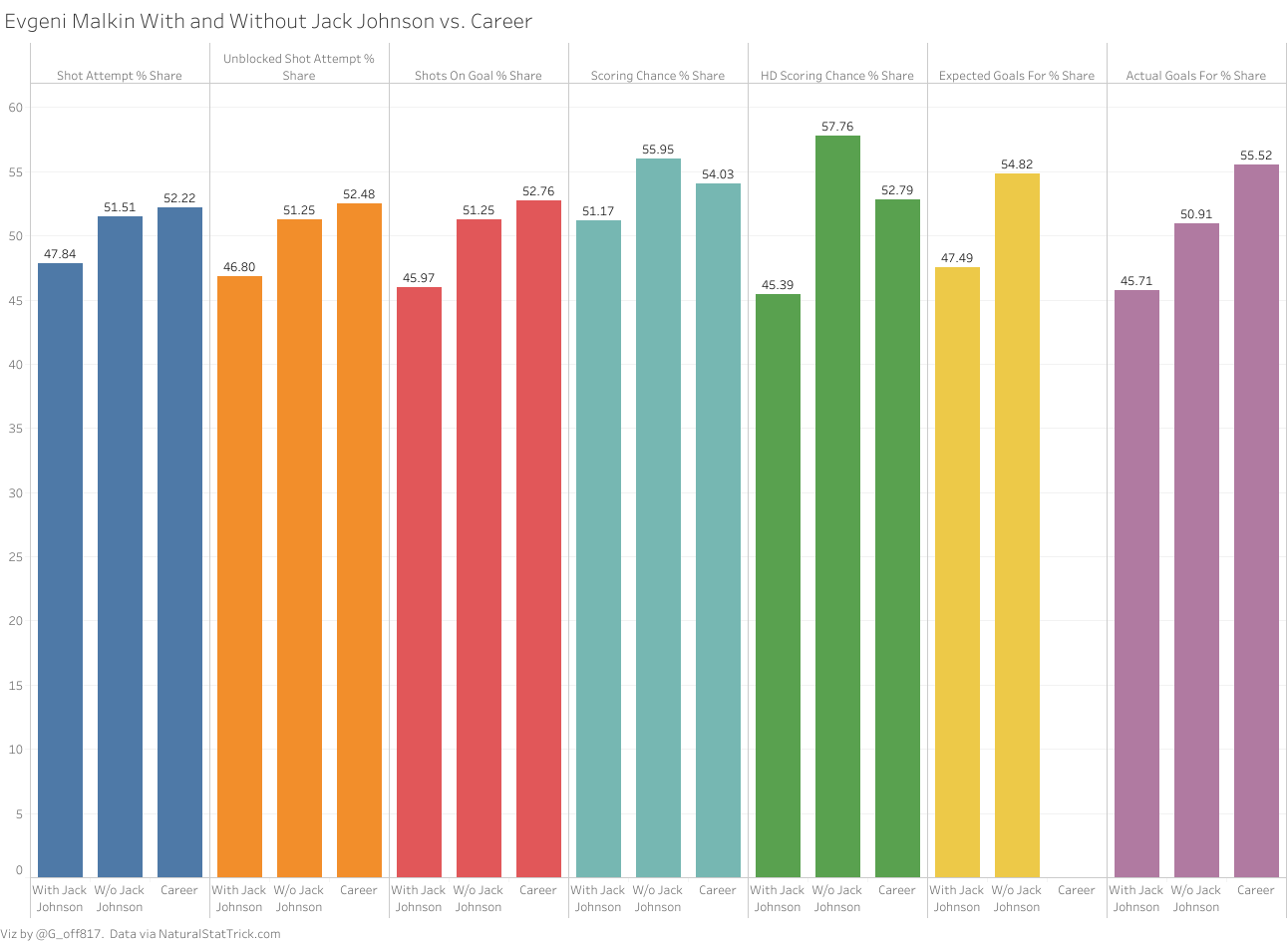

The big takeaway, though, is just how limited by Johnson Malkin actually was. Because, while Malkin did push the puck in a positive direction at about the same clip with and without Johnson, it’s the amount of “against” events per hour that is a problem, skewing his overall share of the above data buckets:

Again, across the board Malkin saw a 50%+ share of every single metric when away from Johnson compared to the sub-50% share with Johnson.

In other words, when Malkin was on the ice without Johnson, the Penguins controlled the events that took place and lived more in the offensive zone.

Conversely, when Malkin and Johnson were on the ice together, the majority of the events that took place were in the Penguins end of the ice.

Think of it this way: if teams are hammering Malkin with more shots and scoring chances when he’s on the ice with Johnson than the Penguins are generating, it means that Malkin is likely spending more time in his defensive zone than in the offensive zone.

Put another way, Malkin and his teammates are going to have a harder time scoring goals, an event that almost exclusively takes place in the offensive zone, when they are spending their time getting smoked in their own end.

That is not a recipe for success.

The end result when all of these factors are combined together inevitably will lead one to believe Evgeni Malkin had a bad season when, in reality, it can largely be chalked up to the variability that comes with scoring goals in this league, some bad luck in typically advantageous in-game scenarios, and some good, ol’ fashioned poor deployment.

The obvious solution is twofold:

1) Keep Jack Johnson away from Evgeni Malkin and Phil Kessel (and everyone else on the team, for that matter) and see if that doesn’t fix Malkin and, more importantly;

2) try not to do anything rash by trading away one of the top 101 players of all time and instead let regression sink its teeth in.

After all, what GM really wants to be the guy that puts “traded a 3 time Cup winner, 2 time scoring champion, and a Hart and Conn Smythe winner” on his resume?

Because when you trade Evgeni Malkin, you not only lose Evgeni Malkin (and the trade itself in all likelihood), but you give Evgeni Malkin to another team.

That’s a dangerous proposition.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!