The Major League Baseball Line-up Redesigned: The Mobius Strip Theory

In 2010 I devised and introduced the Mobius Strip Theory for MLB hitting line-ups, which presented a radical alternative to baseball’s traditional batting order template.

I thought it would be interesting to apply the Mobius Strip Theory to the San Francisco Giants 2014 batting line-up (below), and continue the discussion.

The traditional batting line-up may be one of the final untouchable strategic institutions inside the modern game.

Baseball’s offensive attack should be based on which configuration of hitters can potentially produce the highest number of runs in any given game; and average the most runs per game over a 162 game season.

In 2010 John Russell was about to start his third year as the Manager of the Pittsburgh Pirates. I wouldn’t really call Russell’s first two seasons in Pittsburgh “disastrous”… I think “catastrophic” is a much more accurate description: 62-99 in 2009, 67-95 in 2008.

So Russell decided to take a page from Tony La Russa’s playbook and at the end of Spring Training 2010, he announced that Pirate pitchers would bat 8th in the batting order throughout the entire season.

The idea was to generate more runs by adding the classic “second lead-off” hitter to the batting line-up. In this case shortstop Ronnie Cedeno batted in the 9th position, so when clean-up hitter Garrett Jones later walked up to the plate he might just find someone else on the field besides the opposition defense.

In the conservative world of baseball management even this modest experiment is the equivalent of going from analog to digital, or cutting rare steak from your diet and adding more fiber.

And if there’s one thing that the Major League Baseball establishment needs a lot more of, it’s fiber.

This fascinating subject is on the table only because La Russa, once an innovator, first batted his pitcher in the eighth slot of the order in 1998, his third year as manager of the St. Louis Cardinals.

La Russa stated that during his tenure as an American League manager with the DH, he was convinced that a “second lead-off” man batting ninth provided more opportunities for his number 3 and 4 batters to drive in runs.

Typically, the MLB establishment was out buying a corndog at the concession stands when this issue first came up, leaving the baseball saber and statistical community to crunch the numbers and properly analyze the phenomenon. And, as usual, they came through.

Specifically “The Book: Playing the Percentages in Baseball” by Tom Tango, Mitchel Lichtman, and Andrew Dolphin, researcher David Pinto, the legendary Cyril Morong and a number of other great researchers have thoroughly examined the impact of batting a position player 9th in the batting order (among other batting order scenarios).

The hard research seems to point to a modest advantage for National League teams who hit their pitcher 8th: an increase from 4.50 runs per game to 4.59 runs per game.

That’s about 14.5 runs a year, which results in maybe two additional wins a year.

Thirty years ago authors Peter Palmer and John Thorn, in their classic book “The Hidden Game of Baseball”, determined that a team’s best hitter, rather than batting third in the order, should hit second. So in 2010 Bucs Manager Russell had his best hitter, center fielder Andrew McCutchen, bat in the two hole in the Pirate’s line-up.

It turns out the 2010 season didn’t work out well for Manager John Russell as ownership and media pressure forced him to slowly abandon his tinkering with the Pirates line-up. So we really don’t have a full season model to analyze.

But five or ten years from now Russell and La Russa may be seen as pioneering innovators in the redesign of the game’s batting line-up.

The Linear Line-up

The traditional MLB batting lineup has always been seen as an up and down list of players with set offensive attributes that form a straight, one dimensional line to produce runs. Let’s call it the Linear Line-up.

The Linear Line-up is viewed as continually starting and stopping, from lead-off to 9th in the order and then back again over and over. To accommodate this idea of a predictably recurring batting order, set roles have been historically assigned to each spot on the Linear Lineup which are supposed to define and drive the offense:

> the lead-off man has a good on base percentage, little power, and is a fast runner;

> the second hitter is a bat handler who can “move” the lead-off batter around the bases;

> the number three hitter is the best “pure” hitter in the line-up;

> the four hitter has the most power and is the primary RBI guy;

> the #5 hitter is the second best RBI power hitter;

> the #6 hitter has occasional power;

> the 7th, 8th, and 9th batters are, respectively, the worst hitters in the batting order.

But as research refines tradition, there is little about the performance aspects of Major League Baseball that hasn’t been examined by a generation of analytic baseball scientists. We are way overdue for an medically intrusive examination of the traditional Linear Line-up.

Let me emphasize that the goal of any hitting lineup analysis is to answer one question: how can a team restructure its batting order to create more runs? That is, how can a team put more runners on base so their best hitters can produce runs? And how can they develop more offensive opportunities per game to maximize the offensive situations that develop each game?

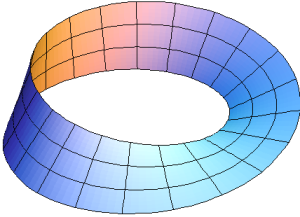

The Mobius Strip Theory

The instant the first pitch of a baseball game is tossed, the batting lineup, rather than being the repeating linear list we are all familiar with, actually becomes an unending circular directory without beginnings or endings.

As the cliche goes, baseb

So a winning team not only needs to be able to maximize possible offensive opportunities whenever they come up each game, that team also needs to proactively create those opportunities.

Thinking of the MLB batting order as a circular directory of hitters means reevaluating the traditional line-up. Finding the correct location and orientation for the most accomplished batters is now logically best served by having them centered inside the ongoing directory, separated as far as possible from non-producing batters.

A Mobius strip has the mathematical property of being non-orienting, meaning (after the first inning) there is no starting point or stopping point, only one side and only one boundary. The analogy to a baseball batting order is that, over the broad course of each game, there is no lead-off batter and no number 9 batter– there is only a continually looping directory of players in random order depending on the location of outs made each inning.

Here is a condensed summary of the Mobius strip theory.

The three best hitters on a team bat 1 through 3 in the line-up, with the “best” hitter batting second. That would be either the traditional #3 or #4 batter.

The 8th and 9th batters in the line-up would be the next two best hitters on the team. The players who contribute least to the offense, typically the pitcher and position players known more for their defensive skills (catchers, etc.), are separated from the 1-3 hitters equally from either end of the lineup.

The central point here is to give the best run-producing hitters in a team’s line-up the most opportunities to create runs by insulating them as much as possible in the batting order from the least productive hitters in a team’s line-up. For as many innings as possible.

Here’s how the projected 2014 San Francisco Giants lineup looks using conventionally accepted linear batting order criteria:

- Angel Pagan – CF Good OBP, fast runner, moves around bases well.

- Marco Scutaro – 2B Contact hitter, moves lead-off batter into scoring position, great bat control.

- Brandon Belt – 1B Best young hitter on the team, high OBP, emerging power.

- Buster Posey – C Cleanup hitter; best pure power hitter on a team without power, RBI leader

- Pablo Sandoval – 3B Second best power hitter on team, “protects” #4 batter, second RBI leader.

- Hunter Pence – RF Extra base hit power, RBI producer.

- Michael Morse – LF More likely to create outs, occasional power.

- Brandon Crawford – SS Contact hitter, possibly on base for top of the order, best spot in lineup for defensive players.

- Pitcher – National League pitcher slot. Often American League “second lead-off” man spot.

And here’s how the same 2014 Giants lineup would look in a Mobius batting order configuration:

- Marco Scutaro – 2B Second or third best pure hitter on the team.

- Buster Posey – C Best hitter on the team (the #3 batter in most linear lineups).

- Pablo Sandoval – 3B Second or third best pure hitter on the team.

- Hunter Pence – RF First of two players with extra base hit potential, but lower OPS.

- Michael Morse – LF Extra base hit potential, more likely to create outs.

- Brandon Crawford – SS Second most likely hitter to create outs in the continuing directory of batters.

- Pitcher – Most likely to create outs in the continuing directory of batters.

- Brandon Belt – 1B Good OBP, fourth or fifth best hitter on the team.

- Angel Pagan – CF Good OBP, fourth or fifth best hitter on the team.

Not only do the statistically best hitters, assigned 1-3 in the batting order, receive the most at-bats, the best hitter on the team (batting #2) will have the three batting order positions in front of him filled by the second or third best hitter on the team, and the fourth and fifth best hitters on the team.

Which creates an ongoing run-producing dynamic for nine innings.

Each ballgame “artificially” starts with the #1 hitter at the plate, in the example above it’s Marco Scutaro. But after the pitcher’s #7 spot is passed the first time around in the order, the lineup becomes the continuing directory of a Mobius strip with the three best hitters up more often, and two quality hitters batting in front of those three players for the rest of the game.

The Mobius Theory puts the hitters most likely to create outs as far away as possible from the top three hitters in the lineup tasked with creating runs throughout the game.

Several sidebar issues

First, “moneyball” considerations.

Specific player on-base percentages, the ability to make contact with the ball and scoring runs without pounding out 45 home runs, etc. are as workable as any other definition of what a “preferred” hitter might be.

Each general manager and manager would still determine the criteria of what constitutes a “good hitter” based on the players they have available and the opposing pitcher being faced on any given day.

Primary placement in a Mobius Strip lineup can include such considerations as which players are the best contact hitters, which hitters take a lot of pitches, and which players are most adept at moving around the bases, etc.

The manager still has the primary responsibility to put the right players inside the Mobius Strip lineup configuration, which would include platoons and the best hitter-pitcher match-ups.

Second, pinch hitters are routinely used in National League games in the late innings to replace the pitcher or poor performing regulars. Their entry late into a game adds to the overall effect of a Mobius line-up when it’s needed most– replacing poor performing regulars with better performing bench players.

Obviously player talent level is relative for each team: the object here is to look at the concept, not at individual player names (or how much better or worse those players are now than in 2014).

Obviously each team has to work with the 25 man roster they have. But in fact, a Mobius Strip line-up works with all levels of teams.

Having proposed the Mobius Strip Theory, it is important to note that professional sabermetricians (whose knowledge certainly exceeds my own) have conducted countless scenarios which consist of placing different categories of hitters in different slots in the batting order to see how run production might be affected.

So far, although no agreed upon “perfect” lineup has emerged, a great deal of interesting and valuable information has been developed. Some amount of this research runs contrary to the Mobius Theory. For example, some scenarios show batting the pitcher 8th in the order can increase runs scored, while batting the pitcher 7th does not.

As the corners of baseball’s sabermetric universe continue to be explored and expanded, the everyday batting lineup should always be a focal point of discussion and theory. And that’s the first step in challenging unexamined practices and creating new models to achieve success.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!