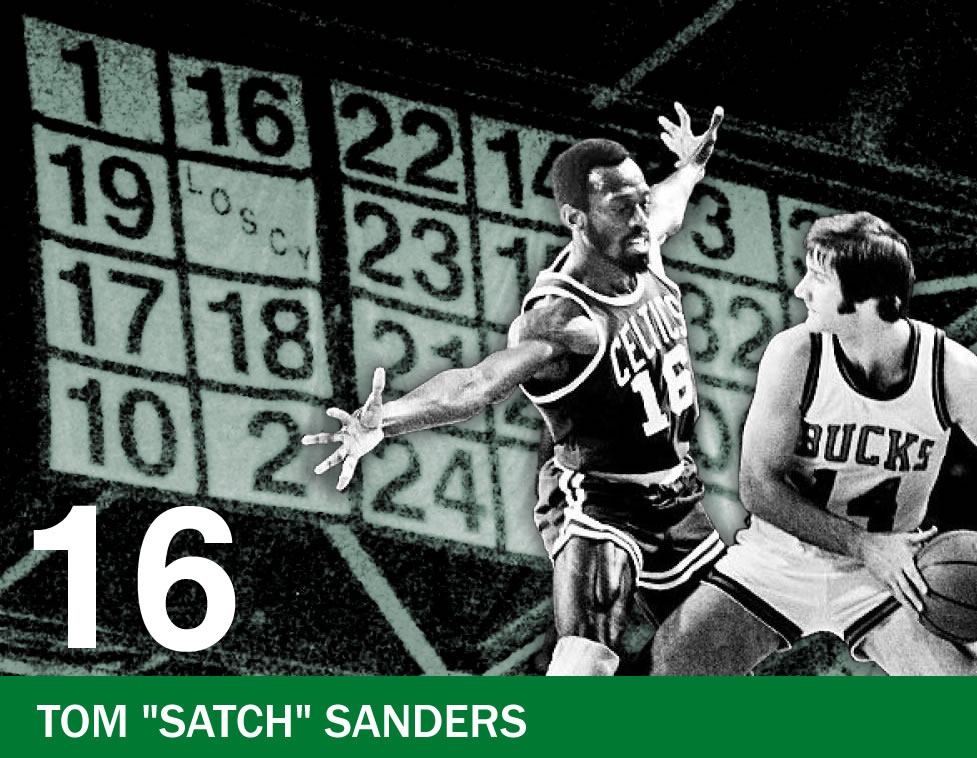

From now until February 11, Red’s Army will be posting stories about the players behind the Celtics’ 22 retired numbers and that one retired nickname. Stories will be posted in the order that the numbers were retired.

If you’re a guy who likes to judge players based on box scores, you’d best skip this article entirely. All it’s going to do is irritate you and leave you citing Satch’s meager PPG totals and speculating that the Celtics have retired too many numbers. Not even ten points per game!

Basketball is, quite easily, the highest scoring professional sport. It is also the only sport that does not have defensive positions.

(It did, once upon a time–‘guards’ were called such because they were expected to ‘guard’ their basket and prevent the other team from advancing the ball past half-court, sort of like a defenseman in hockey)

Even today, in the era of advanced stats, assessing defensive impact is difficult to do using numbers alone.

But the thing about Red and Russell’s Celtics is that they only cared about one stat.

Wins.

It’s a trite observation that the object of the game is to score more points than your opponent. Red’s Celtics were dominant in part because half his players were tasked with scoring and the other half were tasked with defense. In an era where defense was barely understood (Bill Russell used to get dinged by his college coach for jumping, because defenders were supposed to stay flat footed), Red put guys on the court whose job was to make the other team’s best players miserable.

And that brings us to Satch.

Satch was the second player from New York City’s street ball scene to make an impact with the Celtics–Bob Cousy was the first. Satch was born in Harlem, grew up in Harlem, and learned how to play basketball in Harlem. He got his nickname there too.

He was part of the first generation of black players who had a legitimate shot at playing in the NBA–but he learned how to play from veterans of the street ball scene. They had great nicknames, and they could be tough on you. Guys like Tarzan Cooper and Pop Gates hounded the young kids looking to prove themselves at Rucker. If you could take it, you might be able to make something of yourself, and if you couldn’t, well, they were done with you.

When Satch was in his early teens, a couple older friends of his told him that he had a shot at the pros.

Thing is, if Satch wanted to get into the NBA he had to go to a university, and to get to a university he had to attend a traditional high school. And back then, if you made it to junior high in Harlem, your guidance counselor was going to gently–but firmly–steer you toward a vocational high school. Sure, no one was going to stop you from going to college, but, you know, there were just so many more opportunities for, well, people like you, in trades. You wouldn’t want to end up with a degree that would be useless because, well, there aren’t a lot of openings in professional fields for, well, people from around here.

Satch bucked the trend, got into a high school in the Lower East Side, and from there he was accepted into New York University. He took NYU to the Final Four in 1960 (the school has since reclassified to Division III), and was drafted by Red a few months later.

Like Sam Jones, who was easing into Bill Sharman’s role in the two guard spot, Red assessed Satch’s abilities and decided he was going to replace Jim Loscutoff defending the other team’s best wing player.

Jim’s style was, shall we say, appropriate for the times. Satch’s style was different, but the goal was more or less the same.

Make the other guy miserable.

There is an art and an attitude to good defense and Satch had that attitude. Does your man like to drive right? Make him drive left. Not good at shooting from the outside? Make him pick up his dribble a long way from the basket. How close can you get to a guy without getting called for a foul? Start that close and see if you can get away with guarding your man even closer as the game goes on.

Bill Russell and Satch Sanders were the linchpins of Boston’s defense in the 60s. They were the experts in forcing you to play the game the way they wanted you to play it. They got in your heads. They made you think twice about shooting the ball, passing the ball, or driving the lane. They were smart players–you have to be to play good defense. Good offensive players love to exploit defenders that play off of instinct.

With Russ and Satch you had two cerebral guys who knew what you were all about, and they were there to mess it all up.

Satch picked up eight championships playing for the Celtics, without ever producing a season of gaudy stats. Yet–and you can ask anyone who played with him on those teams–there’s no way the Celtics win all those titles without him.

When he retired, he stayed around the Boston area–in fact his first gig after retirement was coaching the Harvard Crimson (he was the first black Ivy League coach).

He had a couple brief fill-in stints coaching the Celtics between the Heinsohn years & the Bird years in the 70s, and in the mid 80s, he got in touch with Richard Lapchick at Northeastern University. Lapchick had just started the Center for the Study of Sport in Society, and Lapchick wanted Satch involved, “In discussing some of the things that I wanted to address, such as student-athlete graduation rates and the lack of opportunities for women and people of color as head coaches and in front office positions in the various professional leagues and at the college level, it was clear that Satch was a deep thinker on these and other issues.”

A couple years later, Satch started a little program designed to help players transitioning into and out of the NBA–helping rookies adjust to the downsides that come along with having your dream come true, and helping players at the end of their careers find stability in a retirement that starts at roughly the same time most of us are just settling into our careers.

David Stern liked Satch’s program and brought him on in 1987 to convert his project into an official league operation–the first of its kind in professional sport.

Satch finally got into the Hall in 2011 (as a ‘contributor’, although he should’ve been inducted as a player as well), and he accepted that belated honor with his trademark bowtie and easygoing nature (this is the guy who told JFK to “take it easy, baby” at a White House ceremony recognizing their ’63 title).

Satch’s misleading career stats at Basketball Reference.

PS: That last video is 45 minutes long, but you should watch it if you’ve got the time. Satch has spent a long lifetime collecting stories and time spent listening to him is not time wasted.

The retired numbers project:

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!