Writer John Dewane of ACTA Sports recently posted MLB defensive shifting numbers (no source noted but I believe Baseball Info Solutions tracks the use of MLB defensive shifting).

Defensive shifts were first fully tracked in 2011, when a handful of teams put them on 2,350 times.

Defensive shifts were first fully tracked in 2011, when a handful of teams put them on 2,350 times.

In 2016 the number of times shifts were used had soared to 28,074.

So far this season we’ve seen defensive shifts used 2,542 times— which projects to nearly 32,000 shifts in 2017.

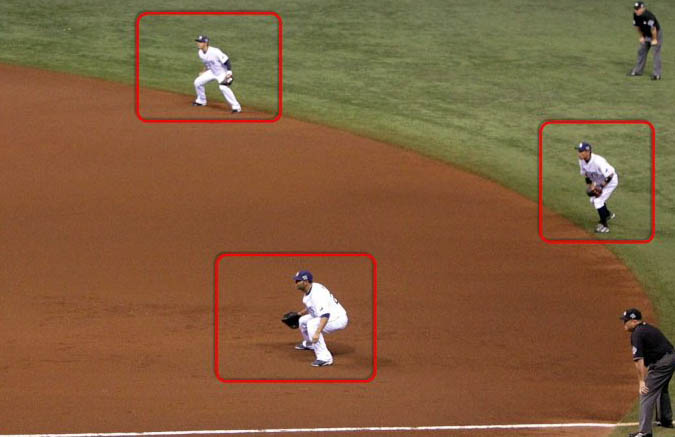

It is amusing to hear information-challenged fans demanding that defensive shifts in the infield be banned by Major League Baseball. (I guess they’re OK with outfielders defensively shifting to the left and right, and in and out).

But it’s really bizarre that anyone who follows the game is still asking the question: do shifts really work?

In 2014 defensive shifts were used 13,299 times and prevented 196 runs— a rate of 67.85 shifts per run saved.

In 2015 17,744 shifts saved 267 runs, or 66.45 shifts per run saved. And in 2016 28,074 defensive shifts saved 359 runs—78.20 S/R.

The idea that thousands of defensive shifts are being used by billion dollar organizations without any data to quantify the results is a reminder of how often fly-by commentators believe their own alternative facts.

Here’s another defensive shifts-related question that needs to go away: why don’t MLB hitters just bunt or hit against the shift to beat it? And then, you know, all that shifting will go away.

The whole idea behind defensive shifts is that teams now have years of data that track every hitter’s every at-bat each season. How individual batters hit righties, lefties, specific pitchers, with runners on base, and so on.

The idea that players who have tirelessly worked since little league to hone their individual hitting skills (skills that are now earning them tens of millions of dollars a year) would casually abandon their power stroke to “go the other way” to beat a defensive shift is delusional.

And guess what? If a defensive shift makes a talented hitter (and at the Major League level they’re all talented) try to bunt instead of hit a home run or double, then the opposing team has successfully diminished your offense.

Finally, a player who routinely abandons his power stroke to beat defensive shifting is also in for a big surprise at contract time. Management will happily point out his alarming decrease in slugging percentage, which will cost that player money.

Why? Because hitters are paid tremendously more money for getting extra base hits and driving in runs than they are for bunting or slapping a single the other way.

On another front, it may seem that over the last several seasons extra base-hitting sluggers are either striking out or hitting home runs. But they are also getting walks. A lot of walks.

Here’s a sampling from 2016: Paul Goldschmidt/Arizona 110 walks; Josh Donaldson/Toronto 109; Bryce Harper/the Nationals 108; Brandon Belt/Giants 104; Carlos Santana/Cleveland 99; and Chris Davis/Baltimore 88 walks.

The term “Three True Outcomes” was popularized in August of 2000 by Baseball Prospectus co-founder Rany Jazayerli in an article about Rob Deer and several other players who embodied the home run/strikeout/walk model.

In 2015, MLB Network analyst Brian Kenny declared the Three True Outcome era was about to deluge the game, led by young sluggers Joc Pederson of the Dodgers, Kris Bryant of the Cubs, and George Springer of Houston among others.

And that has certainly happened.

The impact of players embracing and being highly paid for TTO-style play is that, increasingly, there are fewer balls in play on average per game. Which translates into less “action” and more concern from those who are distressed about pace of play/length of game issues.

Like Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred.

But throughout Major League Baseball’s 141 year history there have been two constants you can absolutely count on.

First, baseball constantly changes. It’s like time-lapse photography of flowers blooming– in real time you can’t see any movement but it’s actually changing all the time.

Second, there will always be traditionalists who insist that baseball should never change, that the way the game is played in [pick any year] is the way it should always be played.

And every year a new MLB season seems to glide and soar effortlessly between those seemingly contradictory constants. Never changing and also moving forward.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!