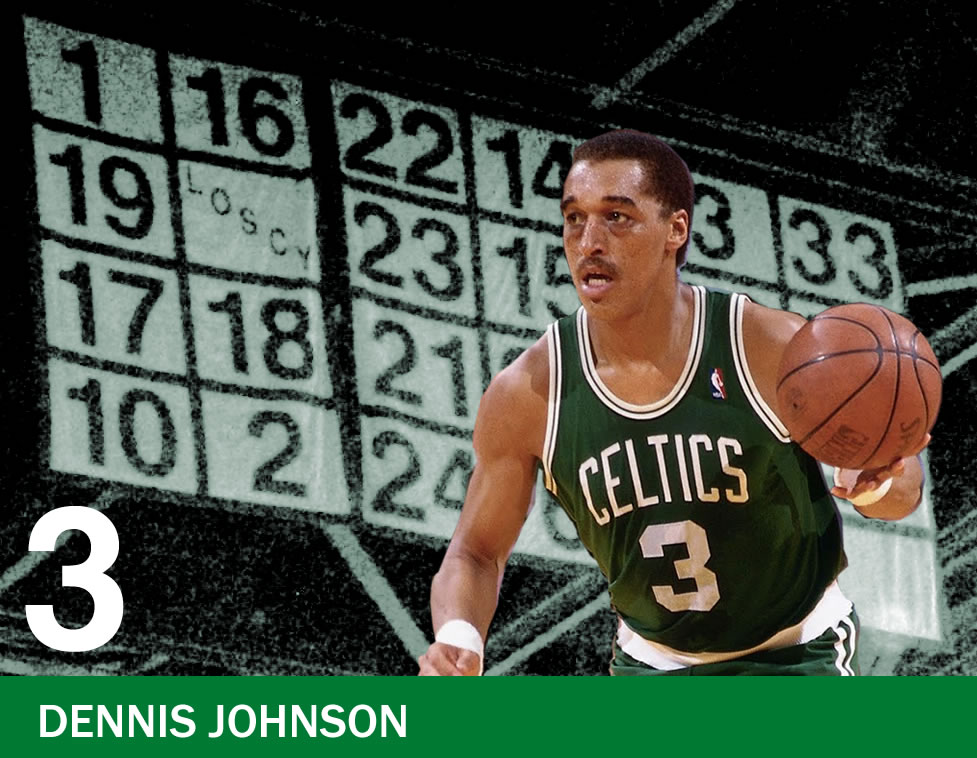

From now until February 11, Red’s Army will be posting stories about the players behind the Celtics’ 22 retired numbers and that one retired nickname. Stories will be posted in the order that the numbers were retired.

“He was the best teammate I ever had.” – Larry Bird

Dennis Johnson won a Finals MVP.

Even though Gus Williams easily led the Sonics in scoring in their five game ‘gentleman’s sweep’ of Washington in the summer of 1979, the best player on either end of the court, for either team, was Dennis Johnson. He averaged 21 points per game and dang near three blocks per game.

DJ was the link between Bill Russell and Larry Bird.

Bill Russell drafted DJ in 1976, in the second round, out of Pepperdine, which had pretty much the same reputation as a basketball powerhouse then that it does today. And since you’re scratching your head and saying, ‘what?’, well, exactly. DJ came out of nowhere. His rookie year, Russ played him over 20 minutes a game; he was a starter the following year and a Finals MVP the year after that.

For reasons that completely baffle me, no one seems to have asked Russ what he saw in DJ when he drafted him and coached him. Although, would anybody be surprised if Russ said it was his intensity?

The Celtics have had quite a run of incredible basketball players, but few of them played the game the with the fire that DJ, Russ and Bird had.

It took DJ a few years to get that fire under control. Nicknamed “Airplane Johnson” in his early years, Dennis followed up his Finals MVP season with a tumultuous season in which Hall of Fame coach Lenny Wilkins called him ‘a cancer on the team’ after he was traded.

The Sonics shipped DJ off to Phoenix for Paul Westphal and after three years of not exactly fitting into John Macleod’s system either, the Suns traded him to Boston for… Rick Robey (yet another one of Red’s absolute heists–seriously, why did people keep trading with him? Did each new victim think, “Ah! I’m finally the guy that got the best of Red in a deal!!”? I mean, forty years this went on!)

The Celtics had already won a title with Bird, McHale and Parish; but they had issues with big, fast guards. The Sixers’ Andrew Toney had already earned the nickname “The Boston Strangler” by the time the Celtics traded for DJ, having absolutely destroyed the Celtics in the 1982 playoffs.

Looming on the horizon was an even bigger, faster guard also named Johnson, out on the west coast.

The legends of those Celtics teams have already been written, and in those legends Dennis Johnson is a marginal player–even for many Celtics fans, especially those who aren’t old enough to have lived through the era.

He’s the other guy in, “There’s a steal by Bird, underneath to DJ” and, apart from that, well, ‘he was a good defender’ is about as far as the casual fan’s awareness extends.

But that’s not how it was at the time. Bird would get frustrated with McHale, Parish was a cipher, and Danny Ainge was a spoiled brat, but DJ? Bird respected DJ. Bird understood DJ and DJ understood Bird. They were simpatico.

Landing on a team with Larry Bird may have saved DJ’s career. He was finally on a team with someone else who approached the game itself with the same intensity. Yeah, especially toward the end of his career, he’d have games where it was pretty clear he was just marking time on the court, but they were never important games. If players were managed the way they are today, he probably would’ve been held out of most of those games with one nagging injury or another. But in that era, you played. When it mattered, DJ delivered. He had gone 0-14 in the closeout game of the 1978 Finals, and he spent the rest of his career burying that memory behind a string of clutch performances, starting with an MVP performance the following year.

DJ was tough. DJ was played-two-minutes-a-year-on-his-high-school-team-but-still-believed-he-could-make-it tough. DJ was take-a-$2.75-an-hour-warehouse-job-so-I-can-work-on-my-game-at-night tough. DJ was Compton rec-leagues tough. Refineries and oil fields tough. Eighth of sixteen kids tough.

In 1984, the Celtics beat the Lakers in no small part because of how well DJ defended Magic. When DJ retired, Magic called him the best back court defender he’d ever played against.

DJ was named to the NBA’s All-Defense team nine consecutive seasons out of the twelve he was a starter. He was also a five time All Star in his fourteen year career.

On offense, DJ wasn’t exactly a point guard, but he was usually the guy that brought the ball up when the Celtics were going into a half-court set. Nobody brought the ball up quite the way DJ did–he’d sort of saunter down the sideline, looking like he was walking a dog or going out to check the mail–maybe he’d be looking at the rest of the team, sometimes, I swear it looked like he was just staring off into space–and then after he’d sort of hypnotized the player opposite him, he would, out of nowhere, zip a pass right on the money to Bird in the front court.

He was not fast, but he was quick. He could release a pass and start the offense from that disinterested shuffle before defenders had time to get set and start guarding him. Certainly he had a knack for catching the rest of the defense napping.

On defense, he was, like Satch and Russell before him, a student of other players’ tendencies. He was another Celtic who took a particular satisfaction out of knowing what you wanted to do and preventing you from doing it. He was a physical defender too. If you played against DJ, you’d feel it afterwards. You were going to go through a workout.

In an era where the game was more physical, it might be easy to dismiss what DJ did as just a product of the times–that in some other era, he wouldn’t have been as good–but here’s the thing: Everybody got to guard their opposite with more physicality back then. Everybody. And DJ still stood out, not because he was allowed to play a more physical brand of basketball, but because he knew how to play basketball within the framework of the era. Stick him in any other era, and it would be the same: He would adapt because he was smart and he was driven.

DJ retired in 1990; the first from that era to hang up his shoes. He’d put in 14 seasons, and that was about all you could count on back then. You weren’t playing into your late 30s unless you were somebody like Jabbar or Parish.

The Celtics retired his number on December 13, 1991 when they hosted DJ’s first team, the Supersonics.

DJ got into coaching off and on after that, and in the mid 2000s, he caught on with the Austin Toros, which put him in line to work with Gregg Popovich.

It didn’t work out.

On February 22, 2007, DJ collapsed outside a hotel, dead of a heart attack at only 52.

He was not in the Hall of Fame when he died. That recognition came three years later, and at least fifteen years too late. Maybe the committee thought that there were already enough Celtics from that era in the Hall. Maybe they thought his defense was overrated. Maybe his occasionally brusque conduct toward the press poisoned the well. Maybe the committee thought they had plenty of time to recognize DJ while he was still alive.

But none of that worked out. DJ’s induction speech was given by his brother.

https://youtu.be/L4zd2LXNgwE

The retired numbers project:

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!