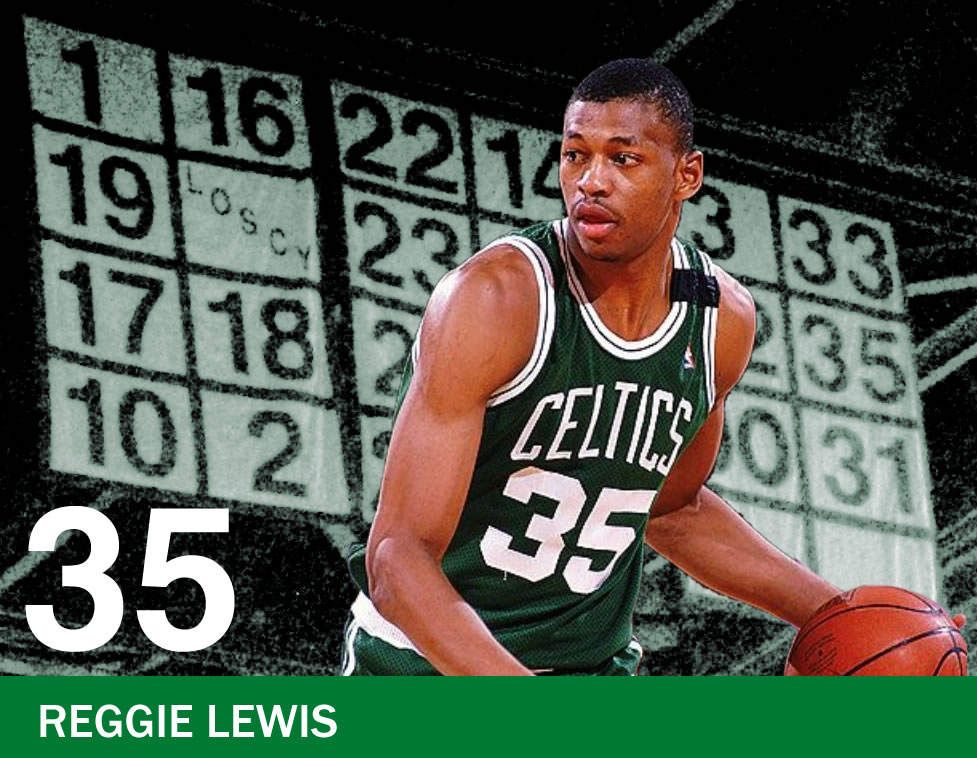

From now until February 11, Red’s Army will be posting stories about the players behind the Celtics’ 22 retired numbers and that one retired nickname. Stories will be posted in the order that the numbers were retired.

“I have one real regret–that I never had the pleasure and the honor to coach Reggie, because to me he personified everything a Celtic should be.” – Red Auerbach

First of all, we’re going to get something out of the way:

Reggie Lewis was on pace for a Hall of Fame career. He put up offensive stats comparable to Clyde Drexler, as the number three scoring option on a team with four future Hall of Famers. All you ‘BOSTON CITY OF CHAMPIONS!!!’ ‘We only honor winners’ types who think that Reggie’s number doesn’t really belong in the rafters, you can just step off right now–your ‘city of champions’ threw a party for Ray Bourque after the Avalanche won the Stanley Cup. Guys who wanted to give Reggie’s number to KD because Reggie wasn’t Bird or Russell, you want to nitpick Reggie’s career? Feel free to do so–if you’ve ever been half as good at anything as Reggie was at playing basketball.

Frankly, it’s embarrassing that this subject even needs to be dealt with, but well, here we are.

Yeah, I take criticism of Lewis personally. Reggie was my Celtic. I was three years old when Bird was a rookie; I remember bits and pieces of the ’84 and ’86 championships and the ’81 championship not at all.

My dad had followed John Havlicek’s career from start to finish, and that’s what I was going to do with Reggie.

In fact, that’s what I did with Reggie. I just never expected it to be over so soon.

Reggie was ten years older than me. That seemed like a lot in 1987, when he was drafted; it really doesn’t anymore.

The Celtics picked Reggie with their own (22nd) pick in the draft that year. Auerbach hadn’t pulled any of his trademark moves in order to draft Reggie. Nope–the Celtics got Reggie because Auerbach was still–36 years into it–smarter than pretty much everyone else in the league. Lewis was supposed to be a top ten pick, but he’d put in a poor showing at the combine in Chicago.

As Auerbach later told John Feinstein, “he was sick that week. He shouldn’t even have played, but he didn’t want the scouts to think he was chickening out, so he went and played anyway.”

“These guys go to games all season, they go watch these guys practice, they talk to their coaches. Then they watch them play for two days in Chicago or for one day in a workout and they change their minds about them. If a guy is good in games, he’s a good player. If he works hard in practice, that means he’s going to work hard in practice.”

So Reggie, another alum of Dunbar High in Baltimore, and a graduate of Northeastern in Boston, became a Celtic.

Lewis didn’t play much his rookie year, but when Bird missed most of the 88/89 season, Reggie was in line for a lot of minutes, and he delivered.

What was Reggie like? Man, he was smooth. He made the game look easy. He made it look like a game. He was out there playing, while other guys worked.

There are guys in this league that make your jaw drop. Reggie wasn’t one of them. Reggie was one of those guys who made it all look so easy, you’d fool yourself into thinking basketball wasn’t that hard, and then when you tried to move the way he moved or shoot the way he shot, you’d realize just how good he was.

Reggie was a player’s player.

It would’ve been real easy for a guy picked 22nd and stuck on a team with Bird, McHale, Parish and Johnson to be overwhelmed, but Reggie wasn’t. He wasn’t cocky. He didn’t trash talk like Larry, he didn’t have a fiery on court demeanor, but he knew he belonged out there with those guys. He had that confidence.

Michael Jordan compares him to Joe Dumars, “Joe never talked trash, and Reggie was the same way. If you started yapping at either of those guys, they just smiled at you.”

“‘You can say what you want, but I’m still going to play my game.'”

Reggie had gotten involved in community activities while he was an undergrad at Northeastern. A tradition of giving away turkeys that he started in college continued on into the pros–without the Celtics’ knowledge at first.

I suppose, if you tried, you could find someone, somewhere, with something bad to say about Reggie, but you’d have to look awfully hard. Even while he was still playing for the Celtics, he had a reputation as an open-handed and generous guy off the court. Kids would share stories about how he’d just show up at a neighborhood playground and get up a few shots and sign a few autographs.

Lewis married his girlfriend from college, Donna Harris, in 1991. They had two kids. The oldest, Reggie junior, was born in 1992. Donna found out she was pregnant with their daughter, Reggieana, on July 27, 1993.

The Boston Celtics’ season ended in the first round of the playoffs in 1993. It was the team’s first year without Bird, and Reggie Lewis had been named the Celtics’ new captain.

In the first game of the first round of the playoffs, back when the first round was a five game affair, Reggie collapsed while running up the court in the second quarter.

He’d scored 17 points in 13 minutes of play.

Initially, team doctors had no idea what had happened. Reggie’s only obvious symptoms were dizziness and shortness of breath.

The eventual diagnosis was that Reggie had a heart defect, and that his basketball career was over.

Reggie sought a second opinion, and the doctor he hired, one Gilbert Mudge, said that he was only prone to ‘benign fainting spells’, and that he had a ‘normal athlete’s heart.’

With that, Reggie put together plans to make a comeback with the Celtics. On July 27, 1993, he popped into the gym at Brandeis University, checked in, grabbed a basketball and started doing a bit of practice shooting. He collapsed again, and was pronounced dead two hours later.

A few people since then have criticized Reggie (and his wife Donna) for trusting that second opinion, but let’s be honest here. Reggie wasn’t going through intensive training when he collapsed that second time. He was just shooting baskets. With a heart that weak, he was at high risk no matter what he did.

Unfortunately, there were people, Gilbert Mudge among them, who simply couldn’t let Reggie rest in peace.

Only seven years and change after Len Bias had died of an overdose, cocaine was still a specter in professional sports–especially basketball, and especially among players of a certain hue. Bearing no obvious similarity to Len Bias other than his general complexion, Lewis was asked how he planned on celebrating after he was drafted, “I know a lot of people have Len Bias on their minds. I know people want to make sure the same thing won’t happen to me.”

It didn’t help that Reggie’s mother was a lapsed cocaine addict.

As early as November 1993, the Boston Globe had published an article that questioned the way the Celtics medical staff had handled Lewis, but the real trouble started in March, 1995, when a Ron Suskind story in the Wall Street Journal didn’t openly accuse Lewis of being a cocaine user, but did everything short of that.

The star witness for Suskind? Gilbert Mudge. Mudge told Suskind that “cocaine is the only thing that would explain what we’re seeing”.

Mudge–the guy who had confidently assured Reggie that he had no heart problems whatsoever, was equally confident in assuring Ron Suskind and the Wall Street Journal that cocaine was the only conceivable explanation for Lewis’s death. Whole swathes of Suskind’s story relied on statements from Mudge that could not be corroborated by anyone. Not only did Mudge thoroughly botch Reggie’s initial diagnosis, here he was two years later helping Ron Suskind all but accuse Lewis of killing himself with cocaine.

The toxicology report at the time Lewis died came back pristine.

No one has ever said, on the record, or even anonymously, that they saw Reggie use cocaine.

And yet, Suskind’s story combined just enough innuendo, just enough selective presentation of facts, just enough allusions to the problems that other people of color in professional sport had, to get traction.

Suskind’s article was published not even two weeks before the Celtics’ number retirement ceremony for Lewis, and it cast a pall over that event.

Even today, Suskind’s just-this-side-of-libel article has become an inescapable piece of Reggie’s legacy. I can’t stand that article–and I could point out a dozen or more areas where Suskind manipulates his readers–and yet I have to discuss it in an article about Reggie Lewis because that thinly reasoned bit of sensationalism stuck.

Why? Why did this story stick?

Because Reggie Lewis was black.

If you’re in your 20s or early 30s, and all you know about black people and cocaine is what you’ve laughed at on the Dave Chappelle Show, you have no idea.

You have no idea.

In the 80s and 90s, people were ready to believe that any black person, no matter what he or she had accomplished, was on crack–or if they could afford it, cocaine. Your skin color was 90% of the evidence required to convict you of using–and if you were from an inner city environment, well, shoot, that was worth another 9% right there.

In some other alternate timeline, this would’ve been a celebration of Reggie’s long career and Hall-of-Fame standing, but that’s not what we have to deal with. What we have to deal with is a world class basketball player, a guy with an unimpeachable reputation off the court, whose tragic death was followed by an attack on his character and the gradual erosion of respect for what he did as a player.

But no matter how his career ended, Reggie was my Celtic; heck, in some ways he still is my Celtic.

https://youtu.be/ajhGVHj3Ycg

The retired numbers project:

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!