No other professional sport on planet earth is more defined and illuminated by statistics than Major League Baseball. As the professional game celebrates its 150th anniversary this year it’s important to note that there is also a rich history of baseball statistics.

That timeline runs from the early 19th century baseball to the first professional team, the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings, right up to the game’s 21st century information-driven franchises.

That timeline runs from the early 19th century baseball to the first professional team, the 1869 Cincinnati Red Stockings, right up to the game’s 21st century information-driven franchises.

There are a number of brilliant and impactful people in the game’s history who have looked at MLB stats in revolutionary ways. The result of their work has forever altered our understanding, and increased our enjoyment, of professional baseball.

Whether they worked for teams, wrote for newspapers, or authored paradigm-changing books, the following five stat-cats define the evolution of MLB statistics:

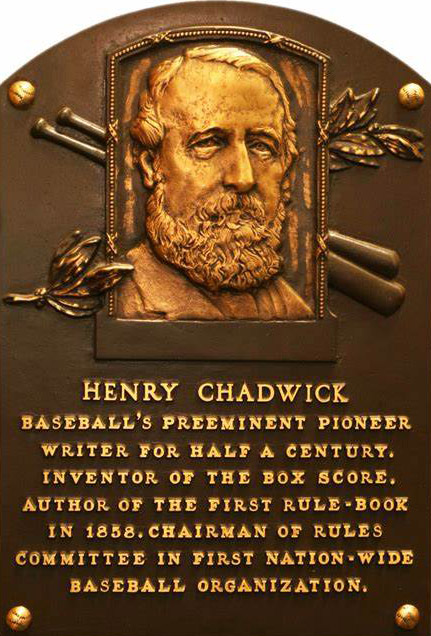

Henry “Box Score” Chadwick

All discussion of baseball stats begins with a respectful bow to the British-born sports writer Henry Chadwick (1824-1908).

While covering cricket for the New York Times in 1856, Chadwick happened to see his first baseball game– a contest between the New York Eagles and the Gothams at Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey.

He also created earned run average and batting average to better measure individual player performance.

But my favorite Chadwick creation was the abbreviation “K” to denote a strikeout. The use of the letter “K” for a strikeout is obviously intuitive, but for some reason has routinely baffled casual fans over three different centuries.

Sadly, there is little information about who exactly created the “reverse K” to note that the batter was out on a called third strike. Popular history traces it to Mets fans in the 1980s, who began posting “K” signs at Shea Stadium when Dwight Gooden was pitching, and began reversing the “K” on called strikeouts.

Ernie Lanigan Orders Up Some Rib-Eyes

The RBI emerged in 1879 when a local newspaper tabulated RBIs for the National League’s Buffalo Bisons. The Chicago Tribune did the same in 1880 for the White Stockings, but it didn’t stick because some fans felt that leadoff hitters were disadvantaged in accumulating RBIs.

The RBI stat was officially adopted by Major League Baseball in 1920, primarily because it had been championed for years by sportswriter/editor/historian Ernie Lanigan (1873-1962).

The “RBI” rule was initially enacted in 1920 but was so poorly defined that Major League Baseball had to revisit the rule in 1931 and more precisely classify how hitters were awarded an RBI.

Despite the problems with the intrinsic value of RBI there is a current movement among sabermetric writers and researchers to have pre-1920 RBI added to historic player career statistics.

Babe Ruth, for example is credited with 1,990 RBI from 1920 through the end of his career in 1935. But research has shown that Ruth knocked in 224 runs from the start of his career in 1914 through 1919.

So Ruth’s actual career RBI total should be 2,214. Why this oversight isn’t being officially corrected by Major League Baseball is ridiculous on a grand level. Can we get us some replay on this issue…?

Side note #1: I should note at this point that it is now generally accepted that RBIs are a distracting and inaccurate measure of individual player performance.

For a hitter to get an RBI, other players not only need to be on base, they must also be in scoring position. Plus the range or lack of range of defensive players and whether they have a “good arm” or a “bad arm” often determines whether or not a batter gets an RBI.

Back to Ernie Lanigan. Lanigan was first to track “caught stealing” stats which were also officially recognized by Major League Baseball in 1920. The American League began tabulating the stat for every game, but for some reason caught stealing was not adopted as an official stat by the National League until 1951.

Side note #2: The first player in MLB history to be caught stealing four times in one game was 2B Robby Thompson of the San Francisco Giants in a game against the Cincinnati Reds on June 27, 1986.

The Reds’ catcher that day was Bo Diaz and the Giants won that 12-inning contest 7-6. Catching the entire 12 innings for San Francisco was Bob Melvin (now manager of the Oakland As). The Reds lineup featured Pete Rose, Dave Parker, Dave Concepcion, and Tony Perez.

F.C. Lane Spreads the Word, and the Word is Good

Ferdinand Cole Lane (1896-1984) was the brilliant and highly opinionated writer/editor of Baseball Magazine from 1912-1937.

In particular, Lane condemned the batting average as “worse than worthless”. The idea of counting doubles, triples, and home runs as the same as a single made no sense to him and he crusaded for decades against its use.

He also devised several versions of “runs created” by putting a value on each base reached, and worked on a run probability predictor based on the number of outs and men on base.

F.C. Lane pioneered examining stadium effects on hitting and pitching, listing which pitchers had the best control, and which hitters were the easiest to strike out.

After his career in baseball journalism Lane created a whole new life as a college history professor and extensive world traveler.

In thinking about F.C. Lane, there’s little doubt he would have felt completely at home holding court at the annual SABR Analytics Conference.

Allan Roth: Asking Questions and Getting Answers

Perhaps the most impactful influence on our understanding of inside baseball came from statistician Allan Roth (1917-1992), who worked for the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers from 1947-1964.

Roth was hired by baseball’s preeminent executive intellect, Brooklyn Dodgers President and GM Branch Rickey (1881-1965), after Roth repeatedly pestered Rickey with new statistical concepts he said would allow the Dodgers to win more baseball games.

Rickey eventually hired Roth in 1947 at a salary of $5,000 a year, and he became the first full-time statistician ever employed by a Major League club. For the next 17 years every pitch thrown by a Dodgers pitcher was recorded and tracked and detailed hitter spray charts were created.

Roth and Rickey quickly bonded over their mutual agreement that on-base percentage was the game’s most critically overlooked statistic and that RBIs were a false indicator of hitting talent. They also shared a passion for questioning traditionally accepted assumptions about how Major League Baseball should be played and managed.

Allan Roth famously created “The Equation”, a legendary combination of on-base percentage and isolated power, plus run-scoring, pitching and fielding, that measured player performance more precisely than any existing stat.

Other Roth innovations include making situational pitcher and hitter scenarios (righty vs lefty, day game vs night game, home/away games, stadium effects, etc.) part of the game’s on-field strategy for the first time in MLB history.

Roth also formalized the concept of a pitching “save”. He began tracking saves in 1951 and did so until Chicago Sun-Times sportswriter Jerome Holtzman revamped Roth’s “save” definition in 1960 and pushed to have his version made an official MLB stat. The save was adopted by baseball in 1969.

Bill James: Asking Questions and Extracting Astounding Answers

Bill James took the concept of examining traditional assumptions and asking pointed questions about quantifiable performance to a higher, more intellectually rigorous level.

Major League Baseball has traditionally been a closed, backward-looking institution more fiercely dedicated to defending long-held beliefs rather than examining them.

The historic examples of F.C. Lane and Allan Roth were quickly and happily forgotten as the baseball establishment closed ranks and continued to value untested doctrine over exploring potential alternatives to achieve greater on-field success.

But James also recognized the work of fellow analytical investigators, which for the first time in the game’s history morphed into a sustained and influential analytics community.

What followed was an exponential expansion of knowledge and a tectonic reset of virtually every aspect of basic Major League baseball. As of 2019, there are dozens of new research and experimental directions being explored.

Progressive MLB teams like the Houston Astros, Los Angeles Dodgers, New York Yankees, Chicago Cubs and Minnesota Twins are creating proprietary management models to expertly inform their amateur drafting, player development, and player psychological deconstruction.

What will happen over the next ten years should be breathtaking.

But maybe the real difference maker today is that players have begun to stop relying on whichever MLB team they happen to belong to provide the process to improve their athletic performance.

Today’s ballplayers are better informed and have begun to take control of their own individual development by partnering with cutting edge private sector science.

Which means that the future of Major League Baseball, union and contract issues, and advances in player development are about to plunge headfirst into the next uncharted dimension.

[Sources: “The Numbers Game” by Alan Schwartz (Thomas Dunn Books); Society for American Baseball Research (SABR); Baseball-Reference.com]Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!