The recent news that team spending on Major League Baseball payrolls decreased by $18 million in 2018 compared to 2017 could not have been a champagne-popping moment for the MLB Players Association.

Part of the reason for last season’s salary decrease was the suspensions of several players without pay for drug or domestic violence incidents, and the rare occurrence of a player retiring in midseason (OF Colby Rasmus gave up $1.5 million rather than try to rehab a hip injury).

Part of the reason for last season’s salary decrease was the suspensions of several players without pay for drug or domestic violence incidents, and the rare occurrence of a player retiring in midseason (OF Colby Rasmus gave up $1.5 million rather than try to rehab a hip injury).

But I’m guessing that players union head Tony Clark isn’t happy that all it took was $18.8 million in suspended pay and one early retirement to create the first yearly payroll drop for his membership since 2010.

And MLBPA’s current player salary problems don’t remotely end there.

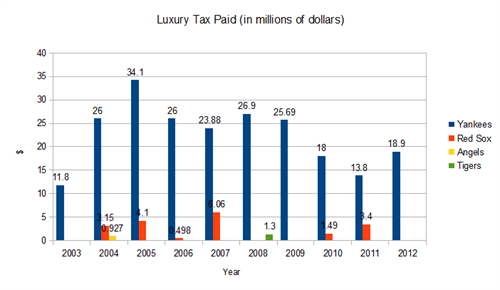

In 2017 for instance, the Yankees and Dodgers paid a combined $52 million on top of their payrolls for surpassing CBT limits.

But even teams increasingly using the luxury tax as an excuse to stop runaway payrolls isn’t the worst news for the players’ union.

Right now we are in the second consecutive off-season of a spending freeze in Major League Baseball that threatens to further upset the fiscal balance between owners and players.

As we slowly crawl through the 2018-19 Major League Baseball off-season we’re seeing the continuance of last year’s game-changing tilt toward more MLB team wealth and fewer free-wheeling free agent player signings.

While star players and their agents are still looking for the record-breaking contracts historically associated with free agency, baseball’s fiscal terrain has dramatically and permanently changed.

For two reasons.

First, the surge of predictive advanced analytics has finally gotten through to baseball owners and their Ops people.

Teams are no longer eagerly w

Second, we’ve known for over a decade that the traditional timeline of a player’s “prime” was historically misunderstood. It’s just taken a long time for the MLB establishment to acknowledge that and begin to make money decisions based on actual player-aging data.

Rather than the 28-32 age spread that was traditionally accepted as a player’s “prime” (without any real documentation), there has been a flood of detailed research over the past twenty years (Baseball-Reference.com, Baseball Prospectus, Bill James, etc.) demonstrating that a player’s actual “prime performance” years are the ages of 26-28.

And for pitchers it appears that prime performance years start even earlier, at the age of 24.

Obviously, exceptions can be cited. This is not a rule that applies to every MLB player—just to the overwhelming majority of all MLB players, using decades of measured and weighted performance.

But the result of these trends has allowed MLB owners and front office executives to be increasingly successful in controlling and directing player markets.

Here are several of the rules now being enforced in the marketplace by virtually every Major League Baseball franchise:

- Say goodbye to big multi-year contracts for players 30 years old and older. Production-wise these fiscal albatrosses rarely work in a team’s favor, and sooner or later they’re guaranteed to crush team payroll flexibility.

- The stock of big-bopper corner infielders and outfielders has taken a huge hit as teams shift to valuing more impactful strategies: solid bullpen construction, building depth in their 25-man rosters, and demanding that up-the-middle fielders be run producers as well as premier defenders.

- Control of the direction of baseball’s future is no longer in the hands of star players and renegade, dynasty-building owners.

Which includes more complex player development techniques; increased delivery of live-game information to players and managers; and dramatic advances in physical and mental conditioning.

Not only are all of these new wave rules increasing efficiency, they’re also proving to be much more cost-effective.

Players, Fans and Competitiveness

Baseball fans will not like hearing this, but MLB players on rival teams don’t “hate” each other. They don’t generally root against players on other teams, and they rarely get into on-field arguments or actual fights with rival players.

Baseball’s classic team “rivalries” may have been real decades ago, but now they’re just another promotional marketing gimmick to engage fans.

Every ballplayer on the St. Louis Cardinals and Chicago Cubs, on the New York Yankees and Boston Red Sox, and on the Los Angeles Dodgers and San Francisco Giants has two very compelling things in common:

They are all members of the same labor union, and virtually all of them are millionaires.

It’s illustrative to put player salaries into an everyday context.

In 2018, the average MLB player salary was $4,095,689. Here’s how that looks in the real world:

- If you get paid every two weeks, that’s $157,526 each paycheck all year.

- If you get paid once a month, that’s a $341,307 paycheck on the first of each month.

- While no one gets a daily paycheck, if you did it would be $11,221 each and every day of the year.

The 2019 league minimum salary, paid to players called up from the minor leagues, is $555,000. That’s a bi-weekly paycheck of $21,346. All year.

All of which, by the way, Major League ballplayers absolutely earn and richly deserve.

The average fan isn’t aware of what it takes to succeed at the Major League level: the all-consuming commitment to physical training, understanding the game’s expanding knowledge base, playing with injuries, and having the competitive fire to continually excel.

Making it to the Major Leagues is an extraordinary accomplishment, having an extended career in the Majors is an astounding accomplishment. On any given day (until the rosters expand in September), only 750 athletes qualify for the job of “Major League Baseball player”.

But in an industry with revenues that soared past $10 billion last season, the issue of franchise wealth versus player compensation has become deadly serious business.

Because right now the balance between ownership revenue and player compensation is out of whack—the players’ union is struggling to get their fair share of the pie.

For some strange reason, baseball fans are shocked each year when top MLB player contracts increase– from $25 million a year to $30m, to $35m, and so on.

Sometime in the next month, when free agent outfielder Bryce Harper signs a $360 million, ten-year contract, fans will be aghast all over again.

But guess what? In the next 5 years or so we will see $50 million a year player contracts, and the increases won’t stop there.

How can that be? Because the value of every MLB franchise increases each year; and because MLB’s lucrative national and local media contracts provide each team with a tsunami of hard cash revenue.

With a new Collective Bargaining Agreement between ownership and the players due to be in place before the start of the 2021 season, the players’ union faces a huge challenge:

MLB team revenue is increasing at a much higher rate each season than cumulative player salaries.

So… Exactly How Much Money are Baseball Owners Making?

It’s difficult to fully understand the immense swath of Major League Baseball revenue streams.

A great deal of fiscal informa

Multiple credible sources (Forbes, USA Today) say MLB passed the $10 billion mark for the first time in 2017 and hit $10.3 billion in 2018 (an average of $343 million per team).

The Baseball Commissioner’s office has said that 2017 saw overall revenues hit $9.1 billion, and $9.4 billion in 2018. With 54.2% of that amount going to Major and Minor League player salaries.

All of which demonstrates that it’s challenging to get to the bottom of MLB finances. But for our purposes let’s look at what we know about how MLB revenue sources have shifted in the past twenty years:

> This will seem counterintuitive to the average baseball fan, but stadium attendance is now one of the least significant revenue streams for all 30 MLB clubs.

Sure, every owner and ownership group would like to see their stadiums filled on game days. Mostly because it looks good on TV.

But in terms of cash value, selling tickets, hot dogs, and replica jerseys may bring in several hundred million dollars a season, but much of that is offset.

Stadium construction or lease costs, utilities, insurance, ongoing maintenance, public relations and ticketing operations are significant. There are also personnel costs for ticket-takers, ushers, food servers, clean-up crews, security, and grounds-keeping employees.

Baseball stadiums cost a lot to run. Luckily, team owners also constantly receive enormous amounts of “free” revenue. Simply because they’re owners.

> Media contracts, revenue sharing, developmental technology, and stadium naming rights.

This is where every MLB franchise prints money non-stop, no matter how their team performs, no matter how many fans buy tickets, no matter which players they sign every season.

Every MLB owner makes tens of millions of dollars each year by simply unlocking the main gate to their stadium every Opening Day. Figuratively waiting for them in the team mail box is a bundle of multi-million-dollar checks.

- National TV media.

In November 2018, Major League Baseball signed a seven-year deal with Fox Sports for $5.1 billion to broadcast MLB weekend and playoff games.

While it’s reasonable to assume the Commissioner’s Office takes a percentage cut of all MLB media deals, absent that information, it means each MLB team’s cut of the Fox deal would be about $25 million a year.

> MLB additionally has a national media contract with Turner Sports for $2.65 billion from 2012-2021. That 10-year deal brings in another $8.8 million a year for each MLB franchise.

> MLB also has a current 10-year deal with ESPN to broadcast a weekly game and playoff games for $5.6 billion. Which is another $18.5 million a year for each team.

> Last season, MLB cut a deal with Facebook to exclusively broadcast 25 afternoon games for $30 million. Another million dollars for every team.

- Local TV media (from FanGraphs/2016).

Every Major League team has exclusive local television and radio contracts. We won’t list all of them here, but here’s a sample of that revenue:

> The NY Yankees have a $5.7 billion 30-year (2013-2032) cable TV deal; an average of $190 million a year.

> The Seattle Mariners have a $1.8 billion, 18-year (2014-2031) cable TV deal; an average of $76 million a year.

> The San Francisco Giants have a $1.75 billion cable TV deal over 25 years (2008-2032); an average of $70 million a year. Plus the Giants own 30% of the local media outlet.

- Each team also has separate local radio contracts, and a share of national radio broadcast rights.

- Stadium naming rights. Virtually every MLB team sells its stadium naming rights.

The San Francisco Giants just cut a deal with Oracle technology to rename AT&T Park “Oracle Park” for the next twenty years.

It’s estimated that the deal is for about $325 million, an average of over $16 million a year in revenue for the Giants.

- Proprietary MLB technology.

This is an emerging and complex revenue source for Major League Baseball. In 2016 the Disney Company announced that it was buying a 33% share in MLB Advanced Media (BAMTech) for $1 billion.

BAMTech, funded by MLB, is a global leader in direct-to-consumer streaming services, data analytics and commerce management with 8 million subscribers. The deal brought an average of $33 million to each MLB franchise, plus ongoing revenue because MLB still owns 67% of BAMTech.

This much is clear. The complexities of MLB revenue is a labyrinth of media and proprietary resources. And stadium attendance, which used to be the gold standard of success, is increasingly a fiscal footnote in the game’s current avalanche of cash.

The bottom line going forward is this: how can the players’ union, representing the people who play the game and create the revenue, get their fair share of the riches.

Right now Major League Baseball’s fiscal hammer is in firmly the hands of team owners and their representative, the Commissioner of Baseball.

How the Commissioner and the owners handle the upcoming negotiations for the new Collective Bargaining Agreement will greatly determine the game’s future.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!