I could hardly contain my anticipation at school as I tried to make it through my daily schedule. It was September 18th, 1987. I never before realized how many kids had skeletons, dancing bears, or drawings of Jerry Garcia on their binders and backpacks before that day. It was no surprise that there were a lot less kids in the smoking section than usual that Friday.

I don’t think any of the Deadheads at Horace Greeley High School suspected that I would be joining them that night, let alone end up attending more Dead shows than they ever did. But once I got into something, I didn’t know how to do it halfway. With my short brown hair and khaki pants, I looked more like a T.G.I. Friday’s employee than a guy about to see his first Grateful Dead concert. I considered the rule about not wearing the shirt of the band you were going to see, but wasn’t making a conscious effort to not be a poser worse than actually being one? I didn’t own a tour shirt, anyway. My magenta tie-dye commemorating Ben and Jerry’s brand new “Cherry Garcia” ice cream flavor would have to do.

After spending the day squirming at my desk, I was more than ready to get the fuck out of dodge. As soon as school ended, I drove my parents’ silver Volvo GL to the Chappaqua train station. Fortunately, there was a deli across from the platform that didn’t proof you for beer, so I got a six-pack of Bud for me and Rose. Stoney, who had the tickets, was meeting us at the Garden. As I waited for the train, I wondered if it would be okay to drink on the train. As soon the doors to the car opened, however, I knew there was nothing to worry about.

I would soon recognize this as the “scene” that accompanied all Grateful Dead concerts. However, it would usually be spread out over numerous parking lots, rather than a single train car. There were people smoking joints, passing around liquor bottles, and blasting tapes. I was even able to identify a few bootlegs from my growing collection. After finding a seat, I took a long gulp of my beer and waited for the train to hit Scarsdale. When it finally did, however, Rose wasn’t standing in the doorway. That was okay. He must just have gotten on via another car. I wondered if they were all as wild as this one, but as soon as I saw him walking down the aisle with his mouth agape I knew the answer.

“Wow,” he said. “It’s a circus already.”

I handed him a beer in agreement. We each polished off two more in the thirty minutes it took to get to Grand Central. As the car emptied out, we decided to walk to the Garden to temper our buzz a bit. As we reached the top of the staircase, a kid with dirty blond hair and a hooded poncho sidled up next to me. I must have given off the scent of the uninitiated since he immediately asked me if this was my first show.

“Yeah, it is.”

“You’re so lucky, dude. Get ready for a greeeeaaaat time.”

“Cool shirt, dude. I haven’t seen that one on tour.”

The scene outside the Garden was similar to what I saw on the train, except it had now spilled onto the streets of Manhattan. The police were everywhere, but seemed to be observing rather than trying to control the action. It was at this point that I realized that there wasn’t even a conductor to take tickets on the train. All the authority figures were hanging back tonight.

That appeared to be the only way to handle the circus on 7th Avenue. There were people selling handmade T-shirts, asking for extra tickets, and handing out flyers with the setlists from recent shows. I even saw someone selling a stack of grilled cheese sandwiches. I had no idea where or when they cooked them and didn’t want to find out. In the middle of all this stood Stoney with a huge smile underneath his mop of light brown hair.

“How awesome is this?”

We didn’t even need to answer as he handed us our tickets. We were in the upper deck of the Garden, but we didn’t care. We were so fired up after going through the turnstiles that none of us partook as joints were passed our way. After finishing our climb to our seats, I looked at my watch. It was 8:00 PM, thirty minutes after the scheduled start. Everyone said that the Dead never began on time, anyway. This was just another way the band defied convention, which held obvious appeal.

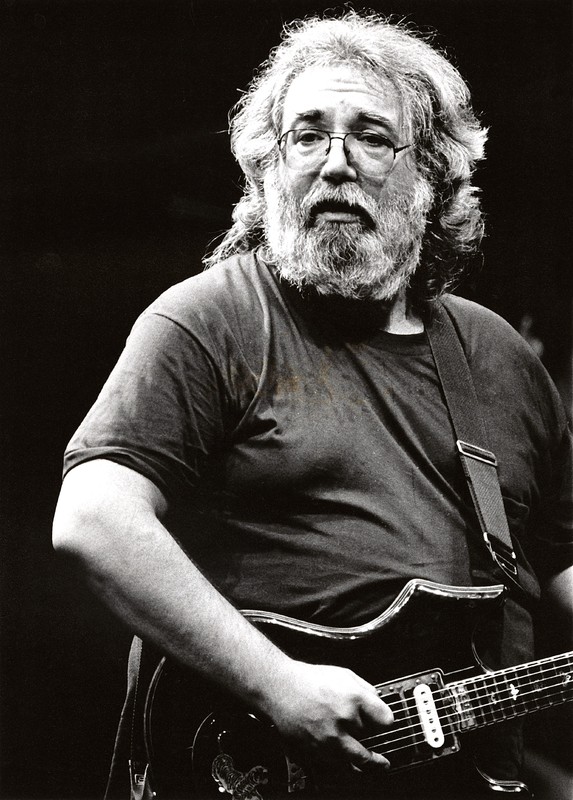

As we waited for the lights to go down, I looked at the gear already on the stage. There was a giant rug which looked like it belonged in my grandparents’ condominium. Speakers were stacked on both sides, but there were no other identifiers as to which band was playing that night. The air of anticipation inside the building made it perfectly clear that everybody knew who would be taking the stage. At about 8:30, the Garden finally went dark and a huge roar erupted. The band walked out and took what I would come to learn were their usual spots. Under us on stage left was Phil Lesh, who looked like a high school shop teacher. His glasses seemed to support his Lego-like helmet of brown hair and his rainbow tie-dye was the only evidence that he was in a band. The guy next to us assured us that, even this high up, “Phil’s side always has the best sound.” Bob Weir, the youngest band member and the closest thing the Dead had to a rock star, occupied the middle microphone. He was wearing black Converse hi-tops, a black T-shirt ripped around the collar, and cut-off jean shorts. This was an odd look even in 1987. Jerry Garcia occupied the last slot and wore his usual black T-shirt and corduroy pants.

I knew that the band didn’t say very much to the audience. They let the music do the talking. The video footage I had seen of them suggested that they were really working on the fly. The looks the band gave each other also hinted that there were many times that they couldn’t get it going at all. Luckily for us, this wasn’t one of those nights.

They didn’t introduce a single song, but the crowd recognized each one within a few notes. When they played, they looked like they were all soloing at once. Jerry’s guitar was undoubtedly the catalyst, but he never acted like a rock star playing to a sold-out crowd. When one of his solos caused the crowd to explode, his only response was to push his glasses back up the bridge of his nose. This seemed like another outlaw move to me. After all, this was the band who once tried to get Warner Brothers to let them call one of their albums Skull Fuck. (It was the one with the skeleton and roses on the cover.)

When the lights came on to signal the end of the first set, the first thing we saw was the guy at the end of our row snorting a line of coke off the armrest of his chair. Before we could even react, he sprung up to give us his assessment thus far:

“Hot set, but short. They’re really gonna tear shit up from here on in.”

He was right. When they reemerged from backstage, you could already tell that the second set was going to be where they really delivered. We all sat in the smoky darkness in anticipation as they tuned up. Jerry’s fingers ran up and down his fretboard and the crowd immediately recognized “Shakedown Street.” As a roar came up from the audience, both drummers erupted in what sounded like firecrackers.

WOOWWWWWWWWWWWWHHHHHHH!

But it was the version of “Morning Dew” they played about an hour later that really made the night legendary. Jerry may have looked like Santa Claus by 1987, but he sang this ballad with all the emotion of a screaming child. You could tell by the looks of the other band members and the shrieking crowd that he didn’t get this raw very often. His solo was even better, as he poured even more emotion into the notes than the words. There were times that it even sounded like the guitar cracked like a creaky voice from being played so fast. This isn’t just hyperbole. This version of “Dew” is universally considered one of the best ever. The whole show was later released in the career-spanning box set that featured one concert from each of the band’s 30 years.

By the time it was all over, we three knew we’d be back. I looked at Rose and Stoney and knew none of us were thinking about our respective train rides home. We went to more shows together, but they eventually tapered off. I, of course, couldn’t exercise such moderation.

I’m glad I didn’t. I saw other shows that were so good that they became live albums and others that were average or downright disastrous. That only made the special ones better because I saw what it took to get there. I went to as many concerts as I could to maximize the chances of seeing “the one.” When the band was in front of me, I knew that for one night I wouldn’t have to wonder what or how they played.

However, it became about more than just the music. Dead shows gave me a sanctuary when it seemed like the real world was closing in too fast. I didn’t need to worry about responsibility on tour. I could just be. Years later, the shows themselves became the responsibility. By that time, I was no longer taking vacations, but hiding from reality. On that Friday however, I still had 137 shows to go. I boarded the train to Chappaqua only thinking about the next one and how I was going to track down a tape of what I’d just experienced.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!