The MLB Labor Wars Part 2: Prelude to Labor-Armageddon

1990 Season – Baseball Owners Swing and Miss from their Luxury Boxes

On February 15, 1990 Major League Baseball owners enacted a 32-day Spring Training player lockout, still fighting player free agency and arbitration issues. They also wanted to implement a player payroll salary cap for all teams.

Or in this case, both feet.

Once again the players’ union came out ahead, avoiding a baseball-wide salary cap and increasing the minimum salary for players from $68,000 a year to $100,000 a year.

Because of the lockout and the CBA impasse, the season started several days late but the full 162-game schedule was played.

1994-95 Seasons – Here’s an Idea: Let’s Threaten the Entire Future of the Game

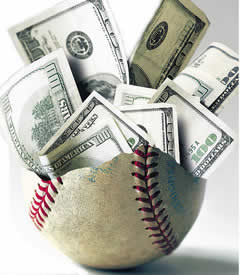

The most damaging labor strike in professional sports history cost MLB owners and players tens of millions of dollars and managed to alienate one of professional sports’ most devoted fanbases for years after.

And it’s particularly striking how ugly things got in this final labor battle, specifically the moment baseball owners decided to hire replacement players to take the jobs of striking MLB players.

Over the past twenty years the MLBPA had increasingly won significant concessions, attained greater control of the game’s structure and direction, and had institutionalized players’ labor rights. And all that had to stop.

This was a generation of empowered and privileged owners who were not used to being forced to share increasingly larger pieces of the sport’s revenue pie with the help. So MLB’s owners decided to take on the players’ union one more time.

What the owners wanted was to solve the great disparity between big market teams like the Yankees and Chicago and small market, low revenue teams like Pittsburgh and Milwaukee. Increasingly, the ability of small market teams to compete was marginalized, which would eventually affect big media contracts and the overall economic health of the game.

MLB’s solution was to create a salary cap for all teams, which would limit big money franchises from going on free agent buying sprees and simply spending their way to the post season.

They also wanted a salary floor which they felt would make small market franchises more competitive; additionally, these teams would be helped by receiving revenue sharing from the high-end franchises.

Of course the players’ union was adamantly against limiting player salaries in any way– whether it was through free agency, arbitration, or a game-wide salary cap. The MLBPA was not in the business of solving the owners’ big-market/small-market problems.

The union was aware that the owners could declare an “impasse” and simply implement their original seven-year proposal at any time. So on July 28th the MLBPA declared all players would go on strike on August 12, 1994. Which they did.

Four years before, Fehr had wisely anticipated the need for a players’ strike fund, so when the new strike began the union had over $175 million reserved to provide paychecks to the players during any labor actions. Players with four years or more service would receive about $175,000 a year.

This would be the first time since 1904 there wouldn’t be a World Series played. (In 1904 the NY Giants won the NL Championship and the Boston Americans won the AL Championship. Animosity between AL President Ban Johnson and Giants Manager John McGraw culminated in McGraw refusing to play a team from the “junior league” in a World Series.)

The estimated cost of ending the season in mid-September was almost $600 million for the owners and some $230 million in player salaries.

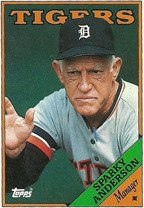

In December 1995 the owners finally did unilaterally implement their original salary cap. In response players’ Executive Director Donald Fehr declared on January 5, 1996 that all 896 unsigned MLB players were now free agents.

Then on January 13th the owner’s executive council approved the hiring of replacement players to start the 1995 season. Each replacement player would receive a $5,000 bonus for reporting to Spring Training and another $5,000 bonus if they made the opening day roster. Their salaries were set at $115,000.

In early March the MLBPA announced that the players’ strike would not end if replacement players were used to start the regular season and stated that the results of any replacement games played must be voided.

The end came on March 31, 1995 when U.S. District Court Judge Sonia Sotomayor issued an injunction against baseball owners by upholding the National Labor Board’s contention that the owners had engaged in unfair labor practices. The strike was ended after 232 days on April 2, 1995, the day before replacement players were scheduled to open the season.

Per the terms of the injunction, the owners and players were bound to the terms of the previously-expired collective bargaining agreement until a new CBA could be agreed to. The 1995 season was postponed for three weeks and there would be an abbreviated 144-game season instead of the regulation 162 games.

There was a bitter legacy for the players who signed up to replace MLBPA players and crossed the figurative union picket line.

Many union players never forgave the players who signed up to replace them. Former San Francisco Giant Will Clark was later quoted in Newsday expressing his feelings about MLB Network’s Kevin Millar, who was a replacement player: “Kevin Millar was a scab,” Clark said. “There were 800 guys who chose not to cross the line.”

Baseball fans around the nation expressed their disgust with just about everything associated with the strike, which spoiled two MLB seasons and severely damaged America’s pastime. Stadium attendance plummeted and TV ratings nose-dived for the next several years.

The 1994-95 strike has often been compared to the 1919 Chicago “Black Sox” scandal (in which eight White Sox players were bribed by New York gamblers to lose the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds) in terms of the enormously negative impact it had on the game.

The emergence of Babe Ruth in 1920 went a long way to erase the baseball public’s bitter memories of the Black Sox scandal. And some baseball observers feel the damage done to baseball by the 1994-95 strike was repaired by the epic 1998 home run race between St. Louis first baseman Mark McGwire and Cubs right fielder Sammy Sosa.

Years later, that epic home run battle itself would be tainted by suspicions that both players used performance enhancing drugs, which McGwire later admitted doing including during the 1998 home run season.

The epic labor battles between Major League Baseball and the players’ union broke one of the strongest business monopolies in America’s history. In retrospect, the strikes and lockouts were likely unavoidable and a necessary growing pain. But it tested the sports public’s tolerance as millionaires fought billionaires for the heart of the game.

Amazingly the game itself not only survived, it eventually surged into a $11 billion enterprise that would have exceeded the wildest expectations of owners and players during the baseball labor war years.

In 2020, the loss of games due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the likelihood that some or all of a shortened season will be played in empty baseball stadiums is historic. But the game on the field has survived worse and will survive this.

Sources: Baseball Reference, Monthly Labor Review 1997, Sporting News, Newsday, Wikipedia (w/citations)

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!