3. Picking Off Three Runners for Three Outs: The Ultimate in Theft Prevention

Sometimes you find out that a cool, wildly unique baseball story isn’t quite what it appears to be. Turns out that events that seemed to be true, aren’t exactly true (even though you wish they were).

And the MLB media and fans have been known to sometimes ignore the facts and embrace the legend.

And the MLB media and fans have been known to sometimes ignore the facts and embrace the legend.

Like the fraud of the 1951 “Shot Heard Round the World” home run by the New York Giants’ Bobby Thompson. Or the following great baseball moment, whose imprecise description is more an innocent technicality than a deliberate obfuscation.

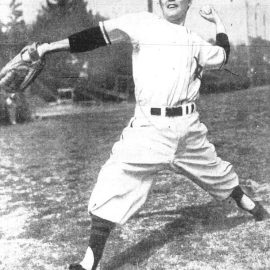

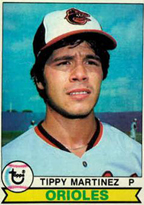

On August 24, 1983 Baltimore Oriole reliever Tippy Martinez sequentially picked off three runners at first base in the top of the 10th inning of a 3-3 tie game against the Toronto Blue Jays. Getting all three outs in the inning.

It all began with Oriole righty reliever Tim Stoddard starting the 10th for Baltimore facing Jays designated hitter Cliff Johnson. Johnson promptly planted Stoddard’s first pitch into the center field stands of Memorial Stadium and it was 4-3 Blue Jays before an extra inning out was recorded.

Stoddard then faced Jays right fielder Barry Bonnell who, on the third pitch he saw, laced a single up the middle putting a runner at first base.

Orioles Manager Joe Altobelli promptly yanked Stoddard and brought in Tippy Martinez, his lefty closer, to face right-handed hitter Jesse Barfield.

Orioles Manager Joe Altobelli promptly yanked Stoddard and brought in Tippy Martinez, his lefty closer, to face right-handed hitter Jesse Barfield.

Blue Jays Manager Bobby Cox countered by pulling Barfield for the switch-hitting Dave Collins.

Toronto’s Barry Bonnell was not a fast runner; in fact he would go 10-7 in stolen base attempts in 1983, a 62% rate, and his lifetime 64 steals in 103 attempts was a comatose 58% success rate.

So two things needed to happen for Barry Bonnell to get to second base without a hit or a walk.

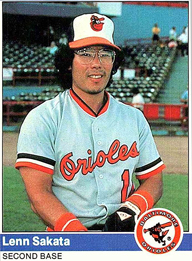

First, Bonnell had to take a near suicide lead off of first base to have any hope of stealing second base. And second, switch-hitter Dave Collins had to hit from the left side of the plate against Martinez, even though it gave the Oriole pitcher an edge in the at-bat battle. Because it forced Jays catcher Lenn Sakata have to look and throw around Collins in an effort to keep Bonnell close at first.

Although Tippy Martinez was not known for having a great move to first, he immediately took matters into his own hands and just as Bonnell started to move towards second Martinez threw to first baseman Eddie Murray, who chased Bonnell and tagged him standing flatfooted halfway to second base.

So here’s the deal. Tippy Martinez did pick Barry Bonnell off of first base, but once Bonnell committed to heading to second base it became an attempted steal.

So technically Bonnell was out on a “caught stealing” rather than a “pick-off”, and that’s what the box score shows. But Martinez did pick Bonnell off and that started the historic sequence.

In Dave Collins the Blue Jays now had a legitimate base stealing threat at first base. He would go 31-7 in steal attempts in 1983 (an 82% success rate) and in 1984 Collins stole 60 bases in 74 attempts (an 81% rate).

As Collins stood at first, the Jays’ Buck Martinez later related that first base coach John Sullivan leaned over to Collins and told him “Listen, you got one out, now don’t get picked off.” Seconds later, with Collins taking a huge lead off first, Tippy Martinez picked him off.

Now facing Willie Upshaw at the plate, Tippy Martinez threw a fastball that Upshaw smacked for an infield single to second base, so he took his turn at first. Again, as Buck Martinez relates, first base coach Sullivan walked up to Upshaw and said, “OK now you got two outs, you can’t get picked off now…”

Whereupon Tippy Martinez immediately threw to first base and picked Upshaw off.

Martinez ended up not

In the bottom of the 10th, after Orioles shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. homered to tie the game at 4-4 Lenn Sakata hit a walk-off three-run homer to give Baltimore the 7-4 victory. (And it’s interesting to note that this extra inning game took all of two hours and fifty-four minutes to play.)

With his three pickoff outs in one inning, Tippy Martinez did something no other player in the history of the game has done. And in the modern era where base stealing is no longer seen as a tactical advantage it may very well never happen again.

4. Ty Cobb Earns his Reputation as an Out-of-Control Bully

In researching Major League Baseball’s labor wars of the 1970s, 80s, and 90s I ran into the story of the first players’ walkout in the history of the game, which happened in 1912. But was that 1912 “walkout” actually a “strike”?

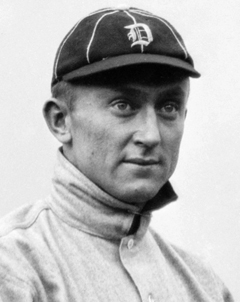

In April 1972 the MLB Players union staged its first organized strike against ownership with a 13-day shut-down of the game that forced MLB owners to give in to the union’s demands. The May 1912 action, on the other hand, was taken by the players of one team over a non-contractual issue involving their star player, outfielder Tyrus Raymond Cobb.

In 1912 Cobb played in 140 of the 154 games on the Tigers schedule, batting .409 in 609 PA and whacking 226 hits with a 200 OPS+. Cobb’s OBP was .456 and his SLG was .584, for a 1.010 OPS.

This followed a spectacular 1911 season in which Cobb put up a 1.086 OPS with 248 hits and 83 SB, earning the American League’s Most Valuable Player Award. To say he was a star doesn’t begin to describe his standing and his effect on early 20th century baseball.

Not known as an outstanding fielder, Ty Cobb nevertheless is second in MLB history with 392 outfield assists. In 1907 he turned 12 double plays from the outfield, in 1908 13 DPs.

But Cobb also had a notoriously hair-trigger temper. And on May 15, 1912 that rage would explode and reverberate throughout the American League.

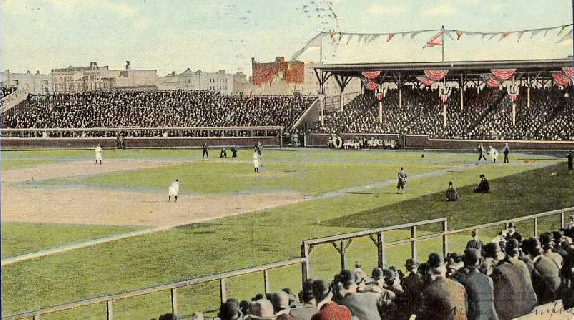

The Detroit Tigers came to New York to play a four-game set with the Highlanders (who would change their name to the “Yankees” the following season) on Saturday May 11, 1912. The Tigers’ lackluster 10-13 record was a depressing start to the season, and they had just dropped two of three at Boston to begin their current road trip.

After winning two of the first three games from the Highlanders, Detroit looked to take the final meeting on May 15th and leave Hilltop Park with a series win. Over the course of those three games, Highlander fans became increasingly abusive, much of the razzing directed at star center fielder Ty Cobb.

From the first inning of the Wednesday May 15th wrap-up game with New York, the home fans were heckling and taunting Tiger players. One fan sitting three rows up near the Detroit third base dugout focused his vocal attention on Ty Cobb.

Both the fan and Cobb freely exchanged epithets and according to the New York Tribune, “Bystanders declared that Ty gave the ‘fan’ ample warning of the impending assault but he refused to give heed.”

Things became so abusive that after the top of the 2nd inning Cobb didn’t return to the Tigers dugout, choosing instead to walk just outside a gate in center field and stand in the carriage parking area to avoid the abusive fan.

Cobb came back to the dugout before his next at-bat was due in the top of the 4th inning. The hectoring fan, one Claude Lucker who was later identified as a “Tammany Hall page”, upped the abuse, apparently shouting the racist taunt to Cobb that he was “half [n-word]”.

Detroit teammate Sam Crawford helpfully asked Cobb if he was “going to let that go.” Cobb responded by jumping into the stands and charging three rows up to where Claude Lucker was standing.

It turned out that Lucker was a disabled person, having lost one of his hands, and three fingers on his other hand, in a print press accident. In other words, Lucker had one hand, one thumb, and one finger. Cobb apparently grabbed Lucker, lifted him up and slammed him to the pavement, then he proceeded to stomp and kick him mercilessly.

It is reported that a nearby fan shouted for to Cobb to stop, saying “The guy has no hands!” Ty Cobb responded, “I don’t care if he got no feet” and continued the beating. When other fans moved in to separate the two men, several Tiger players who had followed Cobb into the stands with bats kept them at bay.

The NY Tribune would later declare that “[Cobb] was provoked into administering a well-deserved beating.”

Finally an umpire and a stadium policeman pulled Cobb away, and the Tribune reported that many fans cheered Cobb after Detroit won the game 8-4.

Cobb and his teammates were outraged over the fact that over-the-top fan taunting had been allowed by Hilltop Park security, and about the fine and suspension imposed on Cobb. It was reported by the Tribune that “a Pinkerton man [ballpark security]” had been standing near the abusive Lucker and took no action to stop him.

For his part, Claude Lucker later claimed in a May 19th interview in the New York Times that he “did not hear any one make a remark that was out of the way” during the game. He described how Cobb “vaulted” into the stands and “made straight for me”.

After being knocked down Lucker said “[Cobb] jumped on me and spiked me on the left leg and kicked me in the side after which he booted me behind the left ear”. Amazingly, Lucker required no serious medical attention.

In reaction to the American League punishing Cobb, Tiger players began openly talking about a strike and were reportedly contacting players on other AL teams to get their support.

On Thursday May 16th the Tigers had a travel day and boarded a train from New York City to Philadelphia to play a three-game series against the Athletics at Shibe Park. Amidst the continuing uproar over the Highlander game, the Tigers actually played the first game against the Athletics on Friday May 17th, winning 6-3.

Then things turned bad. Ty Cobb’s teammates sent AL President Johnson a signed letter noticing him they intended to immediately go on strike, stating “If the players cannot have protection, we must protect ourselves.”

A Philadelphia sports writer with whom Jennings was friendly helped him scour the streets of Philadelphia and put together a hodgepodge of amateur and semi-pro players who would be paid $25 each.

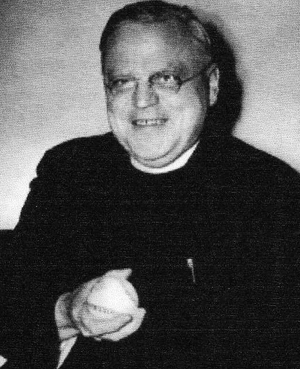

Notably among them was a twenty-year-old St. Joseph’s College seminarian named Allan Travers who opted to pitch against the Athletics because he would receive $50.

Travers later told NY Tribune/NY Times sports writer Red Smith that he went to the corner of 23rd and Columbia in Philadelphia “where a bunch of fellows were standing around”, all of whom became Detroit Tigers for a day. Travers also noted that he threw “slow curves” that day, because Manager Jennings told Travers not to throw any fastballs “as he was afraid I might get killed.”

Also joining the replacement team were Manager Hughie Jennings (43 years old) as a pinch hitter, and two of his coaches, Deacon McGuire (48) at catcher, and Joe Sugden (41) at first base.

Amazingly that game was played and is in the permanent record books as an official MLB game. The results will not be shocking: after 3 innings the Athletics led 6-0; after 5 innings, 14-0. The one hour and 45-minute contest ended with Philadelphia winning 24-2.

The replacement Tigers committed seven errors but managed to score two runs, and got four hits. Two of those hits were by 30-year-old C/3B Ed Irwin—and both were triples! Just four years later, Irvin died from injuries suffered when he was “thrown through a saloon window” in Philadelphia.

Once the replacement game was played there was a seriously compelling reason for Ban Johnson to step in and end the madness: if more players got the idea they could go on strike it just could precipitate the formation of a players union, and that could not be allowed. Ty Cobb also had enough, and he urged his teammates to end the strike and get back on the field.

In the end, AL President Ban Johnson fined each striking Tiger player $100, kept the $50 fine against Cobb and also imposed a 10-day suspension on the out of control Georgia Peach. The first players’ “strike” (or “walkout”) was over.

Go to “Four Intriguing MLB Stories I Can’t Get Out of My Head (#1 & #2)

Sources: Baseball Reference, New York Tribune, Jim Reisler/New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Society for American Baseball Research

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!