In the great swath of legendary MLB history and statistical oddities there are certain tales that grab us by the scruff of our necks, enter a special part of our brains, and refuse to leave the premises.

Here are four such stories for me.

“List” articles are seen as a lock to hook readers into clicking on your stuff. Because everyone likes lists:

“The Ten Best Pitching Performances in MLB History”,

“Top Twenty Power Hitters of the Past 100 Years”,

“Seven MLB Stadium Snacks You Don’t Want to Get on Your Shoes”, and “Three Compelling Reasons Not to Read this Column”.

And so on. I’d have to say it certainly looks like it works (right?).

1. Players Who Stole Second Base, Third Base, and Home in the Same Inning

If you had asked me a long time ago how many MLB players pulled off the seeming amazing feat of stealing second, third and home in the same inning of the same game I would have guessed, like, maybe a dozen.

In the words of Dom DeLuise from the film “Blazing Saddles”, “WRONG!”

Note that John McGraw and Mallex Smith were both 26 years old when they accomplished their around the horn steal-fests. McGraw would steal 73 bases in 1899, Smith 46 bases in 2019.

The AL’s Ty Cobb (1909, 1911, 1912, 1924) and NL’s Honus Wagner (1899, 1902, 1907, 1909) lead their respective Leagues, and the world, with four trifecta steals each. Max Carey of the Detroit Tigers (1923, 1925) and Jackie Tavener of the Pirates (1927, 1928) have two each.

Which innings, you ask, have the most steals of second, third and home in one inning? The favorite inning to pull this off is the 7th with 10 around the horn steals. The 5th and 6th innings are tied for the least with 2 each. There have been no triple steals in an extra inning.

There were 31 (58% of the total) around the horn steals in the same inning of the same game from 1899 to 1920; and 22 (42%) from 1921 to date.

But there is a big gap between the modern game and, to use a highly technical term, olden times.

After utility outfielder Harvey Hendrick of the NL Brooklyn Robbins (later the Dodgers) accomplished his around the horn steals on June 12, 1928 it didn’t happen again in the National League for 52 years, when 1B Pete Rose of the Philadelphia Phillies pulled it off on May 11, 1980.

Same in the American League. Jackie Tavener of the Tigers completed his base stealing magic act on July 25, 1928, and it would be another 13 years before 2B Don Kolloway of the Chicago White Sox did it again (June 28, 1941). And then another 28-year gap before the Twins’ Rod Carew accomplished it on May 18, 1969.

With the advantage of analytics we know that when a player attempts to steal a base it’s a high risk, low reward action. A “caught stealing” damages run scoring a lot more than a stolen base contributes to run scorning.

The traditional notion that a 70% successful steal rate is the acceptable cutoff is misleading. First, of course, there are a variety of contexts in which a steal is attempted, and not all contexts are equal.

Second, the massive upsurge in home runs over the past ten seasons further devalues any action that can cost extra outs— e.g., a stolen base attempt, sacrifice bunts. In 2010 4,613 homers were hit in the Majors; in 2019 6,776 homers left the building.

In today’s game, any unforced out is a missed opportunity to potentially hit a home run. Which scores runs and wins games.

In 2017, the Padres’ Wil Myers did it at home against the Phillies; and in 2018 Toronto OF Kevin Pillar accomplished it against the Yankees, again at home. Let’s hope it never disappears from the MLB scene.

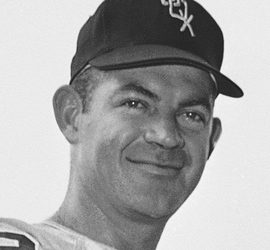

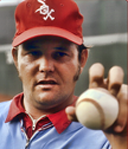

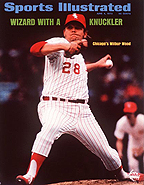

2. The Wacky Rollicking World of Knuckleballer Wilbur Wood

During the 1970s and 80s my favorite American League team was the Chicago White Sox. Don’t ask why, it’s a convoluted story about being very young and very baseball crazy.

In the late 1970s I even went on an adventurous road trip with a friend, driving from Santa Cruz, CA to Arlington, Texas simply to watch a White Sox game against the Rangers (and get ex-SF Giants OF Ken Henderson’s signature on a postcard).

This is yet another long story that also involved interaction with actual Texas Rangers after hitting 95 MPH on the I-20. But suffice it to say, mission accomplished.

It’s hard to explain what Wood’s pitches looked like but if you’ve ever laid a garden hose out on the ground and then turned it on full blast, that’s pretty close.

Take a deep breath here, because I’m about to reluctantly throw some pitcher “wins” and “losses” around now because that was the misguided measure by which pitchers at the time were evaluated. Today we know that pitcher wins/losses are useless stats and have virtually nothing to do with individual pitcher performance or value (in fact, they’re worse than useless because they’re also misleading).

So in the five year period from 1971 through 1975 Wilbur Wood “won” 106 games and “lost” 89 games. That’s 195 decisions in five seasons, an average of 39 per season. In 1972 he threw an unbelievable 376.2 innings, the most in the live ball era (i.e., since 1920).

Here are Wood’s pitching records over that period:

1971 — 22-13 / 1.91 ERA / 334 IP

1972 — 24-17 / 2.51 ERA / 376.2 IP

1973 — 24-20 / 3.46 ERA / 351.1 IP

1974 — 20-19 / 3.60 ERA / 320.1 IP

1975 — 16-20 / 4.11 ERA / 291.1 IP

In 1972 Sox starter Stan Bahnsen went 21-16 with a 3.60 ERA, and in 1973 Bahnsen went 18-21/3.57. So in 1972 the White Sox had two 20-game winners and in 1973 those same two pitchers were 20-game losers.

But 1973 was a singular season for Wilbur Wood, and an historic one for baseball. That season Wood won two ballgames on May 28th and then lost two ballgames on July 20th.

On May 28th Wood finished a suspended game against the Cleveland Indians, pitching 5 scoreless innings for the win. Then Wood started the afternoon game against the Indians and shut them out, giving up 4 hits and striking out 4. Totals for the day: 14 IP, 6 hits allowed, 0 ER, two wins.

On July 20th Wilbur Wood became the first pitcher in 55 years to start both ends of a MLB doubleheader– since the Reds’ Fred Toney in 1918. In the history of baseball a total of 103 pitchers started both ends of a double header– Wilbur Wood would be the last.

Wood faced the Yankees in New York and was shellacked in both games. He was pulled in the first inning of the opener after giving up six runs; in game two he only went 4 1/3 innings, giving up 5 runs. Two losses.

Wilbur Wood’s 17-year career numbers look amazingly good considering: 651 games played; 2,684 IP (an average of 158 IP/year); 3.24 ERA; 1.232 WHIP; 3.37 FIP; and 0.7 HR per 9 IP.

Wilbur Wood was a unique phenomenon and a late-20th century throwback to another time in the game’s history, one we can hardly imagine today. In memory of my time as a White Sox fan, I salute Mr. Wood and his uniquely quirky career!

Since these stuck-in-my-head MLB stories became longer to tell than I originally planned, I will have to continue my brilliantly-titled “Four Intriguing Major League Baseball Stories I Can’t Get Out of My Head” piece in a follow-up article.

Go to “Four Intriguing MLB Stories I Can’t Get Out of My Head” (#3 & #4)

Sources: Baseball Reference, Baseball Digest, Baseball Almanac

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!