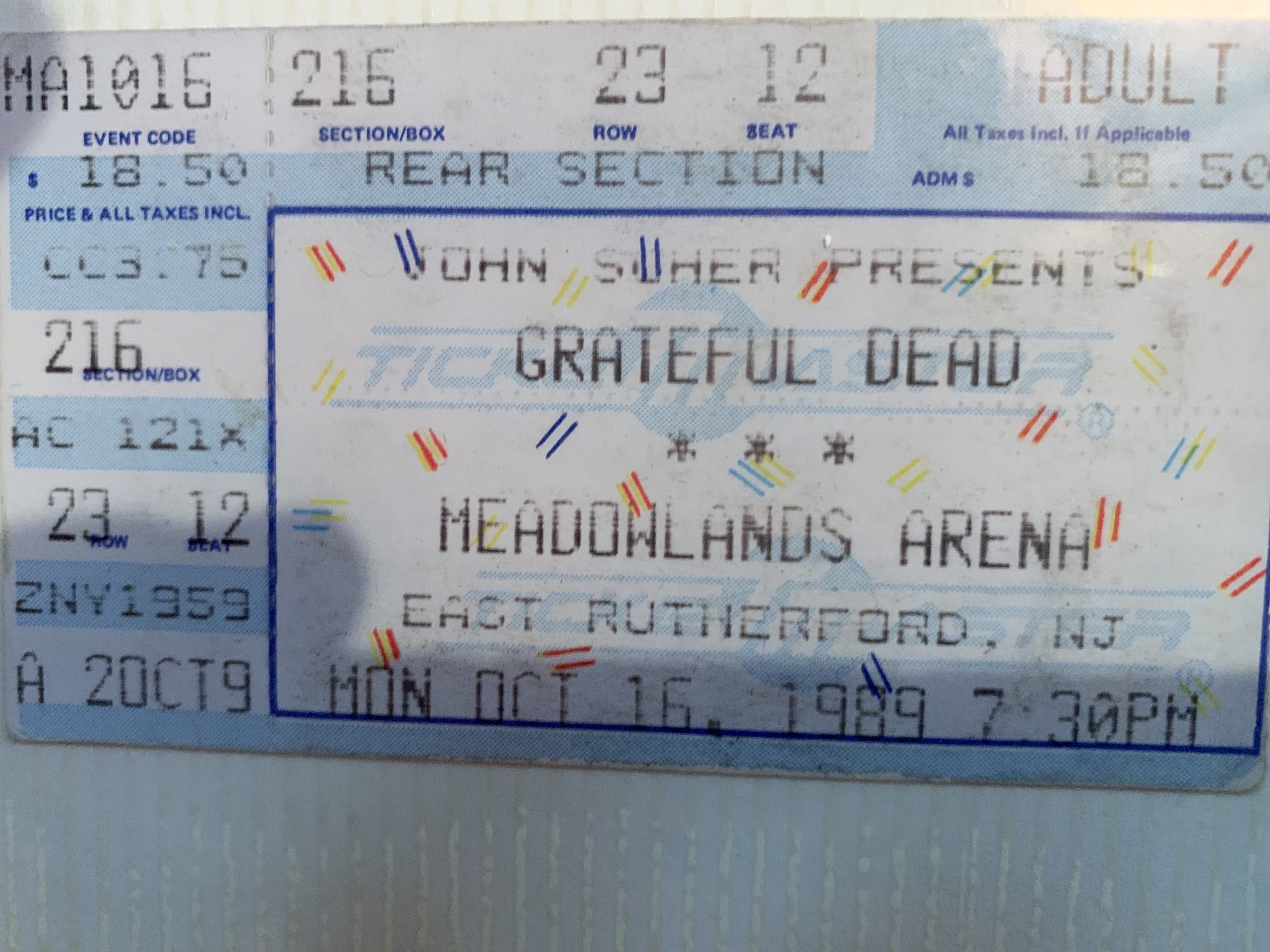

East Rutherford, NJ 10/16/89

I waited in anticipation while the band tuned up for the second set. Rather than teasing an actual melody as they usually did, Jerry began spitting out spacey notes from his guitar as Phil Lesh rumbled his bass underneath. It sounded like they were finishing one of their epic psychedelic jams from their early days. But when they stopped playing entirely and paused for ten seconds, everyone in that arena knew what was coming next. You could feel the crowd holding its collective breath.

DA DA DA DA, DA DA DA DA…

The eruption was deafening. I had never heard anything so loud at a Dead show. The closest thing I could compare it to was the roar from the Shea Stadium crowd after Lenny Dykstra’s game-winning home run in the 1986 playoffs. Undeterred by the booming ovation, Jerry Garcia immediately started soloing with a looseness and focus I’d never heard from him in person. By the fall of 1989, his white hair was in a pompadour and short ponytail that the Founding Fathers would have favored. Yet he was playing like he was twenty years younger, when the Dead would play “Dark Star” every night. But these were definitely not the carefree ‘60s. The freedom a Dead show represented to many, myself included, was in high demand in 1989. In the two years that I’d been seeing them, the crowds had grown so much that the Dead were running out of places to play. But on this night none of that seemed to matter.

1989 was one of the many turning points in the band’s thirty-year career. Two years earlier, the release “Touch of Grey,” from the album In The Dark, made them as mainstream as “the most outlaw band in the world” could ever be. They had a Top 10 hit, a music video, and were on the cover of Rolling Stone. The closest comparison that comes to mind was Springsteen during the Born in the USA period, except Bruce had always been bigger. The Dead always said that they wanted to have hit records, but were unable to capture the magic they conjured onstage in a studio. But while they may not have consciously shunned acceptance, they always did things their way, which is what made them so outlaw. They focused on their live shows, where they played a different set each night and improvised on almost every song. This undoubtedly cost them a chance at mass popularity, but helped cultivate the most devoted fanbase in music history.

But while “Touch of Grey” made the Dead mainstream if even for a moment, the crowd at the concerts was yet to be impacted. Attendees who would be derisively called “Touchheads” wouldn’t start popping up at shows until the following year. I should know, since my love of the Grateful Dead coincided with the phenomenon created by their “hit single” in the Summer of 1987. I was a waiter at Camp Baco in the Adirondack Mountains at the time, a kind of way station before coming a full-time counselor. Waiters had the best of all worlds at Baco. They were idolized by all the younger campers, but old enough to socialize with the counselors. Plus, actual dining room work only took up the mornings, so there were tons of unstructured free time to get into all sorts of mischief.

Many attendees of Northeastern summer camps and prep schools became breeding grounds for Deadheads and Baco was most definitely one of them. The Dead were not only the thing that connected so many of the staff that hailed from different backgrounds and locations. It was also the way they stayed in touch during the year. Counselors traded live tapes through the mail and met up at shows on the band’s annual fall and spring tours. My exposure and acceptance of the Dead had been building since the previous summer, when Jerry Garcia had fallen into a coma. Deadheads nationwide, as well as those at Baco, held their collective breath as Jerry lay unconscious for five days due to complications from his diabetes. Of course, his years of drug abuse, cigarette smoking, and poor eating habits combined with zero exercise were all underlying factors. After emerging from his coma, Jerry had to completely relearn the guitar. When the Dead finally returned to the stage five months later in front of their home crowd at the Oakland Coliseum on December 15, “Touch of Grey” was the first song they played. The chorus of “I Will Get By/I Will Survive” took on an entirely new meaning. Those in attendance said there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.

The Dead recorded the song, and the rest of the In ihe Dark material, at the Marin County Veterans Memorial Auditorium the following month. After previously failing to get acceptable studio versions of these songs for the last five years, they tried an entirely new tack. They played onstage as if they were at the Oakland Coliseum (or any live venue) in front of a raucous crowd. It was the most the band ever sounded like themselves on record. The combination of the songs, the approach, and the renewed energy of a post-coma Jerry Garcia caused the Dead to strike gold (platinum, more accurately) with In the Dark.

The Spring Tour of 1987 was filled with good vibes as the revived Grateful Dead played in front of euphoric crowds that feared they’d never see them again. But those that only knew the band from “Touch of Grey” weren’t showing up yet at concerts. The massive influx of ticketless fans who came only for the legendary parking lot party scene came later. I’m not sure if the “Touchheads” were really every influenced by the success of the song to begin with.

To accommodate the crowds and expose the group to new fans, several shows on the Spring ’87 tour were broadcast on FM radio. I was still not indoctrinated enough to see them live, but was tasked with taping one of their shows at the Meadowlands Arena in East Rutherford, New Jersey. Both Giants Stadium and the Meadowlands racetrack were located next to the arena and the entire sports complex was often referred to as “The Swamp,” since it was actually built on a marsh. It was no surprise that Clemenza had Rocco Lampone leave the gun and take the cannoli after shooting Paulie Gatto out there in The Godfather. He sold out the Don, so being left in the reeds seemed like an appropriate fate for him. There was also an urban legend that missing Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa had been buried in one of the end zones of Giants Stadium. When the local teams endured many dark periods during the 1980s, people would joke that at least someone got into that part of the field.

A kid from my Spanish class at Horace Greeley High School in Chappaqua gave me two Maxell XLII 90-minute tapes and asked if I’d do him a huge favor. He was going to the April 7 show and asked if I’d record the broadcast on the legendary WNEW 102.7 FM. As I made sure to flip the tapes on time to capture the entire show, I listened to only part of it. I still wasn’t fully hooked on their music and this wasn’t their greatest performance. Listening now, they were energetic but were still in the process of readjusting to each other on stage. The crowd didn’t care; they were just ecstatic to be there again. Plus, they were adding the edgy jolt that only came from a metropolitan New York area audience. This would often bring out the best in the Grateful Dead when they came east.

I’d soon realize that first hand when I finally attended the first of my 138 Dead shows on September 18, 1987. These were the band’s first Madison Square Garden shows since 1983. They had been playing the Metro New York area at the Meadowlands and Nassau Coliseum on Long Island. However, once they found out that the Coliseum was basically becoming a sting operation for drug busts they stopped playing there. The ’87 Garden shows were also their first five-night stand in New York since the 1970s. Legendary producer Clive Davis, whose decision to sign the Dead to Arista in 1977 was finally paying off, attended the first show. He couldn’t believe that they didn’t play “Touch of Grey” now that it was a bona fide hit. Jerry, true to form, told him that they forgot and they opened the second set of the second night with it. On their off night, Jerry and Bob Weir appeared on Late Night with David Letterman. He’d previously had Jerry and Bob on during the 1982 Nassau Coliseum shows and gave them even more screen time for this appearance. The episode opened with a genius bit with him and Jerry playing Scrabble.

That Friday night at the Garden ended up being one for the ages. It is universally lauded as the best show of the year and one of the standouts of the entire decade. On the very same day when In the Dark was certified platinum (it would sadly go double platinum on the day following Jerry’s death in 1995), the Dead laid down a performance that defined what they were really about. I had nothing to compare it to, but the crowd’s reactions and comments reminded me that I was seeing something special. Bob Weir’s opening joke about “levitating Garcia,” a reference to the parlor trick he tried on Letterman the night before and they opened with a raunchy “Hell in a Bucket” the only song from the “new” album. They dropped into “Sugaree” and I knew I was hooked. They didn’t introduce a single song, but the crowd recognized each one within a few notes. They looked like they were all soloing at once, even though. Jerry’s guitar was undoubtedly the catalyst. But every time his playing caused the Garden crowd to explode, his only response was to push his glasses back up the bridge of his nose and keep going.

The second set began with Jerry’s fingers running up and down his fretboard to signal “Shakedown Street.” As a roar came up from the audience, both drummers erupted with a sound like a series of firecrackers.

WOOWWWWWWWWWWWWHHHHHHH

Jerry’s guitar started the set in earnest. My Baco buds Stoney and Rose, joined me slackjawed as a massive spotlight panned across the crowd. The song sounded like “Disco Dead” when it was recorded back in 1978, but on stage, they had boiled it down to its essence. It was a funky, yet sinister bad ass.

But it was the version of “Morning Dew” they played about an hour later that really made the night epic. Jerry may have looked like Santa Claus by 1987, but he sang this ballad with all the emotion of a screaming child. You could tell by the looks of the other band members and the shrieking crowd that he didn’t get this raw very often. His solo was even better, as he poured even more emotion into the notes than the words. There were times that it even sounded like the guitar cracked like a creaky voice from being played so fast. This isn’t just hyperbole. This version of “Dew” is universally considered to be one of the best ever. In fact, the show was later released in the career-spanning box set that featured one concert from each of the band’s 30 years. Needless to say, I picked one hell of a night for my first show.

The following spring I saw my second show out at Meadowlands Arena. It was almost a year since I’d taped the radio broadcast of their last visit there. This was the first time I got to experience the infamous “lot scene” at a Dead show. I didn’t get to hang out for very long, as it was a school night and I was driving my parents’ Volvo. But I was able to buy a beer and snag a wildly unlicensed shirt. It was a Monopoly parody with all the spots on the board named after Dead songs. The show that night was really good, but not like the Garden show. The “show of the tour” turned out to be in Hampton Coliseum a few nights earlier. I would soon learn that part of the Deadhead experience was chasing “the show.” Little did I know I would find it in the same building the following year.

I was fortunate enough to catch another fantastic one that summer at the Saratoga Performing Arts Center. SPAC was very close to Baco and the concert turned out to be on the night before the campers were set to arrive. Many of the counselors went and I was fortunate enough to score balcony seats for Stoney and Rose as well. We’d then avoid being among the 20,000 on the lawn. Actually, there were far more on the grass that night. The Dead had already packed in a record 40,000 on their last visit in 1985. SPAC was the perfect place for the band. It was scenic, had great sound and had clear sightlines. It also had lots of nooks and crannies for people to get into trouble. Bob Weir and bassist Phil Lesh had to publicly admonish a guy for hanging off the balcony in the middle of the show. It was no surprise that the band didn’t play there for two years after.

1988 was the last time the Dead could play amphitheaters and “sheds” exclusively on their summer tour. Summer was when the parking lot scene was biggest and the 1988 show was the last time they would ever play SPAC. I don’t know how many people snuck past security or whether there were an abnormal number of incidents. I can recall looking out during an epic “Fire on the Mountain” and seeing way more than 20,000 people bobbing back and forth.

By this time it was “the scene” that was making it harder for the band to perform. In the words of their publicist and historian, Dennis McNally, vending and camping were killing the Grateful Dead. More people than ever were showing up to commune, party, or vend everything from sandwiches to shirts to drugs. People would show up without tickets and stay in the lot if they couldn’t secure one. For some, Dead tour was becoming a right rather than a privilege. They wouldn’t pay for the ticket but instead demanded it be “miracled” to them. By 1989, venues like the Hartford Coliseum, Worcester Centrum, Providence Civic Center, and Hampton Coliseum were no longer welcoming the band for their annual spring dates. This undoubtedly led to the decision to try some places the band hadn’t played in a while.

But since Pittsburgh was the only Northeast stop on the tour, thousands more descended on the city than usual. There were about 500 reported gate crashers and the police responded with mace, night sticks, and arrests. The riots were all over the news as the shows looked more like the 1968 Democratic Convention than a rock concert. A band that prided itself on not telling its fans what to do or how to behave was now in the position of having to do just that. The Grateful Dead, and Jerry Garcia in particular, weren’t about to lecture Deadheads on the perils of drugs. But the one thing Deadheads all cared about was future shows. Many of the people showing up in the lot were professional dealers or others who didn’t share their concerns. After the riots in Pittsburgh, sting operations like the ones the cops used to run at the Nassau Coliseum shows were soon to be common in the parking lot. As Dennis McNally put it, “Jerry Garcia didn’t sign on to be the de facto mayor of a travelling city.”

The East Coast portion of the 1989 summer tour was therefore relegated to stadiums. The previous year’s shows with Dylan were one thing. This was the Grateful Dead as headliners and the only way to see them was in an 80,000 seat stadium with Jumbotrons. This was also the first tour where camping overnight was outlawed and vending heavily scrutinized. The band was playing better in 1989 than at any point since Jerry’s coma and I drove down from Baco with Stoney and Rose to catch the first of the two at Giants Stadium. You can hear how good it was on the freshly released 14 CD boxed set that highlights three years of shows there. They opened on July 9 with a fiery “Shakedown” that got everyone up and dancing. But you have to look at the photos in the liner notes for evidence of the cheers showered on hundreds of fans as they jumped onto the floor section. From my perch in the upper deck, I remember feeling more than a little squeamish as I saw people undoubtedly breaking their ankles just to get down there. As it was at the Garden two years previous, the funkiness of “Shakedown” was the perfect soundtrack for the already edgy New York crowd. But this felt like something darker, almost sinister. I had a great time that night but couldn’t shake the image of all those ant-like figures descending onto the floor.

The penultimate show was in a new (to the Dead, anyway) amphitheater, Deer Creek in Indiana. That was reportedly a great venue and show. The final three dates were at Alpine Valley in Wisconsin, which the band had been playing since the early ‘80s. The Alpine shows were some of the best of the tour, but these would be the last ones the Dead would play there. This was beyond the vending and camping problem. They had just gotten too big for these places. By the end of the summer they would also play their final shows at hometown venues like the Frost Amphitheater in Palo Alto or Greek Theatre in Berkeley that had been yearly tour staples.

But the Jerry’s post-coma energy had spurred the rest of the band new heights. Even in those massive stadiums, the band sounded as good as they had since the 1970s. The plethora of official of both audio and video releases bear witness to this. All the band members seemed relatively healthy, save for keyboardist Brent Mydland. He had been in the band longer than any other keyboardist before him, but still felt he was seen as the new guy by the audience. The fact that the two previous keyboardists, Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and Keith Godchaux, had died only added to the darkness surrounding him. By 1989 he had a series of alcohol-related arrests and had spent time in rehab in an attempt to clean up. However, he also poured his pain into his on-stage performances. His gravelly vocals and soulful playing were a highlight for many Deadheads, despite his own insecurities. Often times it was Brent that Jerry would appear to be locked into each other onstage more than anyone else. They played off each other and the resulting performances became that much stronger.

The only complaint one could have (Deadheads, like many obsessives are always looking for one) was that the band’s sets were missing many of the exploratory elements and songs that had marked the late ‘60s/early ‘70s. But since the spring tour, Jerry Garcia began experimenting with the then-new MIDI (Musical Instrument Digital Interface) technology. This allowed him to substitute his always-recognizable guitar tone with the sound of a flute, trumpet, or pipe organ. At first, he had a special guitar, a white Fender Stratocaster, for the MIDI effects and he exclusively used it during the nightly “Space” segment that that followed the drummers’ solo. But by the end of the summer, he broke out his infamous Doug Irwin guitar with the cartoon of the wagging tongue Wolf at its base. This was the guitar he’d played from 1973 to 1979 and hadn’t been seen since. For the shows at the end of September at Shoreline Amphitheater in California, Jerry was playing “Wolf” for the entire show with his MIDI pickup crudely hooked up with black electrical tape. Simultaneously, the band played the old Reverend Gary Davis song “Death Don’t Have No Mercy” for the first time since 1970. They had already broken out the gospel acapella standard “And We Bid You Goodnight” at the first Alpine Valley show. These were songs that marked the great shows of the psychedelic era the band was born from. The stars were aligning for something big in Deadlead—a Dark Star.

What kind of song could inspire this sort of meticulous reconstructing? Jerry was working out the chords of “Dark Star” in May of 1967, right before the “Summer of Love” overtook San Francisco. Hunter overheard the jazzy chords the band was rehearsing and wrote the haiku-like lyrics shortly thereafter. He always referred to “Dark Star” as the first song he wrote for the Grateful Dead. The studio version recorded a year later is a little over two minutes, unimaginable for a song whose longest version is 44 minutes. Sadly, it contains Robert Hunter’s only vocal appearance on a Dead record as he speaks an additional verse over an old recording of Jerry Garcia playing the banjo to end the song. Even in its infancy, “Dark Star” had little Easter eggs buried in it for the faithful.

Hunter, who passed away at 78 on September 24, was always especially evasive about the meaning of his songs. It wasn’t always easy for him to watch Jerry become Jerry while singing his words. In the epic four-hour Scorsese produced documentary Long Strange Trip, director Amir-Bar Lev, with the help of Bob Weir, tracks Hunter at Manhattan’s City Winery to get him to answer one question. Playing off his curmudgeonly reputation, he sarcastically recites the lyrics while a live version from the Fillmore East provides the soundtrack:

Dark star crashes, pouring its light into ashes.

Reason tatters, the forces tear loose from the axis.

Searchlight casting for faults in the clouds of delusion.

Shall we go, you and I while we can

Through the transitive nightfall of diamonds?

“What is unclear about that? It says what it means.”

Even though he might have been joking at least a little, that line serves as a perfect epitaph for Hunter. His intentionally enigmatic lyrics create set the stage and the open-ended nature of the song that allowed it to become the ultimate improvisational vehicle for the band. He was right that it was the band’s performance of the song that encompassed everything the Grateful Dead was about. It was as free-form as rock music could be. The appeal of the Grateful Dead for so many fans was that no two shows sounded the same. This was doubly true for “Dark Star.” The closest comparison would be different versions of Miles Davis’ “So What” or John Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things.” 1969’s “Live/Dead” finally allowed the band to commit their unmistakable psychedelic sound to record and the 23-minute “Dark Star” that opened it was the highlight. Robert Christgau of the Village Voice called it “the finest rock improvisation ever recorded.” Back then, the band was playing it every night. By 1970, it became less frequent. After their year long hiatus in 1975, the song didn’t reappear in the repertoire. They broke it out for the closing of Bill Graham’s Winterland Ballroom on New Year’s Eve, 1978. A fan-made banner read “1,535 Days Since the Last S.F. Dark Star,” was already hanging in hopes that they would revive it that night. They only played it twice in January of 1979 and then only broke it out for similar special occasions. They pulled it out on New Year’s Eve 1981 and encored with it on Friday the 13th of July, 1984 at the Greek Theatre. Jerry had been coy in recent interviews about whether the band would ever play it again. But as his friend Ken Kesey used to say, you just never trust a prankster anyway.

The Dead had been working on the follow up to In the Dark for over a year and Arista thought it would be a cool promotional tool for them to release it on Halloween. They were printing up posters and stickers with a skull on top of a pumpkin that read “On Halloween The Dead Will Rise Again.” Jerry said it was a little corny, but the fall tour would begin in October to coincide with the release Built to Last.

Rather than play the Garden, the Dead were back at the Meadowlands Arena again for five nights. There were two weekday shows, with an off day on Friday the 13th. The stand would end on a Monday, which was Bob Weir’s 42nd birthday. It sounded like kind of show not to miss, but my parents weren’t yet willing to let me miss classes for the Dead. Fortunately, the city of Rochester (and big donor Bausch and Lomb) were sponsoring the first Regatta Weekend for collegiate rowing crews. I didn’t care about the crew team, but the school was giving us a three-day weekend. I couldn’t have been the only Deadhead to make this decision since the crew team began selling fundraising shirts with a boat and oars in the middle of the band’s “Steal Your Face” skull. This was the first stop on the fall tour and the final Jersey shows would hopefully be the ones to hit.

Then the surprise shows in Hampton (VA) happened. A kid on my freshman hall told me that the Dead were playing two “secret” shows at the Coliseum, from which they had been banned, under their original name, “The Warlocks.” To make sure they could keep their return secret (and I’m sure a condition of the venue), tickets would only be sold locally. This still sounded too fantastic to be true. The kid who told me wasn’t even a Deadhead; he got the tip from his brother back in Virginia. I couldn’t even get down to Hampton if rumor turned out to be true. At least that’s what I told myself when I found what went down. It wasn’t until the day after the second Hampton show when I heard the news. I was walking through the quad in front of the library when a kid I started trading tapes with filled me in. Not only had the band played these two “stealth” shows, but they had limited the ticket sales to local outlets to keep “the scene” from descending on Hampton Coliseum. They were billed as “Formerly The Warlocks” and the setlists and subsequent performance made both shows instant classics.

On the first night, they opened the second set with the first “Help on the Way” in four years and played “And We Bid You Goodnight” again. On the second night, they finally played “Dark Star.” I wouldn’t hear a tape of the show for a couple of months, but the first audience recording that surfaced revealed the loudest crowd reaction I had ever heard. The music was instantly swallowed by the roar of the audience. Jerry used his MIDI on “The Wolf” to fully jam out the song for 20 minutes, the longest version since the band was playing it semi-regularly in the early ‘70s. People called their friends that night and only had to tell them that the band had played “IT” and it was really, really good.

As if that wasn’t enough, they played “Death Don’t Have No Mercy” again out of “Space” and encored with “Attics of My Life.” They had only played “Attics,” recorded for 1970s American Beauty, a handful of times ever which made it an even more unlikely candidate to be revived than “Dark Star.” These were songs that only appeared on Deadheads’ “fantasy setlists.” They sounded like what they would play if they were planning on never performing again. Fortunately, they started the “proper” tour dates after a day off from the Hampton shows.

But were these just “one offs?” Had the entire secret operation to get the band to Hampton meant that these songs were only for those who had the faith to be there? Rumors had even hit Rochester that the second show was so great because it would have been John Lennon’s 49th birthday. The first two shows in Jersey were reportedly strong, but had none of the “busts outs” of Hampton. I drove down from Rochester on Friday the 13th, just in time to see Bobby and Jerry perform on David Letterman again. Rather than play a song from their forthcoming album (or any album, for that matter) they covered Smokey Robinson’s “I Second That Emotion.”

My girlfriend and I got to the parking lot early the next day. The last time I was at the Meadowlands, I didn’t really get to soak in the scene since I had high school the next day. People were still buzzing about Hampton, but there also seemed to be some darkness in the lot. It seemed like people were partying a little harder and that the cops were keeping an extra eye on them. The Saturday show started with “Touch of Grey,” which had fortunately lost its mainstream luster. The band sounded great, but I couldn’t help wonder if anything from Hampton would be repeated again. Was the band going back to “normal” setlists? Would it be impossible to really enjoy a show knowing what they wouldn’t be playing?

I still remember telling my girlfriend after a few songs how cool it would be if they played “Help on the Way” to close out the set. I never thought they would, but was simply hoping. When they launched into it, the crowd erupted. Now we knew that Hampton wasn’t an isolated incident. The ensuing “Slipknot!” jam segued perfectly into “Franklin’s Tower” as bliss swept over the crowd. After the last of Jerry’s screaming pleas to “Roll Away the Dew,” the band left the stage to thunderous applause.

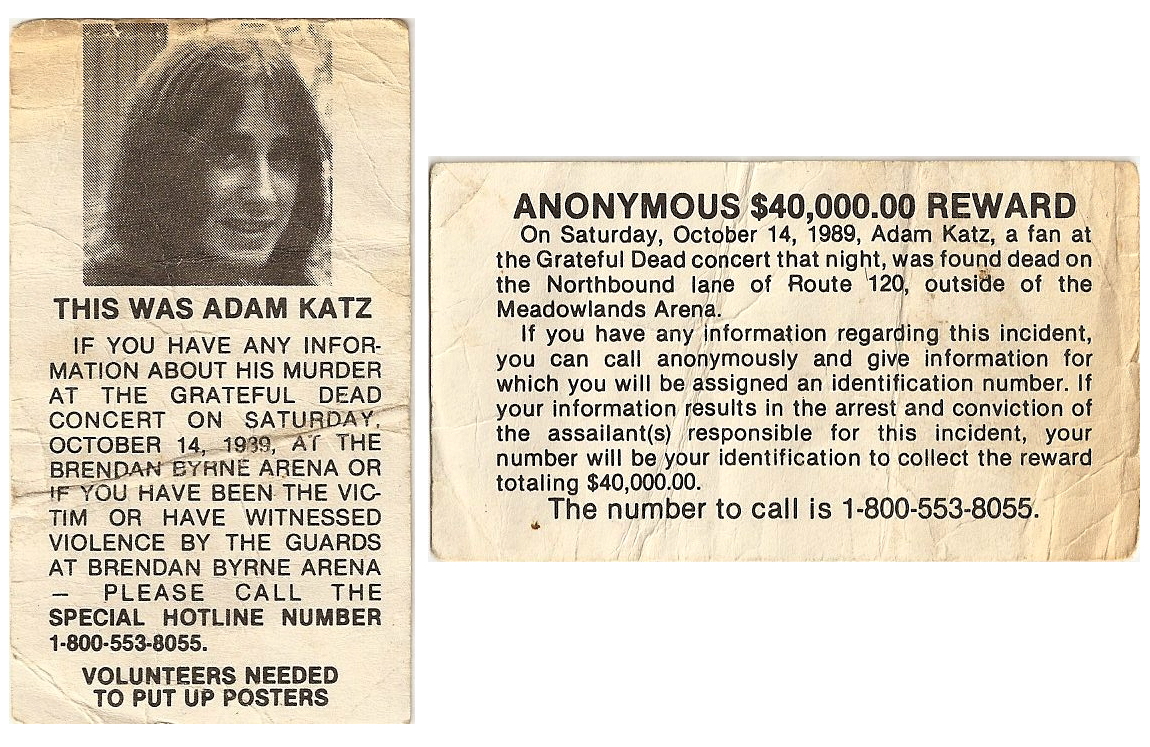

The second set was also strong, but everyone was not only fixated on what they had played in the first set, but what might be coming over the next two nights. Since we had come early, we didn’t have to cross the pedestrian bridge that led to the Giants Stadium lot upon leaving. If we had, we would have been met with the yellow jacketed security guards telling people that the tunnel was closed. It wasn’t until the morning after the Sunday show (good, but no songs from the Hampton batch), that my mom told me that a kid had died outside the arena that night. It was reported at the time that he was just another kid tripping on acid who had fallen to his death. Investigations and lawsuits would follow in the years to come and while the truth was never fully disclosed, a lot of disturbing details emerged. Forensic evidence would suggest that he was killed with a blunt instrument and transported by van to an overpass where he was thrown 20 feet onto Route 120. By Monday, flyers appeared with the picture 19 year-old University of Hartford student Adam Katz. Katz was from South Orange, NJ and his family’s flyers would be handed out on tour over the next few years. There was a $40,000 reward and an 800 number to call. These flyers were constant reminder that the Dead scene was changing as the crowds outside the shows grew and grew.

As I got ready to leave for the Monday show, my mom reminded me to “use my noodle.” I wasn’t going to be tripping and didn’t have long hair, but this kid didn’t seem all that different from me. He was just another Deadhead from college going to hear his favorite band and he died at the hands of the Meadowlands thug squad. The Giants played the Redskins the afternoon of the Sunday show and it seemed like there was way more drunken debauchery in the parking lot than the adjacent one at the arena. However, I tried to focus my energy on the final show. Were they going to play “Dark Star” again? I didn’t know that Jerry was on WNEW with legendary DJ Scott Muni who asked him the same question. If I had known, I would have heard his response that it might happen “sooner than you think.”

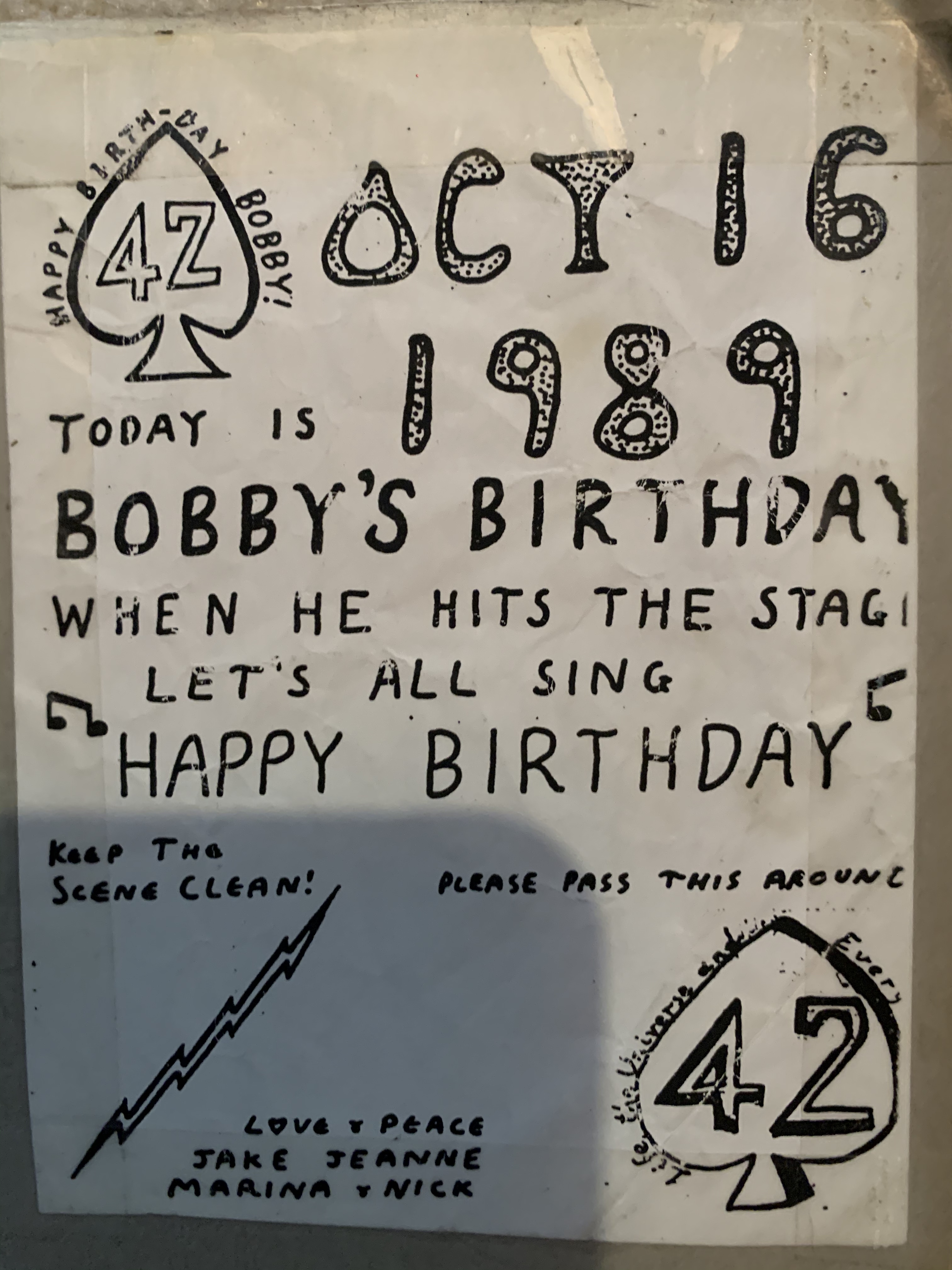

At that point I don’t know if anticipation could have been higher for Monday night. On our way in to the arena that night, we were handed small flyers reminding us to sing “Happy Birthday” for Bob Weir at the start of the second set. The show opened with “Picasso Moon,” one of his new songs that would appear on the new album due out in couple of weeks. It wasn’t anyone favorite and the band was still in the process of working it out on stage. Back then it sounded like a poor man’s “Hell in a Bucket,” but you could tell that they were really fired up. It already felt like it was going to be a special show.

“Mississippi Half-Step” was often a show-opener, so it was surprising to hear it in the second slot. Jerry, still playing his “Wolf” guitar, was in strong voice as he belted out the lyrics. The solo sounded extra fluid, which is saying something given how liquidy Jerry’s guitar tone usually was. We were all surprised when instead of singing the songs closing refrain, the band came to a complete stop. I guess this was a “Mississippi Quarter Step.”

But when they launched into “Feel Like a Stranger,” no one cared a bit. This was another song that would often open a show, so we felt like we were getting a bonus. Phil Lesh’s bass was pumping through the arena to give the backbone for the song’s funky beat. When Brent sang “It’s gonna be a long, long, crazy, crazy, night,” Bobby replied with “I believe he’s right.” The jam, so often the twin brother to “Shakedown,” held the perfect mix of exploration and danger. These two themes would come to personify the entire evening. Jerry’s guitar snarled and swirled until he was ready for the rest of the band to help him stick the landing.

Next up was Brent’s “Never Trust a Woman,” an original blues song that was never recorded for an album. The band had been playing it since 1981, and many Deadheads viewed it as more than a little cheesy. However, they were playing the shit out of it and Brent seemed especially assertive. When he sang “Come tomorrow, I’m gonna take my pay and leave this fuckin’ town,” it sounded like he meant it. We all had heard that his drinking had let to some domestic issues with his wife and daughter, but the lyrics also echoed the actions of Meadowlands security over the weekend.

“Built to Last,” the title track from the new album, provided Phil Lesh a rare chance to provide harmony with Jerry, but was the lone song that fell flat in the set. Jerry used his MIDI effects to replicate the high octave of the piano and then the horn, but the tune never quite came together. The band would only play the song two more times after that. So much for naming the album after it.

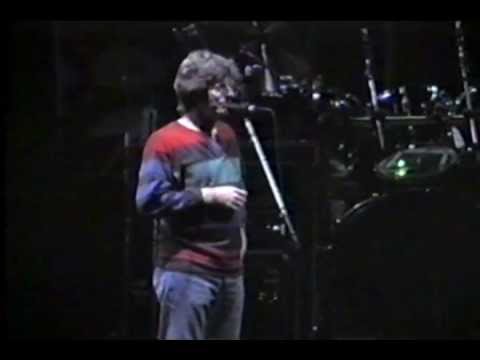

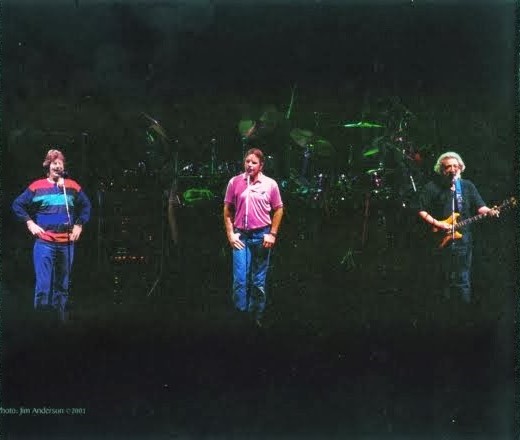

Bobby, in his pink Polo shirt and jeans, clearly wanted to celebrate his 42nd and led the band through a powerful cover of Bob Dylan’s “Stuck Inside Of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again.” Deadheads always pointed out that he could remember the countless verses to a Dylan song but not his own compositions that he’d been singing for close to thirty years; he’d gotten lost in “Truckin’” countless times. This was the first time I’d heard the Dead do “Memphis Blues,” but I knew it was a great version. Each verse built as Jerry and the birthday boy increased their ferocity. After the song was over, Jerry started plucking the notes to “Happy Birthday” and the crowd followed with a sing-a-long. As if to signal that this was his present, the band began “Let It Grow.” They rarely played two Bobby songs in a row and they made this one count. The Spanish-themed jam ripped through the arena and hit some amazing peaks. During one of them, I heard the sound of a flute coming to my left. Jerry had already used the MIDI horn tone from his guitar, so I had no idea where it was coming from. My girlfriend and I both turned in unison and saw the girl next to us jamming along with a flute. I don’t know how she got it into the arena, but it really wasn’t needed. But Jerry was tearing up his solo so much, I just let it go. Plus, I wasn’t about to ask someone to put away their woodwind instrument during a Dead show.

It seemed like a foregone conclusion that this would be the end of the set. “Let It Grow” usually was and they played this version like it would be the closer. So we were all floored when Jerry started the chords to “Deal,” also usually a set ender. Now they had played four songs that usually bookended the first set. They hadn’t played these two songs consecutively since 1985 and this “Deal” tore the roof off. Jerry showed off his entire repertoire with his solo. Each time you thought he’d hit the highest peak possible, he’d push it just a little bit more. When the band finally joined together to remind us all not to let that deal go down, we knew this was already shaping up to be a special show.

As I walked around the arena, you could feel the satisfaction and frenzied anticipation in the air. They had to play “Dark Star” in the second set, right? As if to remind of what might be to come, there were shirts for “The Warlocks” on sale at the concession stands. I also saw some parking lot shirts from the Hampton shows with the lyrics from “The Music Never Stopped” on the back.

“No one’s noticed, but the band’s all packed and gone/Were they ever here at all?”

It seemed like they definitely brought their magic from those “secret shows” with them. I thought the best way to start the second set was to open things up with “Dark Star.” It was a long shot, I knew. They hadn’t done that since 1971, but it seemed like anything could happen on this night. When they came back onstage, their intentions were made immediately clear. Instead of tuning up as usual, Jerry ripped off a few spacey bars. It was these 30 seconds that John Oswald chose to open the Grayfolded album with. The band paused which made sure everyone knew what was about to happen.

There was sense of purpose in Jerry’s solo as his fingers ran up and down the fretboard. Rather than noodling, this “Dark Star” somehow had focus and freedom. I’d hear after the show that people were lined to at the pay phones to tell their friends what they were missing, just as they were in Hampton. I have no idea how the people on the other end could hear them, but I’d like to think it was like Chuck Berry getting that call from the “Enchantment Under the Sea” dance in Back to the Future. It felt like Jerry had the entire arena in the palm of his hand as he took the band in every possible direction. When he stepped up to the microphone to sing the first verse after about six minutes the crowd exploded again.

The audience response was so intense that I wasn’t surprised when Jerry turned to face his speaker. However, he kept climbing and winding with his solo. I looked at the threadbare seats in front of me and thought for a moment that people might actually be able to rip them out. They certainly had the energy for it. Things started getting really spacey after another six minutes or so, they came back to earth just in time to go right into “Playin’ in the Band.”

This was another song that was often used was a jumping off point for long explorations; they once did a 45-minute version of it. The crowd was so appreciative for what they’d already experienced and you could feel the band feeding off the energy. The solo was so deep that no one seemed to notice that they’d only done the first verse of “Dark Star.” Even though it had been “only” about 12 minutes long, they’d made every note count. When it seemed like Jerry had reached the edge of the sinister theme he’d been playing with, he began strumming the happy opening chords to “Uncle John’s Band.”

Like “Playin’,” this was song they’d played countless times. But on this night, it sounded brand new. They sounded so good that no one cared when Jerry sang the wrong verse at one point. Bobby, who’d met Jerry at age 15 when he was giving banjo lessons, still looked like the little brother in the band. Even at a freshly-minted 42 years old, you could see him beaming at Jerry as they sang “Wo-oah, what I want to know, where does the time go?

The parting jam was so intense that I wondered what song they’d play next. Rather than start one, they began flirting with “Playin’” again. The ensuing jam was even longer than the version of the song they had just played. It was as exploratory (and as long) as “Dark Star” as it bobbed and weaved. The first half of the show had essentially been one long amazing song. By the time the stage was left to the drummers for their nightly solo, it sounded like the band was trying to land a spaceship. In many ways they were.

During “Space,” I couldn’t even predict what they might play. The setlist didn’t follow any pattern and this was already the best show I’d ever seen. I didn’t even care what came next, but I was surprised when Jerry began using his MIDI for horn effects and Brent began pounding out chords. “I Will Take You Home” was probably the last song I expected them to play at that point. It was essentially a lullaby for Brent’s daughter Jessica. In fact, he brought her out to sit next to him when I saw them play it at the Garden the previous fall. It seemed out of place at the time, but you could once again hear the pain in Brent’s vocals. He held the final “Will” in the songs title for almost thirty seconds.

“I Need A Miracle” was never intended to become the inspiration for Deadheads’ pleas for an extra ticket. Its bluesy riff starts with an uncharacteristically raunchy guitar run from Jerry. It proved to be the perfect follow-up and when Bobby and the crowd sang “I Need A Miracle” before the crowd screamed back the “every day,” it felt like a full-on celebration. At this point, it seemed like the band would finish with a few strong songs from their more recent catalog.

That’s when Jerry began leading them back into “Dark Star” again. Holy shit. The recognition that we were all going back inside this most magical of spaces brought the house down again. They didn’t skimp on the second half either. The solo was fully developed even if it only a few minutes long. They made every note count. When Jerry finished the song with the second verse I couldn’t imagine what they could follow with.

As soon as they started “Attics of My Life” it was clear they were making sure we knew how special this night was. It easy to see why the band never really tried to play the song live. The harmonies are really tricky and the high notes always seemed way out of reach for the Dead. However, when they reached the peak of “When I had no wings to fly, you flew to me,” they’d left the crowd beyond blissful. As the rapturous applause engulfed the arena, Jerry began noodling with the “Playin’ in The Band” theme. The entire set really was one long song, although it was no unclear which one it was. They hadn’t ended a show like this in ages and Jerry was tearing into the finale as the band joined in to finish the song and the set.

They came back for the encore without the drummers and only Jerry held an instrument. They stepped to the microphones and began with “Lay down my dear brothers” as the crowd once again exploded. “And We Bid You Goodnight” was the only song they could really play at that point and it was perfect. Phil had his hands on his hips, Bobby in his pockets, and Jerry lightly strummed The Wolf. When they sang the last verse, Phil blew double kisses like an opera singer as Bobby put both hands up as if to surrender. Jerry waved to the crowd as they left the stage.

I turned to my girlfriend and said this was the one night I don’t think they could have done anything to make it better. Deep down I also knew this was the last time we’d see the Dead together. We broke up a month later. By March of the next year, I’d really start earning my Deadhead stripes when I hit nine shows in four cities. Spring 1990 is the only tour, along with the legendary Europe ’72 trek, to have every note officially released. Still, nothing quite measured up to 10/16/89. I did end up rushing that fraternity the same spring. I still remember when another brother played me the soundboard of the final Meadowlands show. He had gotten it from the WBAI 99.5 “Morning Dew” show that aired full Dead sets in the middle of the night. The show was just as good as I remembered it, although I spliced the audience reaction to the “Dark Star” when I copied it for myself.

After Adam Katz’ death, the Dead would never play the arena again, only Giants Stadium. For the spring tours, they even had to go back to playing Nassau Coliseum. A few months later, another Deadhead named Patrick Shanahan would die in police custody at a show at the LA Forum. The crowds at shows grew and grew. I saw more people than ever jump to the floor when they played “Shakedown” at Foxboro that summer. Brent sounded great, but was interjecting angry curses into his songs and was clearly hurting. No matter how much love he got from the crowd, it seemed like he could never make himself happy. He died of a “speedball” of morphine and cocaine three days after the tour ended. For some Deadheads, it represented the end of the band’s last great era. Jerry certainly never got over the death of Brent. Subsequent books and documentaries suggest that he took more solace than ever in heroin. My final show was a few stops from the end at the infamous 1995 performance at Deer Creek where gate crashers tore through the back fence. More riots and tear gas ensued. They cancelled the scheduled second show and Jerry would be dead the following month.

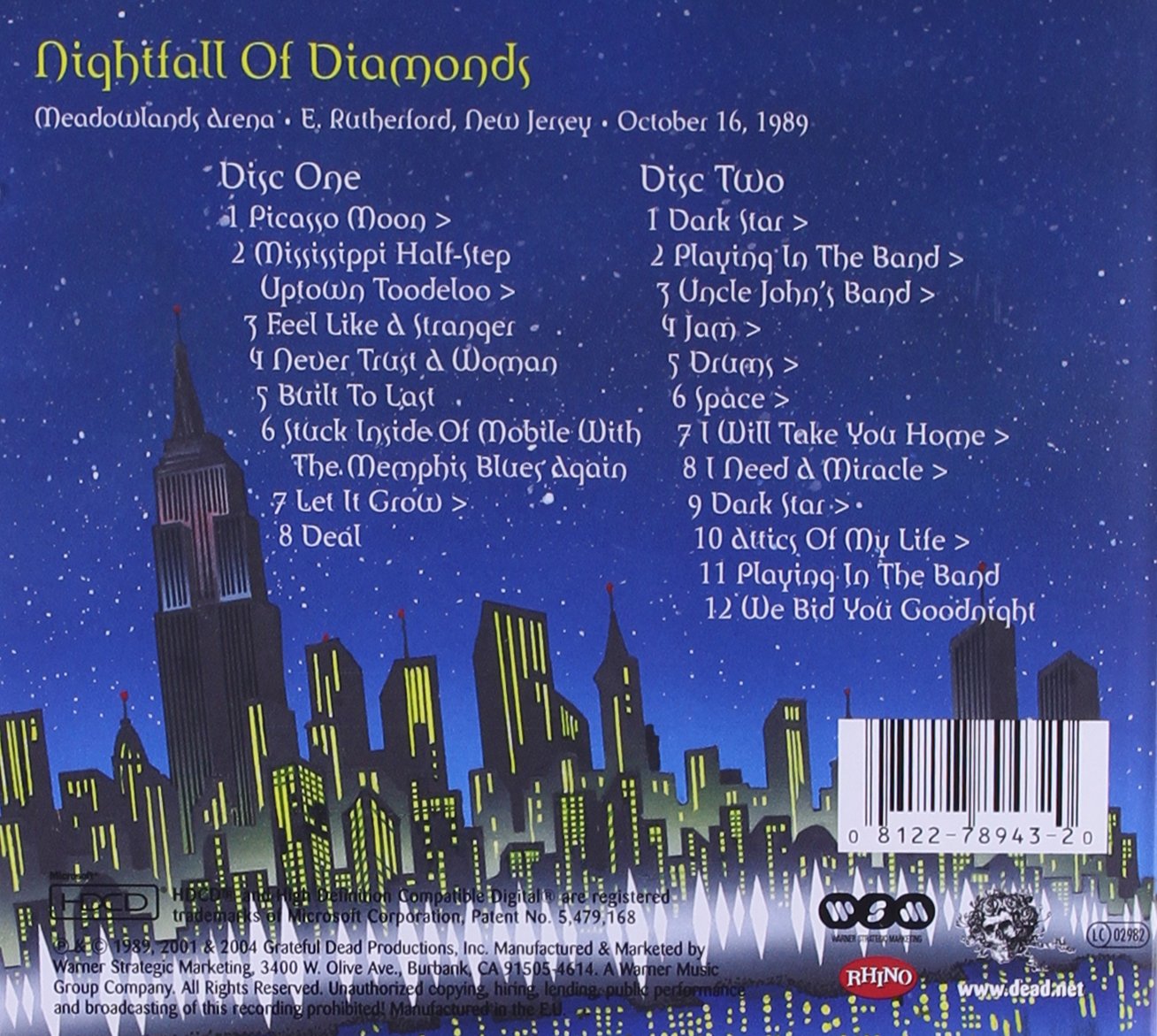

Built to Last, released on Halloween 1989, ended up being the Dead’s final studio release. The entire show from 10/16/89 was released in December 2001. The live album was entitled “Nightfall of Diamonds” after the song we’d all come to hear that night. It was fittingly dedicated to Adam Katz and the cover art prominently featured the Twin Towers to really make it feel like a tribute. A cruise ship, presumably the Circle Line leaves a trail of diamonds in its wake, between New York and New Jersey. The show has no verbal description in the liner notes, which allows the music to speak for itself. But no one in the building that night could forget what they saw or heard.

I saw many other great shows (with and without “Dark Star,”) most of which have been made into other live albums. But this night will always be at the top. I am far from the only one who attended who feels that way. I can still proudly say that when you Google “Meadowlands Arena—October 16, 1989” one of the first images that appears is my avatar on the Dead’s official site. The comment is now over twelve years old, but is as true as it was when I wrote it:

The best performance I have seen by any band, any place, period.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!