In an effort to address the ongoing defensive issues exhibited by the Penguins this season, I thought it might be helpful to take a step back from personnel discussions to take a broader look at the Penguins systematic approach to playing defense. In looking at their structure on paper and diagramming some video of their approach, we can hopefully ascertain a bit of what has plagued the Penguins in their own zone so far this season.

Let’s start with some context. Exactly where do the Penguins sit in the grand scheme of the league when it comes to defensive play? Let’s take a look at the numbers. Remember, this cumulative set of data is even-strength only:

Shot-Attempts Against Per 60: 23rd

Shots Against Per 60: 24th

Expected Goals Against Per 60: 25th

Scoring-Chances Against Per 60: 25th

This is a far cry from where the Penguins landed in these data buckets at the end of last season. Although they didn’t sit atop the league in these various categories, they certainly weren’t in the bottom third. While the Penguins are in a league of their own offensively speaking this season, they sit in the basement of the NHL in virtually every defensive metric.

The Penguins are getting league average goaltending right now, and thank goodness for that. If their goaltending was even slightly less than average (or their offense less potent) the Metropolitan division standings might look a lot different today.

With all that in mind, let’s take a look at what makes the Penguins tick defensively.

“I think that’s when our team is at its best, when our puck-possession is diligent. But also, when we don’t have it, we pursue it pretty hard and cooperatively as a group. I think we’re difficult to play against, we can suffocate teams by taking time and space away all over the rink and making them fight for every inch. We have strategies so that we can work together to try and make that happen.” – Mike Sullivan

So what are those strategies, exactly? Specific to the defensive zone, the Penguins employ a Strong-Side Overload, also known as a Half-Ice Overload.

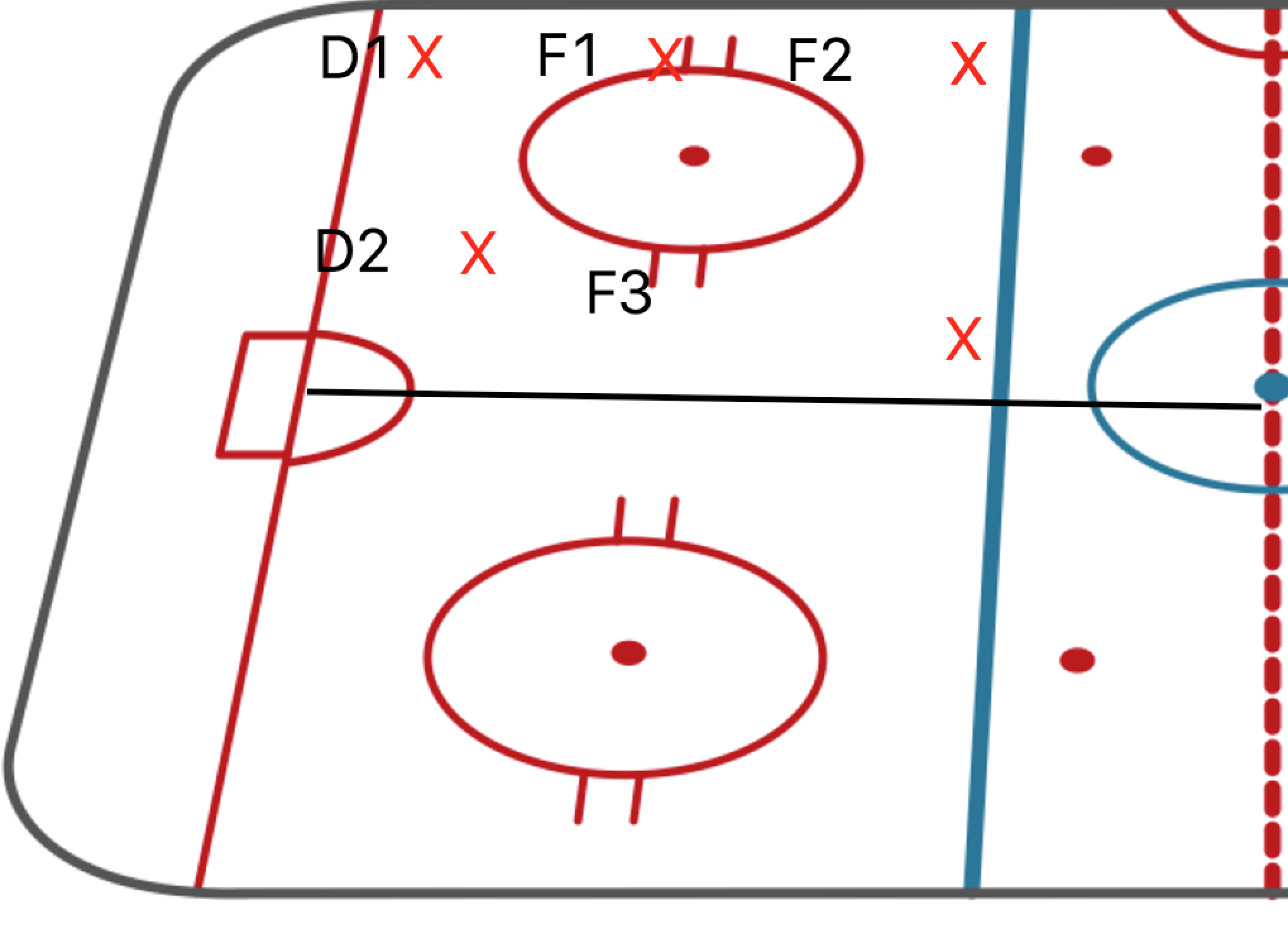

Here’s how the Penguins defense looks on paper:

This system is a perfect fit for the Penguins roster and an aggressive coach like Mike Sullivan.

In the Overload structure, the entire idea is to consistently put your team in a position where it has more bodies in puck battles than the opposition does.

To accomplish this goal, the defending team splits the ice surface in half. When the puck heads in the near wall, the overload shifts to the near wall. If the puck heads back to the far wall, the overload shifts to the far wall. The focus is primarily placed on the side of the ice where the puck is located.

There are several variations of this system that place different players in different positions, but I believe the diagram above succinctly lays out the approach the Penguins take. As Mike Sullivan indicated in his quote at the top of this section, the idea here is to use the inherent speed on the roster to take time and space away from the opposition and flood the area the puck is located with sticks and bodies.

If you take a look at the digram, the red X’s indicate the position of cycling offensive opponents. No matter who the puck carrier is in a given situation, the Penguins are in a position to put a mass of bodies on the puck-carrier to force turnovers.

This defensive structure also lends itself to quick breakouts. When a turnover is forced from this defensive posture, there’s typically one or two players in alignment with each other to touch-pass their way out of the offensive zone, which we’ll get to see in a moment.

The issues that arise from this defensive structure are generally prevalent when you encounter a team that is deceptive and accurate with moving the puck in traffic. Whichever player finds himself in the position of F3 has a daunting task in front of them. They need to be aware of bodies floating into the slot and sneaking into the play from the backside. Remember what we said above, the idea behind this system is to divide the defensive zone in half. It stands to reason, then, that the other half of the ice would be completely wide open. This is often the case, and its the job of the F3 to serve as a bit of a “lighthouse” in this system. They need to be aware of all hazards that exist at every open area around them.

Let’s take a look at this system in action:

Here’s a quick GIF of a zone entry from the Boston Bruins last week. Take a look at how the Penguins flood the wall after Matt Murray deflects a long shot into the corner.

The Penguins overload the puck side along the wall. Every time a Bruins forward steps into a puck battle, the Penguins have an extra body in the mix to outnumber the Bruins and swarm to the location of the puck.

In this instance, take a close look at Carl Hagelin. He plays the role of the F3 here. He’s in position to cut this play off should the puck continue around the net and the play switch to the far side of the ice. He’s also the lone man in the slot, tasked with maintaining the center of the ice.

Also notice how fluid this is. Because Brian Dumoulin stepped up on the puck carrier earlier, he’s way behind the play in this sequence and it takes him a moment to catch up. Nick Bonino plays the role of D1 on this coverage until Dumoulin is able to get back into the play. This is a plug and play strategy that the Penguins generally excel at sans a few hiccups, which we’ll also look at later.

Here’s another great clip of this system in action. In this sequence, the Bruins flip the play from one side of the ice to the other. You get a real great sense of how tenacious the Penguins are in shifting their overload to shadow and match the Bruins. It’s also an excellent example of how this system divides the ice in half:

In this instance, we can see the Penguins in their standard Strong-Side Overload structure. However, the play quickly switches from one side of the ice to the other. The Penguins have to react quickly and completely switch to the near boards.

Take a look at the swarm of white jerseys around the puck here. Every Bruins forward has two or three Penguins to contend with in order to make a clean play on the puck.

In this sequence, Brian Rust and Conor Sheary swap duties as the all-important F3. With the puck on the far wall, Rust sits in the slot to monitor the center of the ice. As this play switches back to the near boards, Rust abandons post to pressure the puck, and Sheary seamlessly slides into the slot to take over.

Here’s one final look at this system in action recently:

Once again, pay close attention to Conor Sheary’s poke-check as the all important F3 in this structure. His job is to have his head on a swivel and prevent the Bruins from gaining access to center. His poke check breaks this play up and the Penguins head off to the races with good numbers.

At their best strength, the Bruins spend most of these sequences outnumbered by at least one player. While this is a high-intensity system that requires a lot of skating and cognizance among players, the Penguins have the roster to pull it off.

Of course, it isn’t always this flawless. Let’s take a look at an instance from the Penguins 8-7 circus-like victory over the Capitals for an example:

In this sequence, the Penguins go into their standard overload posture, but the F3 is notoriously absent from the side of the net/slot area. there’s a gaping hole in the Penguins coverage here. Signals get crossed, and the Penguins have one forward who is completely out of position here.

So, after all this analysis, the question remains: is this system primarily responsible for the Penguins porous defense?

Well, I don’t personally think we can attribute all the Penguins woes to this specific system. Let’s consider the following points.

When the Penguins are in position when other teams have distinct control of the puck in their defensive zone, they’re extremely hard to play against and they effectively take away time and space.

However, they’ve become a subject to what Mike Sullivan calls the “hope” play. In short, once the Penguins gain possession of the puck, they’ve become a little too prone to just opting for a blind bank off the boards or a chip to an open area where a teammate may or may not be. For me, that’s not a product of the system, that’s just a product of not making a good heads up play.

In the above instance from the Capitals game, Phil Kessel also abandons ship defensively to try and get a head start on the breakout. In watching video, there’s a bit of a discipline discussion to be had here. Sometimes the Penguins get a little antsy in wanting to head up ice and are prone to jumping out of position when they believe a teammate has won a puck battle that isn’t over yet. This isn’t symptomatic of the system itself, but does put a glaring hole in a Penguins system that is reliant on outmanning the competition and carefully watching the center of the ice.

Also, let’s remember that the Penguins take a ton of chances by pinching their defense into the play. When teams create odd man rushes against them, they never have the opportunity to properly set up in this overload. I believe that their scoring chance numbers are directly a reflection of the odd-man rushes they allow and not this system specifically.

As I mentioned above, things aren’t always perfect. The Penguins do have a tendency to lose someone in the slot, or to lose a puck battle where they have a two-on-one advantage, but overall, I don’t see this defensive posture as being a primary pain point for them from a defensive standpoint.

Add The Sports Daily to your Google News Feed!